While Peking opera fans in China have shriveled in number over the past few decades, the art form has received a warm reception in foreign countries like Germany, giving experts hope the tradition can be revived on the domestic stage

Bolstering trade and clearing the country’s skies were not the only items on the agenda of this year’s Two Sessions, the annual meetings of China’s top legislature and highest political advisory body. Also on the list, amongst others, was Peking opera.

As China establishes closer relations with other international players, cultural exchanges, especially those steeped in tradition, have become a hot topic at the yearly conferences.

During the March sessions held in Beijing, renowned Peking opera performers Mei Baojiu and Yang Chi, who spoke at the meetings, once again voiced concerns about the development of Peking opera, warning that the traditional art form is suffering a decline in interest in China, despite signs of popularity overseas.

Wu Xingtang, former second secretary of the cultural section of the Chinese embassy in Germany, recently wrote an article for News- China’s Chinese edition about a Peking opera troupe’s 1981 debut in Germany, exploring how and why the traditional Chinese opera was so well received in a Western country. The disparity between reactions at home and abroad may indicate that Peking opera can still charm new audiences in the modern era and deserves to be passed on to future generations, something many Chinese nationals hope will come to pass.

‘Exporting’ Culture A cultural icon that occupies a spot on UNESCO’s “intangible cultural heritage” list, Peking opera first arrived on a foreign stage in 1891, when then well-known Peking opera performer Zhang Guixuan introduced the art form to Japan. It later took its place in the global arts world when famous Peking opera artist Mei Lanfang went on a global tour in the 1920s and ’30s. This kind of cultural exchange, however, practically stopped altogether as the world descended into war.

According to Wu Xingtang, the new Chinese government that was created in 1949 did not “export” any traditional Chinese culture to Western countries until it established diplomatic relations with them in the 1970s. Frequent cultural exchanges with Germany specifically began in 1979, the year that China became more accessible under its new policy of Reform and Opening-up. When the World Theater Festival (Theater der Welt) first launched in 1981 in Germany’s Cologne, China sent a Peking opera troupe to attend, with Wu serving as one of the trip organizers.

“A German friend of mine recommended we go to the opera festival, which companies from many European countries, the birthplaces of the world’s classic and modern operas, would attend,” Wu wrote.

“As many European people seemed to enjoy traditional Chinese culture, we believed that it would be a good chance to promote Peking opera overseas.” Based on a 1979 agreement signed by China’s Ministry of Culture and Germany’s foreign ministry, Peking opera was set to be launched in Germany as a commercial endeavor, with the Chinese side footing the bill for the performers’ plane tickets and daily expenses and the Germans bearing all other costs.

Besides the theater festival, the Germans also planned a 14-day tour in seven cities to boost ticket sales, a schedule so tight that it scared off two of the three Peking opera troupes that had intended to join.

When the Chinese side finally settled their list of performers and programs after rounds of discussions, it was too late to book a Cologne theater. Thus, Peking opera’s first official performance in Germany took place at the city’s local stadium.

In April 1981, the China National Peking Opera Company, the last company standing, sent three members to Germany to prepare for the coming tour. They brought photos of Peking opera performances with them to use for marketing purposes. Although the pictures were grainy because of China’s lack of high-quality cameras at the time, the German side transformed them into eye-catching posters, printed with a simple slogan: “Here comes the Peking opera!” Wu originally worried that the slogan was too plain to attract an audience, but his German counterparts assured him that simplicity was the way to go. Sure enough, every performance during the Chinese

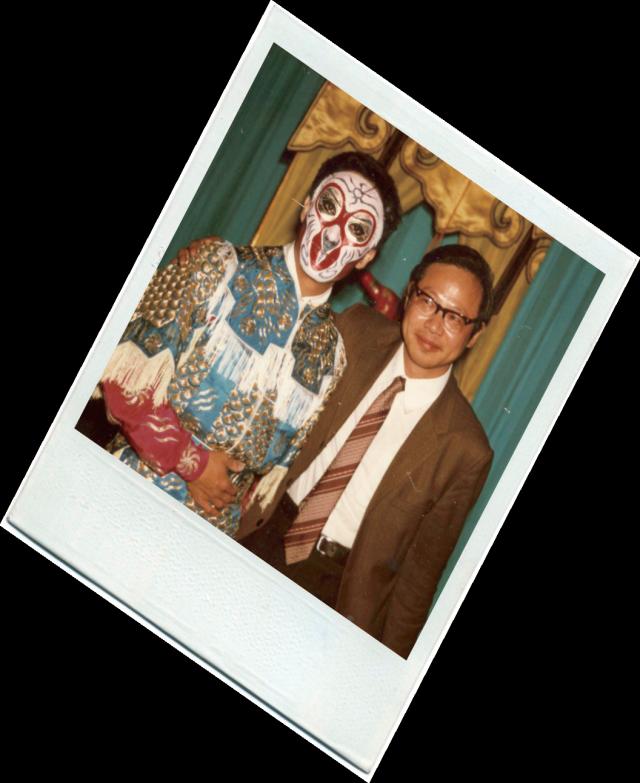

Li Baochun (left) wears a costume representing the Chinese folk hero Monkey King

troupe’s three-day stint in Cologne was sold out. Crowds filled the 2,700-seat stadium every night.

Show Time Wu said the Peking opera troupe prepared three different programs packed with selected scenes from both martial and domestic operas.

(Martial operas typically depict powerful emperors and wise officials fighting off treacherous foes, while their c o u n t e r p a r t s concentrate on romance, family drama and even the spiritual realm.) Interestingly, the stadium, chosen as a last resort, ended up contributing to the performances’ lively atmosphere by making audience members feel free to cheer and applaud at will instead of waiting for the austere fall of a curtain. The performance was so in demand that hundreds of latecomers crowded around the gate inquiring about extra tickets.

Although the German organizers did not want to let them in, Wu revealed that he surreptitiously opened a side door and allowed some people to watch from backstage.

This Peking opera fervor continued throughout the seven-city tour, even in the smaller cities, like Lower Saxony’s Hildesheim. The director of Hildesheim’s local theater told Wu that the show’s tickets sold out rapidly and the theater had to add temporary seats to accommodate more audience members. Even the mayor told Wu that he would like to help finance the performance.

Unlike the crowd in Cologne, most of the theatergoers in Hildesheim were older and took opera very seriously. They dressed formally, the men in dark suits and the women bedecked with jewels, just as they did when attending classic European operas. At the end of the night, the performers basked in repeated curtain calls.

While touring in Böblingen, a town neighboring Stuttgart, the home of Mercedes-Benz headquarters, the luxury car company invited the Chinese opera troupe to visit its factory base. Mercedes-Benz also quietly sponsored the group’s Böblingen performance, keeping its name off of the posters and other promotional materials.

According to Wu, many German enterprises consider supporting cultural activities part of their company culture.

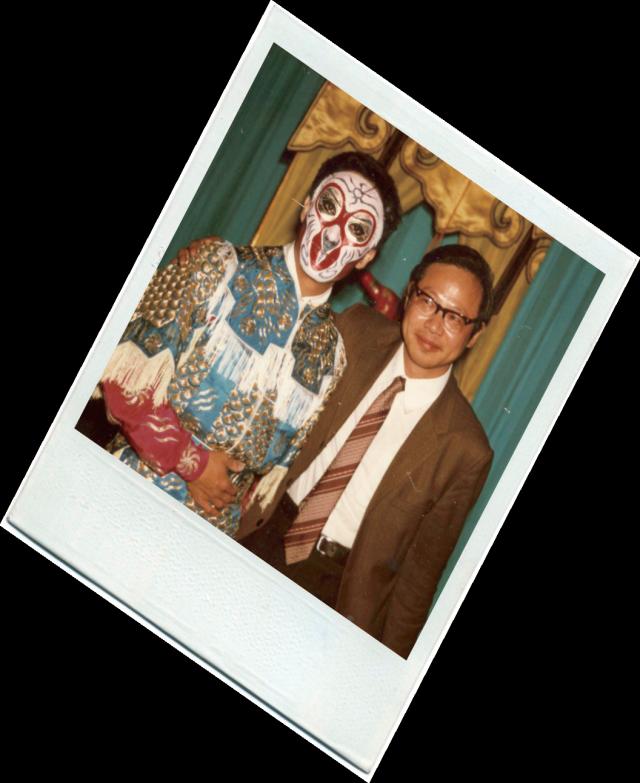

Same Tune One of the scenes the troupe performed was from Farewell My Concubine, a classic story that later became part of the famous novel and film of the same name. The opera takes place after the fall of the Qin Dynasty (221-207 BC), when the warlord Xiang Yu suffered a debilitating defeat at the hands of his enemy Liu Bang, and it ends with his favorite concubine cutting her own throat in front of him. The actor who portrayed Xiang Yu, Yuan Shihai, recalled audience members’ enthusiasm for the shows throughout the 14-day circuit. After each performance, viewers and journalists always swarmed him, even before he could take off his costume and remove his make-up. He took advantage of these moments to ask many Germans about their thoughts on Peking opera.

“Some audience members said that they liked martial plays a lot,

Group photo with Yuan Shihai (farthest right), who played the male lead in scenes from the opera Farewell My Concubine

because of the excitement and remarkable kung fu, but more said that they were moved by the singing, since it was similar to [that of European] operas,” Yuan said. “A person from a Sino-German cultural association told me that Farewell My Concubine was one of his favorites. The historical Chinese story includes a hero and a beauty, along with marvelous singing and beautiful dancing. These [aspects] are what attract people to European operas.” The Chinese troupe added translated subtitles and a brief introduction of the lead roles in each of the performances to make the show more accessible to German audiences.

“Similar to Western opera, Peking opera should be appreciated with ears and hearts,” Yuan said. “I was very happy to hear that some German patrons were interested in watching Peking operas in their entirety [rather than just selected highlights from different shows].” Passing it Down The idea that Peking opera could act as an ambassador for Chinese culture existed well before this German trip, however. In fact, during a 1935 tour of the Soviet Union, Mei Lanfang, one of the most famous opera performers of the 20th century, stated that “the barriers between Peking and foreign operas could be broken.” Former Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai supported this sentiment. Yuan Shihai revealed that Zhou once met with him and two other Peking opera performers in 1974, hoping to devise a way for Peking opera to test the waters abroad. “Don’t worry about foreigners not understanding Peking opera,” Yuan recalled Zhou saying. “It is just like European opera.” According to Yuan, their 1981 performances in Germany were actually a trial run as China looked into exporting Peking opera for the first time in decades. It was an undeniable success. In the following decades, Peking opera gained mounting popularity overseas, with many Peking opera associations or clubs popping up in Germany, the US, the Netherlands and more. Seemingly every time China sent Peking opera troupes overseas, local media reported packed theaters and shows ending to thunderous applause. In June 2013, for example, several thousand Germans gathered in an open square in the small town of Dietfurt to watch the Nanjing Peking Opera Troupe, even though it was a rainy day. More recently, a lecture in Frankfurt given by Yang Chi, a Peking opera performer and apprentice of Yuan Shihai, attracted several hundred locals.

In sharp contrast, enthusiasm for Peking opera has dwindled domestically, much like Western operas in their home countries. Members of the opera world like Yang Chi have attributed this to “a lack of new audiences” and “a lack of new elements to attract more market share.” Experts believe that unlike foreign audiences, who feel like everything Chinese is fresh and exotic, youth in China are all too familiar with the ancient stories portrayed on operatic stages and find the performances boring and outdated.

Master performers Mei Baojiu and Yang Chi said they believe this can be fixed through education and promotion. That is why both opera legends advocated bringing Peking opera into elementary and middle schools.

“Peking opera reached new heights after the Cultural Revolution [1966-1976] because there were still many people interested in traditional operas. However, it began to decline starting in the 1990s, when the Reform and Opening-up policy flooded China with more and more forms of entertainment,” Song Yan, head of Fenglei Peking Opera Troupe, told Sanlian Lifeweek magazine. “As people are turning to modern entertainment, Peking opera still idles on the government dime and has no clear idea of how to reform.” In a 2014 interview with the magazine Shanghai Artist, German opera composer Karsten Gundermann, who also collaborates on traditional Chinese operas, said that Western operas have not been immune to these same modern-day ailments, but he was confident that both Peking and Western operas can enchant audiences once again by reinventing performance methods.

“In the modern era, we have to learn to promote traditional operas in new, modern ways, such as creating new stories [and] building new stars,” he said.

China is already making an effort in this regard. In March 2014, for example, China’s National Center for the Performing Arts debuted a filmed rendition of the China-set Italian opera Turandot in movie theaters and received a satisfactory box office take. Reinventing the opera like this may be helpful in passing down the tradition to future generations.

As Gundermann said, in citing an old German saying: “We should pass on the fire of traditional culture, rather than the ashes.” Wu Xingtang contributed to this story.

Old Version

Old Version