As demand for pet dog cloning grows in China, the industry remains largely unregulated and faces criticism from animal rights activists

textNini died on October 7, 2018 at the ripe old age of 19. Around US$50,000 later, she was back in Zhang Yue’s life.

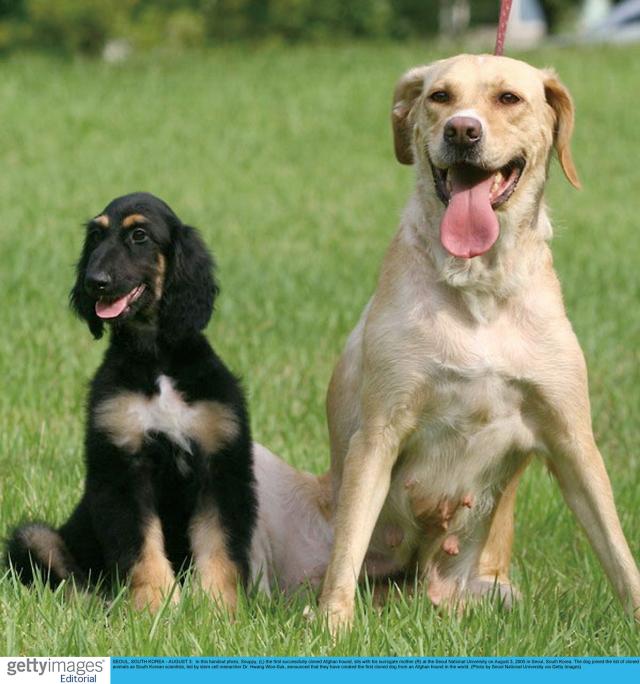

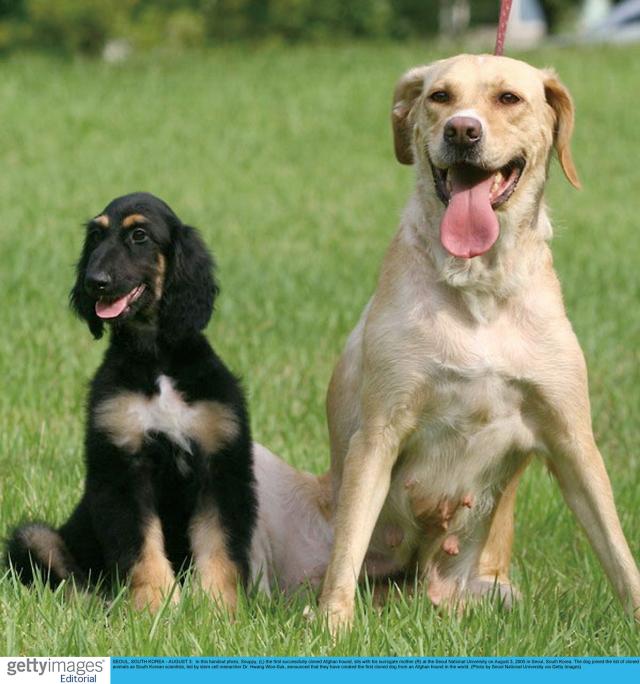

“When we first saw newborn Nini, everyone in my family said she didn’t look the same [as the old one]. They even cautioned me saying I might have been cheated,” Zhang, a wine dealer in Shanghai, told NewsChina in late December. “But I believed it was my Nini at first sight. They both had the same black hair on their backs and a similarly twisted tail.” It has been more than a decade since South Korean scientists cloned the world’s first dog – an Afghan hound named Snuppy. China followed with its first in 2014. Three years later, the country produced another canine clone, Longlong, using gene-editing technology.

Technical Challenges

While cloning research began in the late 1970s, it was in 1996 that Scottish scientists cloned the world’s first animal – Dolly the Sheep. Over the next two decades, scientists would successfully clone more than 20 different species, from mice to monkeys.

The method used is similar for most animals: It requires the injection of a somatic cell nucleus from the original donor into an extracted fertile ovum from a surrogate female. An embryo is created through in vitro activation, which is then transplanted to a surrogate mother.

But cloning a dog poses its own set of challenges. “The reproductive cycle of dogs is much longer compared to most other animals,” said Lai Liangxue, a researcher at the Guangzhou Institute of Biomedicine and Health under the Chinese Academy of Sciences and an advisor at Beijing Sinogene Biotechnology, a pet cloning and gene-editing firm. “Many animals are sexually receptive once every two to three days, but dogs require a more than 10-day cycle. So we must wait until the right time for the surrogate mother dog to become pregnant.”

“Also, the window to obtain a mature egg cell from the oviduct only lasts a few hours. If the egg is extracted at the wrong moment, it could deteriorate or burst,” Lai told NewsChina.

Lai explained that removing the nucleus from the egg is an extremely delicate procedure, and the high percentage of fat in canine egg cells makes transplants difficult. “The egg cells of cows, mice and humans are transparent, but those of dogs are darker. Plus, eggs may be damaged or die unexpectedly if not properly handled, or from sudden changes in temperature and environment,” Lai added.

After South Korean scientists produced the world’s first cloned dog in 2005, China and the US followed with their own successes. According to a 2017 article in China Science Daily, a Chinese firm cloned a Tibetan mastiff in 2014. Veterinary Practice News reported that in 2015, Texas-based company ViaGen expanded its business from cloning horses and other livestock to dogs and cats. In October that year, “Two litters of kittens were successfully delivered, followed a few months later by a Jack Russell terrier,” read the 2017 article.

“Cloning technology is mature enough and the market depends on demand and investment,” said Hu Xiaoxiang with the College of Biological Sciences at China Agriculture University. “As long as there is enough investment, cloned dogs are technologically feasible.”

Staff at Beijing Sinogene Biotechnology carry out surrogacy surgery on a dog, June 15, 2018

Booming Market

In early 2018, news that US singer-actress Barbra Streisand had her beloved dog cloned left a lasting impression on Zhang Yue. With her dog Nini fast approaching old age, Zhang began researching cloning companies online. She first found Sooam Biotech, a South Korean firm that charges US$100,000 per animal. But Zhang chose Beijing-based Sinogene after learning it offered the same service for half the price. In August 2018, Nini became seriously ill.

Considering the dog’s advanced age, her veterinarian advised against treatment. That’s when Zhang contacted Sinogene to have Nini’s somatic cells harvested and stored. Nini passed away that October. Sinogene began the cloning process soon after.

Zhang, single and in her early 30s, sees her dog as a family member. “I am adamant about trying new technology. As long as there’s a way to bring back my pet, I’m happy,” Zhang said. “I hope my clone can help rekindle the feelings I had [for my old dog].”

Mi Jidong, general manager of Sinogene, told NewsChina: “Chinese people have much deeper affection for their pet dogs than in the past, when most saw them as guards for the family house. It’s now common for people to see dogs as a part of the family.” According to the Chinese Pet Industry White Paper of 2018, China’s overall pet market reached 170.8 billion yuan (US$25.2b), an increase of 20.5 percent compared with 2017. Specifically, the pet dog market amounted to 105.6 billion yuan (US$15.6b), with cats making up 65.2 billion yuan (US$9.6b). Currently, there are an estimated 56.48 million dog and cat owners in China.

Mi said that rising incomes among Chinese pet owners have also helped breed confidence for the cloning industry’s future.

“Our industry research shows some hospitals providing clone or cell storage services for future cell-based therapies, but generally speaking, these pet services are limited, accounting for less than 10 percent of the total pet industry market. The high cost of the cloning process decides its high market price. We are trying to optimize that process to lower costs in the near future,” Mi said. At the Tianjin-based Boyalife research center, operations manager Li Lin told NewsChina: “While the main market targets high-income earners, there are also some owners who choose to clone the dog because they feel guilty for not taking good care of their dogs when they were alive. They’re looking for a chance at redemption.”

Zhang adopted the original Nini as a stray. “Nini is the only companion [for me],” Zhang said. “Despite the high price for a cloned dog, I think it’s worth the money because it can keep you company all the time. Compared with others who buy fancy watches or cars, I feel a dog is more valuable.” Sinogene charges 380,000 yuan (US$54,800) to clone a pet. At Sooam Biotech in South Korea, the price is US$100,000. To date, Sooam has cloned 1,200 dogs for clients across the globe. In 2014, Boyalife Group, a Chinese global biopharmaceutical holding company, and Sooam set up Boya Sooam, marking the official start of commercial dog cloning in China. US firm ViaGen began dog cloning nearly a decade earlier, but due to high costs and pressure from animal rights activists, the company suspended the service until 2016, an industry insider said. Now ViaGen can clone a dog for US$50,000 and a cat for US$25,000. Lauren Aston, the company’s marketing coordinator, told American Veterinarian in 2017 that “ViaGen has produced thousands of cloned horses and livestock over the past 15 years and is now approaching over 100 cloned puppies and kittens.”

Mi Jidong from Sinogene said that he expected to clone 300 dogs within the next two years. Since the second half of 2018, Sinogene secured more than 30 orders from clients. The company secured funding from Beijing’s Changping District government for technological innovations and started its third round of financing. It will soon provide cloning services for horses and cats.

The industry also has its sights set on cloning working canines. Because hereditary traits can be as equally important as training for guide, search and rescue, and sniffer dogs, cloning would help lower the costs of selecting and raising qualified canines.

“We are negotiating with the Police Dog Training Base under the Ministry of Public Security, and plan to use gene-editing technology to clone dogs better suited to their working environments,” Mi said.

“Dogs working in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region or Tibet Autonomous Region must be more adaptive to high altitude and low oxygen environments, while dogs in southern, more humid regions must have stronger resistance to heat and fatigue.”

Mi said the South Korean government has so far saved an estimated 35 billion Korean won (US$31.1m) thanks to gene-editing applications on working dogs.

Snuppy, the world’s first cloned dog, in Seoul, South Korea, August 2005

Lack of Supervision

South Korea leads the world in cloned dogs, something Mi credited in part to earlier dedicated research and easy access to canine egg reserves cultivated for the country’s dog meat industry.

However, Mi said the most important factor is that compared to Western nations, South Korea lacks legal restrictions and regulatory supervisions for animal cloning. Apart from human cloning, the industry is not legally prohibited.

“There is no country that has a specific law against dog cloning,” said Lai Liangxue. “As far as I know, the US and South Korea have not adopted any supervision policies or measures for commercial dog cloning.”

The same goes for China, Mi said: “We obtained the required certification to conduct animal experiments and are supervised by the local laboratory animal management committee.” The regional committee, Mi said, is only responsible for regulating the use of animals in scientific research, not commercial use.

In a lab back at Sinogene, Lai admitted there are factors in the process still beyond scientists’ control. Specifically, the natural genetic coding that takes place when a nucleus is transplanted into an egg. Even if the original dog is healthy, deformities may occur in their clones. An earlier report in 2014 described one of two male German shepherd clones as having a cleft palate and abnormal external genitalia.

If all goes smoothly, clones will physically match the original, differing only in the occasional birthmark or fur pattern. Furthermore, even though the clone may appear identical to the original, it may not have the same disposition or level of intelligence. This phenomenon also occurs in human monozygotic twins, who look identical but often vary in personalities and other traits.

Animal Rights Concerns

When cloning Snuppy in 2005, scientists in South Korea surgically transplanted more than 1,000 embryos to 123 surrogate females. Three became pregnant. One pup survived. Animal rights activists protested, saying the cloning firm puts the health and well-being of many animals at risk to fulfill the order of a single client.

Lai said the present technology does not allow for success from a single transplant. Instead, his firm tries to minimize the suffering of dogs during surgery with anesthesia and other measures.

“To successfully clone a dog, it is acceptable to make some sacrifices,” Lai said.

Despite regulations and terms authorized by the local laboratory animal management committee, there are no strict standards in place for surgery or technical operations on canines.

On its official website, the US Humane Society strongly objects to the cloning of animals for commercial purposes. “Cloning is a highly experimental procedure, with an enormous number of failures. Most cloned animals die in gestation or at birth,” continued the statement: “The relatively few survivors often suffer physical abnormalities, severe and chronic pain and other serious conditions.”

“A clone might look similar to my old dog, but it’s still not the original. Besides, it takes time to create affection and memories between owner and dog,” Li Xiaojing, a dog owner who lives in Beijing’s Haidian District, told the reporter. “It is ethically absurd, and I personally prefer to respect nature and life, rather than a cloned one,” she said.

Old Version

Old Version