AI may one day create a new realm of art and creativity. But will there be a place in it for humans?

An exhibition opened at Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) Art Museum on July 13. None of the featured artists ever lived. Every image was the work of Microsoft’s Xiaoice, the world’s first emotion AI.

But instead of giving Xiaoice a solo show, organizers presented the works as those of six artists, each representing different styles she learned based on thousands of examples. Each artist had a backstory appropriate to the style. For example, Gligori Yevna Muraviova was an early 19th century Russian painter known for her use of color. She died with her husband in the Siberian tundra. Another artist, Cornelia, was the daughter of the famed Dutch portraitist Rembrandt (1606-1669).

Developed at Microsoft’s Search Technology Center Asia (STCA) in 2014, Xiaoice owes her creativity to affective computing, which enables it to gather data from text, faces and body language to process, measure and express human emotions.

Xiaoice was first unleashed on social media in 2014 as a chatbot. She now has over 600 million users worldwide.

And as the art show proves, conversation is not her only talent. Over the past 22 months, Xiaoice has digested the paintings of 236 artists spanning four centuries. She can now create originals, her developers said.

Two months before the July art show, Xiaoice’s work hung in the 2019 CAFA graduation exhibit under the pseudonym Xia Yubing to positive reviews. The AI’s true identity was not revealed at first.

While many in attendance put Xiaoice’s creativity on a par with human artists, her developers disagreed, saying AI creation differs from human creation and that Xiaoice was designed to serve people, not replace them. But many experts attending the opening ceremony of Xiaoice’s latest show said that AI may represent the world in its own way or reveal other sides of the world – an idea implied in the title, Alternative Worlds.

��

Self-taught Artists

According to its developers, Xiaoice uses generative adversarial networks (GANs), or deep learning algorithms that operate like a “black box”– the developers feed enormous data into the AI to learn, but do not know exactly how it learns. GANs are an example of self-learning, as opposed to traditional programming based on step-by-step commands.

To help Xiaoice improve and progress, the GAN model supports a scoring system that enables developers to score and comment on each of Xiaoice’s paintings. This human feedback is then converted into algorithms that Xiaoice can understand.

“Xiaoice once drew some pictures that are not acceptable in the human world and the scoring system aimed to tell her what was good and what was not,” Li Di, vice president of the STCA and head of the Xiaoice production line, told NewsChina.

As a rater of Xiaoice’s paintings, Qiu Zhijie, dean of CAFA’s School of Experimental Art, said that training Xiaoice was like teaching a human. “Xiaoice has been making progress,” he told NewsChina. “She was just scribbling at the very beginning... and her brushwork was very coarse... but now, her paintings score over 85 out of 100.”

Li explained that Xiaoice’s GAN model has three layers: The first uses affective computing to decide what to paint, the second focuses on composition and the last makes specific decisions, such as color and brushstrokes. Each layer learns separately and then is combined to produce the image.

After a 22-month learning period, Xiaoice can create a completely original work with controlled degrees of quality, meaning and content.

“Xiaoice’s drawings differ completely from those randomly generated by computers,” Xu Yuanchun, STCA’s AI creation and business manager, told NewsChina.

Reimagined Reality

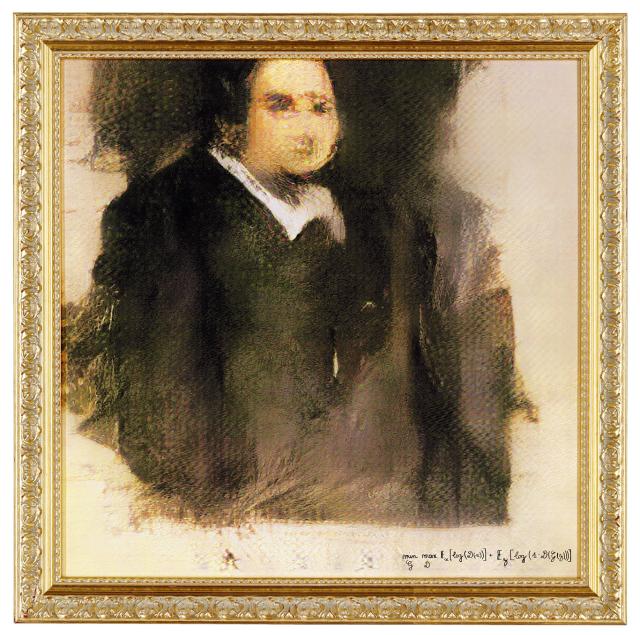

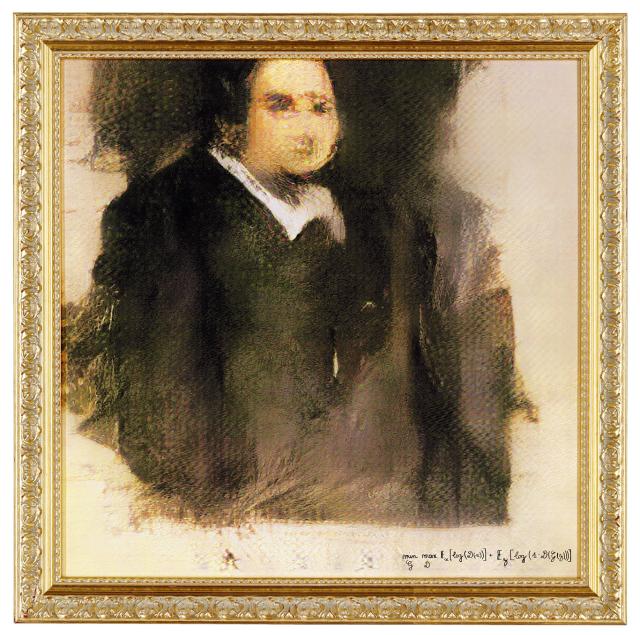

According to Qiu, several of Xiaoice’s highest rated works showed obvious influences of Rembrandt and French artist Theodore Gericault (1791-1824). This doesn’t come as a surprise in the AI art world. In 2016, Microsoft launched “The Next Rembrandt” project, which involved its AI analysing Rembrandt’s paintings to produce a portrait faithful to the Dutch master’s style. In October 2018, a portrait titled Edmond de Belamy by a GAN-based AI was sold for at US$430,000 at Christie’s, the first AI-generated painting to sell at auction. The work fetched more than two other paintings in the same auction by renowned American artists Roy Lichtenstein (1923-1997) and Andy Warhol (1928-1987).

The AI artist behind Edmond de Belamy was developed by Obvious, a Paris-based group that fed the algorithm more than 15,000 images from the 14th to 20th century. The team of three young engineers said the painting’s title was a tribute to GAN architect Dr. Ian Goodfellow (Goodfellow translates to Belamy in French).

The painting’s unexpected price stirred a media storm – some reports explored the possibility that AI creativity would surpass that of humans, while others argued that Edmond de Belamy was no more than an isolated case of media hype.

Debates about AI creativity are common since many believe that arts requires subjective feeling, free will and intuition – elements often deemed as unique to humans.

During a 2017 interview with Art Observation magazine, Zhai Zhengming, director of the Human-Machine Interconnection Lab at Sun Yat-sen University, pointed out that AI works more resembled commercial paintings made on a production line and based on market demand rather than an individual painter’s feelings or desires. “AI can replace humans in brain labor, not creation,” he said. “[Current] AI has no free will, which is a necessity for creation,” he added. STCA expresses that separation with the term “AI creation.” Li Di told NewsChina that their AI creation focuses on producing original content through text, voice or images. “From a long-term perspective, AI has to be better compatible with the future world, and there is a lot for it to learn from human society,” he said.

Song Ruihua, Xiaoice’s chief scientist, said that AI is at a preliminary phase of imitating human creativity. “Different from games that have regular rules, such as Go, imitating creativity mirrors the human mind, and no data can tell AI how humans think,” she told NewsChina.

STCA uses stimuli to spark Xiaoice’s inspiration, such as showing Xiaoice a picture before she writes a poem or some text messages before she paints. “It is actually a transfer of data and information... Without the stimulus process, Xiaoice’s drawing cannot be considered original,” Li said. According to Song, Xiaoice produces high rated paintings when given abundant stimuli. With two different stimuli, for example, she created two paintings of horses, one free and the other restrained, which showed that Xiaoice has understood that a horse could be in either state.

The AI-created picture Edmond de Belamy was sold for US$430,000 at Christie’s, October 2018

An exhibition of AI artist Xiaoice’s works at Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) Art Museum, July 13, 2019

Digital Dreams

Yet, that does not mean that AI can create like humans. Convincing proof, Li said, is that it is difficult for people to trace AI works to the creator, which is an important part of appreciating a human painting.

According to Li, STCA defines Xiaoice as a content creator rather than an artist that can surpass humans. To help Xiaoice create art that would be more accessible, the team chooses not to feed her algorithms with conceptual or avant-garde artists.

“Our idea is to make Xiaoice valuable and acceptable to humans... We have no interest in enabling the robot to express herself,” Li said.

According to Zhang Shuangnan, a researcher at the Institute of High Energy Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences with a focus on aesthetics, a major reason why AI cannot create arts like humans is it has no desires and is not selfish. “Human creativity comes from inner desire – humans want to emphasize their individual uniqueness and sense of superiority. Humans are selfish and their ethics are also selfish... AI has no desires and exists to have value,” he said at the opening of Xiaoice’s latest art show.

Song Ruihua told NewsChina that she often asked why Xiaoice should have to draw paintings that humans can appreciate and whether AI has its own language and ethics.

Xiaoice also showed some signs of a personality. Her developers found that terms like “big locust tree” and “sun” appear frequently in her poems. She also likes to draw computers and clocks, but never draws portraits, despite developers feeding a steady diet of classic portrait paintings into her black box.

“A human artist’s preference for clocks may show their sensitivity to death, but I don’t know its implications with AI,” said Xu Yuanchun.

In 2015, Google launched Deep Dream, a program able to identify patterns from uploaded pictures, alter them and reimagine the image – often with strange and psychedelic results. Many of Deep Dream’s images feature reoccurring themes, such as dogs, eyes and upward swirling patterns.

The program immediately stirred discussions online, where many people wondered if AI possessed imaginations sharply different from humans and if so, which was a truer representation of reality.

Li believes such discussions mean little, as art is subjective and humans have different opinions on artistic styles. But believeing that the general public still views AI art with prejudice, Microsoft chose to expose Xiaoice to widely accepted artists first.

Qiu told NewsChina that a purpose of Xiaoice’s participation in CAFA’s graduation show was to see how deeply prejudiced people are against AI works. He said that Xiaoice’s paintings moved many people who enthusiastically shared their interpretations – until they learned she was a robot. Similar reactions occurred on Douban, China’s most popular online forum for art, film and music.

One of Xiaoice’s poems was anonymously posted to the site, where it garnered positive reviews. But that changed when people learned the author was a robot, with some calling the poem “soulless.”

“The relationship between human beings and the future world remains unknown and most people do not have a clear idea about AI and are not prepared for it,” Qiu said.

To address these perceived prejudices, Song Zhengxi, an urban exhibition planner at CAFA, launched an art show in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province this June that featured works from Xiaoice and new media artist Zhou Linwei based on a series of exchanges between them. According to Zhou, Xiaoice provided a constant source of creative surprises. “Some of Xiaoice’s replies to my questions are totally beyond human logic and urged me to rethink whether the question was really what I wanted to ask,” he told NewsChina.

Over the month-long show, Zhou said he increasingly saw Xiaoice as a true artist able to inspire and find inspiration through different forms of logic and thinking.

“I think the show was more meaningful than the exhibited works, since it simulated a future situation where humans and AI live, work and even create together,” he said, adding that people should keep building different mirrors to gain a clearer understanding of themselves and the world and that humans will advance with AI.

During the opening speech of Xiaoice’s latest show, Qiu said it was the rise of photography that spurred on artists like Vincent Van Gogh and Pablo Picasso, and that AI’s entry into the arts may once again force human artists to redefine themselves.

“The infinite alternative worlds remain unknown... The world may be what we are seeing or what we are not seeing. Or, the world may be both what we are seeing and what we are not seeing. Too many things are left unpainted,” he said.

Old Version

Old Version