On November 7, 2017, China’s National People’s Congress (NPC), the country’s top legislature, published a draft national supervision law, which was made available for public comment until December 6, 2017.

The draft law was released after China’s leadership announced during the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) held in mid-October that a national supervisory system would be set up by the end of 2017 or in early 2018, which will oversee all State organs and civil servants. The system will include supervisory commissions to be established at provincial, city and county- levels across the country to ensure that “all public servants exercising public power” are subject to supervision.

The plan to establish a national supervisory system by incorporating all existing anti-corruption authorities and functions to create an integrated super-supervision agency was first raised in November 2016 by the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI). Under the reform plan, a new and separate “supervision branch” will be created out of China’s existing governance structure.

The new supervision committee will not be made subject to the administrative branch of the government, the State Council, nor will it be subject to the judicial branch, the Supreme People’s Court or the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, China’s public prosecutor. Instead, the national supervision committee, with its local branches, will be independent from the administrative and judicial branches of the government and be parallel to them in terms of legal status.

Pilot Programs

The NPC announced a pilot program in December 2016 for the supervisory system reform to be conducted in Beijing, and in Shanxi and Zhejiang provinces.

By the end of April 2017, supervisory commissions were established at the provincial, city and county-level throughout Shanxi, Beijing and Zhejiang. In Shanxi Province, 1,884 staff and officials from existing anti-corruption authorities were transferred to the new agency, accounting for 85 percent of the total 2,224 positions designated for the agency.

Under the pilot program in Shanxi, the new supervision commissions dealt with 2,156 cases, leading to the administrative disciplining of 1,887 individuals. Five individuals were handed over to judicial authorities under criminal charges.

A common approach in all three localities is that the supervision commissions at the provincial and municipal levels are divided into “discipline supervision” offices and “discipline inspection” offices. Under the pilot program, supervision offices are responsible for routine discipline supervision, while the inspection offices are responsible for handling reports and tip-offs.

In Shanxi Province, for example, there are 10 offices within the provincial supervision commission, with eight supervision offices and two inspection offices. In Zhejiang Province, the provincial supervision commission has seven supervision offices and six inspection offices. In Beijing, there are eight supervision offices and eight inspection offices under the municipal supervision commission, as well as another office responsible for recovering corruption-related funds and pursuing officials suspected of corruption that have fled abroad.

A major goal of the reform is to extend the scope of the existing scattered supervision authorities to everyone in the public sector who holds public powers. According to official data, with the establishment of the supervision commission, the number of people under supervision rose from 210,000 to 997,000 in Beijing, from 785,000 to 1.3 million in Shanxi, and from 383,000 to 701,000 in Zhejiang.

‘Liuzhi’ vs ‘Shuanggui’

Under the draft national supervision law, the supervision commission is authorized by the NPC to have multiple means to perform its designated duties, including residential surveillance, freezing of property and detention. The most watched measure among them is the introduction of a new detention system called liuzhi, which will replace the current controversial shuanggui system.

Shuanggui, literally meaning “to answer questions at a designated time and place,” is an intra-Party disciplinary practice applicable to CPC members under a Party regulation released in 1994. As there has been no clear definition of this practice, it often led to secret detention over extended periods without effective protection of personal rights. Even legal experts within the Party admit that this form of extrajudicial detention is problematic.

The draft national supervision law appears to address some of the problems. For example, it stipulates that family members of detainees must be informed within 24 hours of the detention, and the date and length of detention must be specified. The draft law also stipulates that investigators must ensure that detainees have access to food, water, rest and adequate medical services, and that the inquiry process must be videotaped. If the detainee is eventually sentenced, the term of detention under liuzhi should be offset against the penalty he/she receives.

By introducing a new liuzhi detention system under a new supervision law, the authorities aim to institutionalize the high-profile anti-corruption drives and legitimize the anti-graft mechanism, which has been a key signature of the Chinese leadership under President Xi Jinping. Referring to the new detention system, Xiao Pei, deputy secretary to the CCDI, said at a news conference following the 19th Party Congress that the authorities will in the future tackle corruption through “the rule of law.”

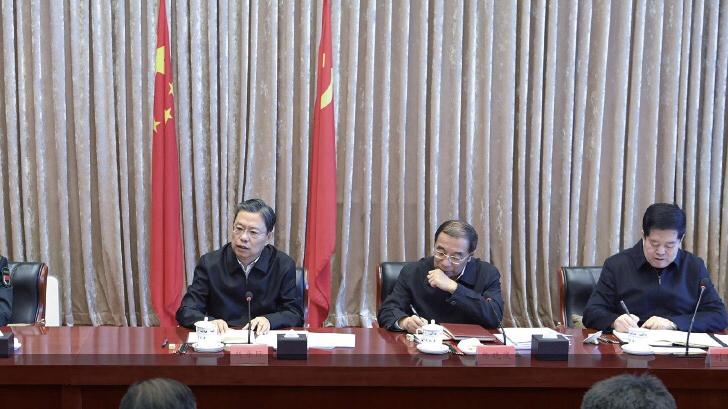

Along with establishing the supervision commission, the liuzhi practices are also included in the pilot programs. The Zhejiang authorities, for example, released a guideline on specific procedures on how to apply the detention system. Liu Jianchao, Secretary of the Zhejiang Provincial Commission for Discipline Inspection and director of the newly established provincial supervision commission, told NewsChina that 113 individuals have been detained under the new detention system in Zhejiang, and of these, more than 60 have been handed over to the judicial authorities.

Overlapping Functions

On October 29, the CCDI announced in its work report delivered to the 19th Party Congress that based on the existing pilot programs, a national supervision commission will be set up. According to the report, the new supervision commission will share responsibility, organization and facilities with the CCDI.

In the meantime, all provinces, regions and municipalities will establish their own supervision commissions at provincial, city and county-levels by the end of 2017 or in early 2018.

But despite the pilot programs, the emergence of a new supervisory branch of government still poses some legal and institutional challenges, especially regarding the relationship between the supervision commission and the judicial branch, which appears to share many overlapping functions, such as investigations and detention.

According to Huang Xiaowei, deputy Party secretary of Shanxi Province, the Party’s provincial political and legal commission has set up a special team to coordinate the functions between its newly established provincial supervision commission and existing law enforcement authorities, including the police, prosecutors and the courts.

Huang also said that the province has enacted regulations regarding how the prosecutors should cooperate with the supervision commission. Under the regulations, the procuratorate has the power to refuse to press charges against suspects if it deems a case cannot be substantiated, as well as procedures for the supervision commission to make appeals.

According to Liu, director of the Zhejiang provincial supervision commission, procedures like this will ensure that the relationship between the commission and the judicial authorities will be one of “cooperation and mutual supervision,” adding that this will look at how abuses of power can be avoided under the new system.

But with only limited cases under the pilot programs, the current discussion tends to be very abstract. As the new supervision system looks set to roll out over the following months, how these issues will be worked out under the ambitious reform remains to be seen.

Old Version

Old Version