Old Version

Old Version

Pyramid Schemes

Police detain alleged scammers in Xi’an city, Shaanxi Province, August 11, 2017

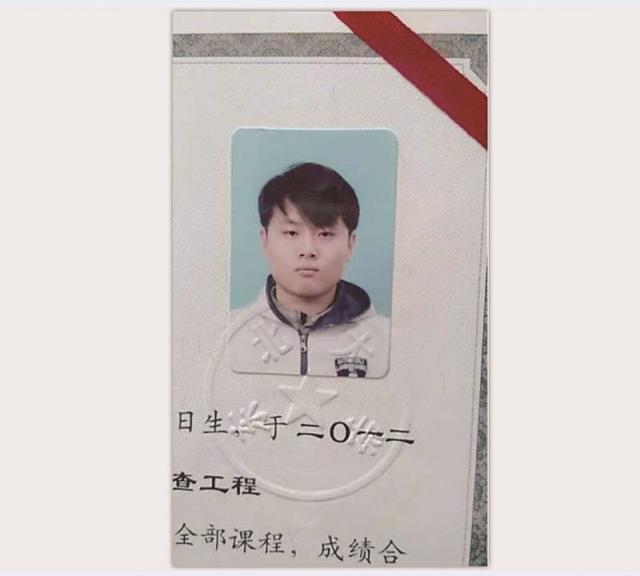

Li Wenxing, victim of a pyramid scheme

The recent death of Li Wenxing, a 23-year-old college graduate who fell victim to a pyramid scheme, has made national headlines and sparked widespread anger over the spread of such schemes throughout the country.

Li was found dead on July 14 in a small pond by a highway on the outskirts of Tianjin, a city not far from Beijing. Initial investigations showed that the engineering graduate had traveled to the city after receiving a job offer via Boss Zhipin, a popular online recruitment platform. He is believed to are believed have been illegally detained by a pyramid scam gang.

Li is one of several young people who have died at the hands of such gangs in recent weeks. Three weeks later, on August 4, Lin Huarong, a sophomore student from Hunan, was drowned following a scuffle with a pyramid scheme gang who had held her captive for several days. Like Li, Lin told family members that she had been offered a summer job.

Following public scrutiny of the events, local police have begun to act. In raids following Li’s death, Tianjin police announced that they had arrested seven top-level leaders and 25 senior organizers of the pyramid scheme. The police estimate the scheme has recruited more than 1,600 people in the vicinity of Tianjin, and 7,000 members across China. Regarding Lin’s case, local police detained five suspects in relation to her death.

Yet raids like those in Tianjin are nothing new. According to the Ministry of Public Security, in the first half of 2016 alone, the police busted 933 pyramid schemes, involving total funds of 4.15 billion yuan (US$622 million). In total, 1,210 suspects were arrested during this period. Despite the crackdown, the problem appears to be getting more serious.

Pyramid schemes first emerged in the 1980s, not long after Western direct sales companies such as Amway and Sunrider had started to operate in the country. This business model seemed novel in a society that had experienced several decades of a planned economy. The unique pay structure and commissions meant that this new format boomed. However, some direct sales projects soon transformed into pyramid schemes, characterized by token products, with a primary focus on selling fraudulent “investments.”

With the rapid spread of these pyramid schemes, the Chinese government banned all direct sales companies in 1998. Then in 2005 as part of its commitment to entering the World Trade Organization, it released a decree that officially distinguished direct sales from pyramid schemes, albeit with the distinction that sales agents could not directly recruit other agents or take royalties from other sellers. Nevertheless, direct sales schemes were re-legalized.

Bolstering the anti-pyramid scheme legislation in 2009, China’s criminal law was amended to make operating such schemes a distinct criminal offense.

Despite the legislative changes, pyramid schemes have continued to flourish in many areas. A key factor in their continued prevalence is the rise of Internet use in China. Unlike in the 1990s when pyramid scheme gangs relied on face-to-face contact to recruit members, online networks now mean that they are able to reach their potential victims more effectively, anonymously and with much greater geographical reach – all factors that hinder the police in their work countering these schemes.

In the case of Li Wenxing, criticism has focused on the recruitment website Boss

Zhipin, a fast-growing start-up with more than 10 million users, for failing to verify ads posted by the pyramid scam gang. Under media scrutiny in the wake of Li’s death, it has been reported that similar problems exist in all of China’s major online job-seeking platforms.

Preying on college students, recent graduates and young rural-to-urban migrants who come to cities in search of jobs, pyramid scheme gangs often lure the victims to their “offices” with the promise of high-paid jobs.

Once the job-seekers arrive, the gangs typically confiscate mobile phones, ID documents, cash and bank cards. These victims are then followed around the clock and are subject to “training” and preaching of the project’s “prosperous” future. During the process, victims are put under duress to “invest” in the project, or to borrow money from their family and friends if they have insufficient money themselves to do so.

In the wake of the deaths of Li, Lin and others like them, the authorities have increased efforts to crack down on pyramid schemes. On August 14, the Ministry of Public Security, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security and the State Administration for Industry and Commerce, released a joint decree, launching a coordinated three-month campaign against such schemes.

By coordinating efforts across government departments, the campaign is targeting specific schemes that focus on job-seeking platforms and young students and migrants. However, given the complexity of these schemes, the impact of campaigns like this may be limited.

Unlike the schemes that rely on physical coercion which is clearly illegal, many pyramid schemes are now disguised as investment schemes or Ponzi schemes where the company being invested in has been fabricated. These are perhaps less obvious to ordinary people, while also being harder for the police to crack down on.

Taking advantage of China’s increasingly complex financial markets and the lack of financial knowledge among many ordinary people, such schemes promise high returns to tempt victims to invest. In many cases, these pyramid schemes also bear the characteristics of a Ponzi scheme, relying on recruiting new investors to pay off yields to existing investors.

Last year, police busted Ezubao, a peer-to-peer lending company, whose 30 leaders cheated 900,000 investors out of more than 50 billion yuan (US$7.4 billion) in just 18 months. In April this year, police in Guangzhou announced they had shut down several online pyramid schemes covering 10 provinces and involving over 4 billion yuan (US$600 million), with 430 suspects detained as a result. According to the police, one of the online schemes, Renren Gongyi (Everyone’s Charity) alone attracted 1 billion yuan (US$150 million) in investment in just a month.

On July 22, the Ministry of Public Security announced that it had shattered another pyramid scheme called Shanxinhui (Kindness Exchange). Established in 2013, the company promoted the concept of “helping the poor and sharing the wealth” and has made major donations to various charity funds. In the meantime, it sold “benevolence credits” to members, while offering monthly interest of 10 to 30 percent on the “charity investments” they made. According to the authorities, by the time the scheme was shut down, it already had five million members, who had invested tens of billions of Chinese yuan in the scheme.

In a surreal twist, following the scheme’s closure, hundreds of Shanxinhui’s members, concerned that their investment may be forever lost, took to the streets of Beijing, drawing the attention of international media. They urged the government to release the scheme’s leader, Zhang Tianming, and to allow the company to resume operations. As a result, 63 protesters were detained, with the authorities vowing that they would strengthen their crackdown on fraudulent financial schemes to prevent financial crises and to safeguard social stability.

In order to effectively eradicate pyramid schemes, some experts say the government may need to re-examine its approach to financial regulation.

According to a report released by the Institute of Capital and Finance (ICF) under the Chinese University of Political Science and Law, a major reason behind the emergence of fraudulent investment products is the government’s promotion of “internet finance” in recent years.

In an interview with the Legal Daily, Wu Changhai, head of the research center of the Internet Economy (part of the ICF) said that in their effort to promote financial innovation, the authorities have developed a rather passive attitude towards the regulation and supervision of emerging online financial markets, which has contributed to the spread of fraudulent investments.

Wu warns that without effective legislation and regulation of internet finance, not only is there no way fraudulent investment projects can be effectively curbed online, but there is a risk they will undermine social and financial stability.