China is adjusting its Belt and Road strategy amid escalating rivalry with the US, even as more European countries come aboard

In late April, China held the second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing, which was attended by some 6,000 delegates, including the leaders of 37 countries and diplomats and officials from 150 countries and 92 international organizations. At the end of the three-day event, China declared that it had resulted in 283 deliverables, along with a joint statement in which the participants agreed to push forward the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Launched in 2013, the BRI has become an iconic project of the Chinese leadership under President Xi Jinping, which aims to integrate the economies along the ancient Silk Road routes and promote trade and investment in the regions through infrastructure building.

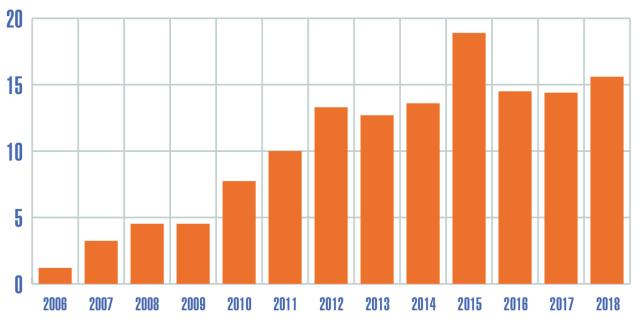

It is estimated that China has invested US$90 billion in projects in the past six years, and according to China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), China’s direct investment in BRI countries increased by 8.9 percent to reach US$15.64 billion in 2018, creating 842,000 jobs in host countries.

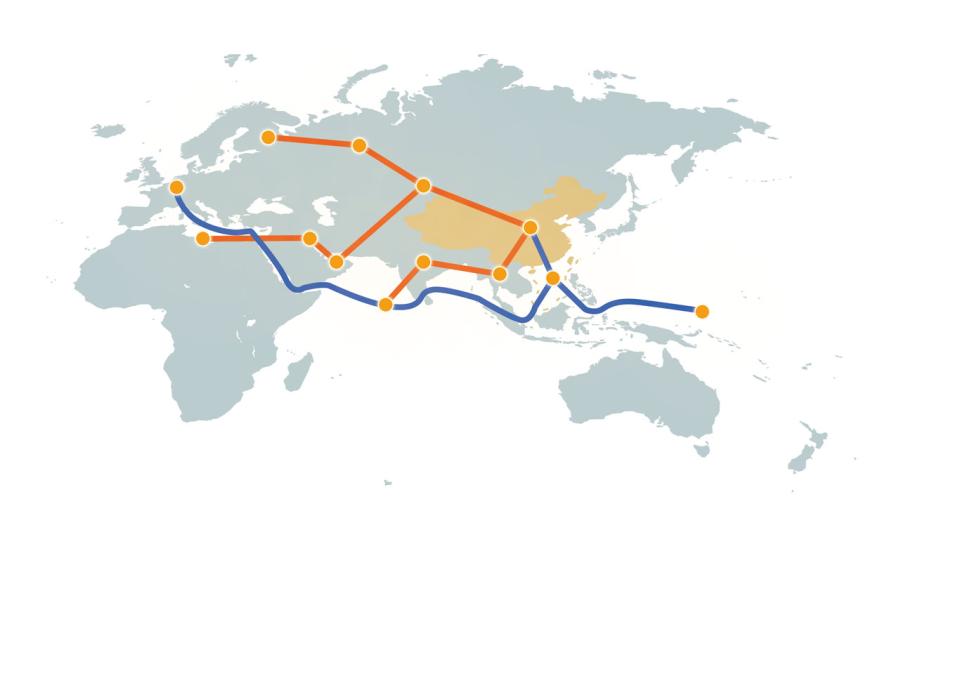

According to Chinese State media, in the past six years China has signed 123 cooperation documents on the BRI with 105 countries throughout Asia, Africa, Europe, Latin America, and the South Pacific, as well as 26 agreements with 29 international organizations.

Mounting Criticism

Despite these achievements, the BRI has met with increasingly strident backlash, mostly from Western governments which tend to view it as a means to spread Chinese political influence abroad, while trapping poor countries under unsustainable debt loads.

The rhetoric of the US government has been particularly hostile, especially compared with the tone around the first Belt and Road Forum held by China in 2017. Back then, the US government sent observers who adopted a rather conciliatory tone, saying the BRI has “much to offer” to the world.

But as the Trump administration has identified China as a major “strategic rival,” not only did Washington boycott the second Belt and Road Forum by refusing to send high-level officials, its rhetoric has taken a sharp turn.

During his trip to South America in April, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo lambasted China for “spreading disorder” in Latin America through failing investment that “injects corrosive capital into the economic bloodstream, giving life to corruption, and eroding good governance,” according to the US Department of State’s Twitter account.

In his visit to London in early May, Pompeo doubled down on his attack, slamming China for selling “corrupt infrastructure deals in exchange for political influence” and using “bribe-fueled debt-trap diplomacy,” Reuters reported.

According to ex-Trump advisor Steve Bannon, a known hawk, the Trump administration now considers the BRI as “the perfect manifestation of the Chinese Communist Party’s East India Company model of predatory capitalism.”

But for many non-Western analysts, the accusation that China is promoting debt-trap diplomacy and predatory capitalism is greatly exaggerated.

“The problem is that the West considers the BRI a threat and put it under the spotlight. If only a few projects experienced problems, these are quickly magnified and exaggerated,” said Li Mingjiang, an associate professor at S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University.

Li and many other experts believe the US’s opposition to the BRI stems more from a geopolitical point of view, especially when Washington itself has been seeking to adopt what many say a “disengagement” policy towards China, hardening its stance on a variety of issues including trade, technology, military and the Taiwan issue.

Debt Trap?

According to Gu Qingyang, associate Professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore, the argument that the BRI is a “debt trap” stems from the discrepancy between China and other countries’ understanding of the nature of infrastructure projects. Gu told NewsChina that infrastructure projects such as roads, railways and ports are mostly public goods, which themselves are prone to market failure but can benefit the country’s overall economy.

“China’s own economic development in the past four decades was achieved through making massive State-led investments in infrastructure projects that are often unprofitable,” Gu said. “If one only applies a narrowly defined cost-benefit analysis, many of these BRI projects themselves may not be profitable.”

Gu argued that despite insolvency problems in some BRI projects, China should be given more credit for the wider economic and social benefits resulting from its overall infrastructure investment in both the BRI region and the whole world. Gu’s argument appears to be backed by various studies. For example, a study led by Michele Ruta, an economist with the World Bank Group, which was released in October 2018, found that the BRI will reduce shipping time for both BRI countries and non-BRI economies. On average, the BRI can reduce shipment time between any two countries in the world by 1.2 and 2.5 percent and reduce aggregate trade costs between 1.1 and 2.2 percent. For economies involved in the BRI, trading costs are estimated to drop by 1.5 and 2.8 percent.

Another study led by World Bank economist Nadia Rocha showed that BRI infrastructure improvements could increase total trade among BRI economies by 4.1 percent. When reduced time is combined with halved tariffs, trade among BRI economies increases by 12.9 percent. On average, exports from low- and lower-middle

income countries will increase by 38 percent.

Another study conducted by AidData – a US-based project that tracks development assistance – found that Chinese government-financed infrastructure projects have helped to narrow economic disparities within a country by bringing economic growth to secondary cities. Tracking the economic growth impact in 138 countries of 3,485 infrastructure projects including airports, seaports and roads between 2000 and 2014, funded by both Chinese and Western donors, AidData found that a 10 percent increase in Chinese development finance corresponded on average to a 0.6-1.1 percent increase in nighttime light output, roughly equivalent to a 0.2-0.3 percent increase in subnational or regional GDP. By comparison, the study found no evidence that projects funded by Western donors, which it said tend to be located in wealthier areas within host countries, narrowed income disparity.

According to Li Mingjiang, an area to improve for China in promoting the BRI is to better understand the domestic politics of the host countries. Li said that based on China’s own experience, Chinese decision-makers tend to examine the feasibility of a project with a time span of 20 years or more, but given a different political system, politicians in many host countries tend to examine a project with a time span of only a few years. “The result is that when there is a leadership reshuffle, the BRI projects and China can easily become a scapegoat for domestic political struggles,” Li said.

A Chinese-invested solar plant in Ghana, April 14, 2016

Source: Ministry of Commerce

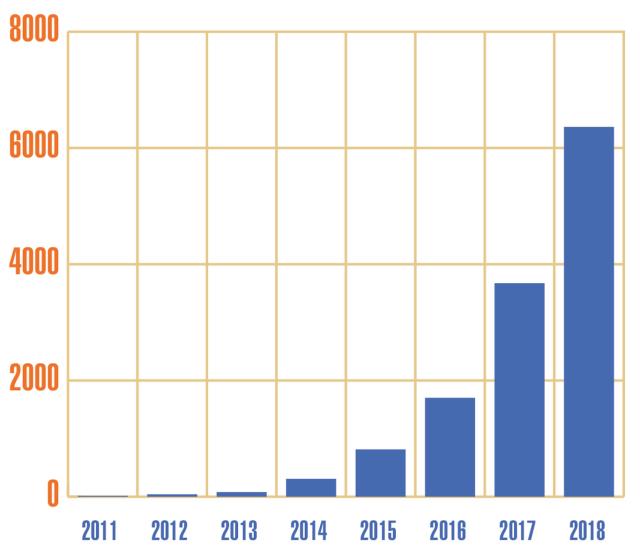

Source: yidaiyilu.gov.cn

Multilateral Platform

With various problems and mounting criticism emerging in the past months, China has notably changed its approach to the BRI. A major adjustment is to seek stronger cooperation with European countries.

In early April, China signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) on advancing the BRI with Italy, which became the first G7 country to join the initiative. In March and May, China also signed BRI agreements with Luxembourg and Switzerland. As Europe’s major financial centers, Luxembourg and Switzerland’s moves to join in the BRI are considered an important step in promoting cooperation between China and European countries on the issue.

Among the list of 283 deliverables achieved during the second Belt and Road Forum, several major deals were signed between China and EU members. These include an agreement between China and the EU on a joint feasibility study for a “comprehensive transport corridor.” Other agreements include a memorandum between China and Italy, Luxemburg and Cyprus, a memorandum with Austria and Sweden on developing third-party markets, as well as a bilateral agreement on a “digital Silk Road” with Hungary and a three-year cooperation plan with Greece. While many European governments share the same concerns as the US that the Belt and Road may become a geopolitical tool for Beijing, China is now increasingly promoting the BRI as a multilateral platform through which participating countries can cooperate with each other.

At a BRI seminar held in Beijing in August 2018, Chinese President Xi Jinping said that the BRI is not about creating a “China club.” “The BRI is an economic cooperation initiative, not a geopolitical or military alliance,” Xi said, “It is an open and inclusive process, and not about creating exclusive circles or a China club.” During his speech at the forum, Xi reiterated that the BRI is not an “exclusive club,” and China will promote transparency and green development of BRI projects.

“Being proposed by China, it is natural that China took the lead in advancing the BRI, but it has always sought to make clear that the initiative is open and inclusive,” reads an editorial published on March 31 by Chinese State-run English newspaper the China Daily.

Chinese officials also pledged to address various problems found in some of the projects. Liu Kun, China’s Finance Minister, told the media prior to the forum that China will establish an analysis framework on debt sustainability for Belt and Road projects to “prevent and resolve debt risks” and that Chinese financial institutions will be asked to enhance debt management. Yi Gang, governor of China’s central bank, also pledged that China will follow market principles and rely on commercial funding rather than State funds to finance Belt and Road projects.

BRI and the Trade War

Given China’s more moderate tone about the BRI and the intensified trade war with the US that may lead to challenges for China both at home and abroad, many Western analysts have suggested that China is now pulling away from the BRI, with some even declaring that the BRI is already “dead.”

But for most analysts, while China appears to have changed its tactics, the BRI remains at the core of its foreign policy. According to Gu, the BRI started as a defensive strategy when it was launched six years ago as a response to the “Pivot-to-Asia” strategy and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a free trade deal launched during the Obama administration.

“When the US vowed to deploy more than 60 percent of its military might in the Asia-Pacific, it posed a major threat to China’s major trade routes in the region,” Gu said. “China sought to extend its trade ties westward along the ancient Silk Road at the same time as economic and military pressure from the US,” Gu added.

While the Trump administration scrapped the TPP, its unilateralism in dealing with its trade disputes with China, which has dragged China into an escalating trade war, turned out to be more damaging.

As Beijing started to feel the impact of the trade war in the past months, China has started to bundle the BRI countries together as a single bloc in assessing China’s trade and investment landscape.

In a briefing released in February, MOFCOM announced that the trade volume between China and the 65 BRI countries increased by 16.3 percent in 2018, 3.7 percent more than the overall growth in China’s total trade growth. In total, trade with BRI countries reached US$1.3 trillion, accounting for 27.4 percent of China’s total trade volume, MOFCOM said.

A more recent briefing showed that the trade with the US dropped to 11.5 percent of China’s total foreign trade from 14 percent in the first four months of 2019 as a result of the

ongoing trade war. By contrast, the share of the trade with BRI countries increased to 28.7 percent, with a growth rate of 9.1 percent, a rate more than double the overall trade growth of China.

In a report titled “The Belt and Road Trade and Investment Index,” a study released on May 7 and conducted by financial data firm Refinitiv, the China Center for International Economic Exchanges, the University of International Business and Economics, and China Development Bank, the BRI grouping is described as the world’s second-largest trade bloc.

“In 2017, trade within BRI countries accounted for 13.4 percent of the world’s total trade volume, surpassing the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) to become the world’s second-largest trading bloc only after the European Union,” reads the report.

It appears that China now increasingly views BRI countries as a major bloc that will help China withstand the impact of its trade war with the US. This may also explain why the US has drastically intensified its criticism of the initiative.

According to Gu, given its growing importance in China’s trade landscape, China will not pull back from the BRI, as some Western analysts claimed, but it will take the BRI more seriously with its primary focus shifting to promote trade with BRI countries.

“It is only five years since China launched the BRI, which is rather a short period of time,” Gu said. “With a more prudent and wiser approach, the future prospects of the BRI remain desirable.”

Old Version

Old Version