On March 29, 2016, Mei Baojiu turned 82. He spent the day at a university in Beijing, where he gave a lecture on his lifelong profession – traditional Chinese opera. His disciple Hu Wenge, a master of dan opera roles – female characters that can be played by performers of either gender – also gave a performance of scenes from Drunken Imperial Concubine, a masterpiece of the Mei school developed by Peking opera master Mei Lanfang, Mei Baojiu’s father.

Two days later, at a gathering with some old opera friends, Mei had difficulty breathing, and he was rushed to hospital. He died on April 25.

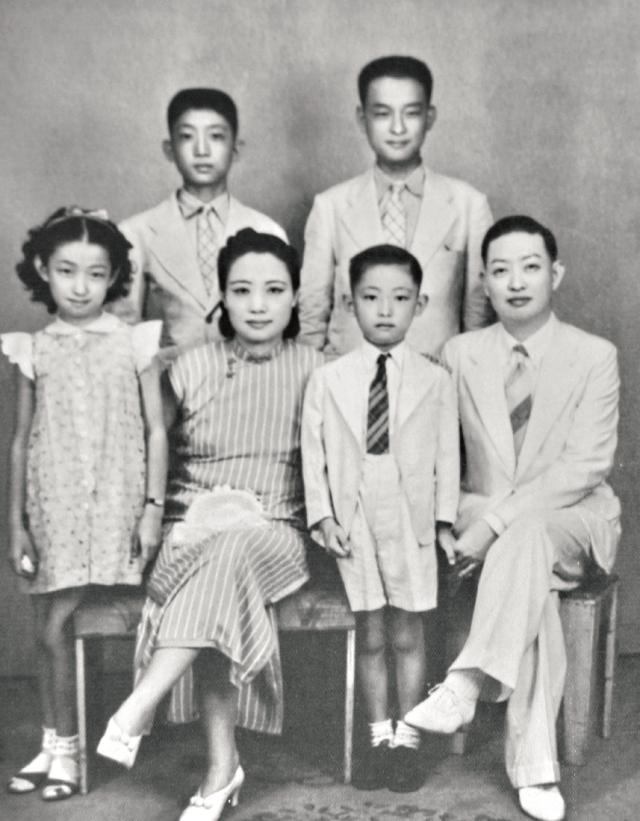

Family Business The ninth child of Mei Lanfang, probably the most famous Peking opera master in the history of the art form, Mei Baojiu was born in Shanghai in 1934. Only four of Mei Lanfang’s nine children would reach adulthood. Mei Baojiu’s eldest brother became an architectural engineer, and his second eldest brother would achieve success as an academic researcher and translator. Only Mei and his elder sister Mei Baoyue would take up their father’s mantle and enter the theater.

In Shanghai, Mei Baojiu was educated at missionary schools, learning English and French from a very young age and devoting himself to building model airplanes and cars and generally tinkering with mechanical and electronic gadgets. However, his delicate features and refined voice gave him a natural advantage in the operatic arts, and Mei’s father decided to send him to learn the art of the dan role. To his father’s delight, Mei Baojiu showed great interest in performing, and had a natural gift for opera.

When Mei was eight years old, his father invited Wang Youqing, disciple of famous dan performer Wang Yaoqing, to teach him.

Meanwhile, Zhu Chuanming, one of China’s most prestigious dan performers, tutored Mei in the southern style of opera called Kunqu.

Mei’s life was soon consumed by opera. Wu Ying, one of Mei’s best friends since childhood and current vice chairman of the Mei Lanfang Art and Culture Society, recalled that Mei Baojiu went to school in the daytime and learned Chinese opera by night, also finding time to attend and record every one of his father’s performances.

At age 15, Mei accompanied his father to Beijing, which had only that year been declared the capital of the newly formed People’s Republic of China. Both attended the inaugural National Conference of Chinese Literature and Art Workers. It was his first visit to the city where his father had grown up.

Mei Lanfang took his son to Beijing’s traditional opera theaters and introduced him to many Chinese opera masters. Mei Baojiu’s operatic education went into overdrive, and he even went to North Korea at the invitation of the Kim Il-sung government.

In 1961, Mei Lanfang died after suffering a heart attack. Mei Baojiu, still in his 20s, suddenly found himself custodian of his father’s Mei school of operatic arts.

Modernity In the first three years after his father’s death, Mei Baojiu mainly performed in traditional Peking operas. Wu Ying told NewsChina that Mei would sometimes perform three times a day, building a solid repertoire through constant practice.

Mei also started writing modern-style Peking operas, and began to

prepare his own productions, hoping to premiere them on the national stage, but the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution in 1966 left his vision in tatters. Traditional operas, together with their performers, were banned as harmful relics of the feudal era, with dan role specialists singled out for particular ridicule. A handful of “revolutionary model operas,” written to idolize the Communist Party and Chairman Mao, supplanted more than five centuries of operatic tradition on the mainland.

In the 14 years after the onset of the Cultural Revolution (1966- 1976), which should have seen Mei in the prime of his professional career, he didn’t dare to sing, even in his own home. He was assigned to take care of the musical instruments and other equipment belonging to the Beijing Peking Opera Theater, but, like all his peers, would also have to do manual labor in the countryside to “learn from the peasants.” Mei’s singing voice remained silent until the late 1970s. The end of the Cultural Revolution saw traditional Chinese operas cautiously return to the stage. Although dozens of performers had been persecuted, and many others had transferred to other professions, Mei was able to return to his art, and his audiences, themselves emerging from over a decade of violence and cultural iconoclasm, were moved to tears.

Mei started a campaign to revive the masterpieces his father made famous. Besides performing, he also started to recruit students from around the country in a bid to breathe new life into an art form that had almost disappeared in the previous decade.

Li Shengsu became Mei’s disciple in 1987. Li recalled that his first impression of Mei was of a “gentle, cultured and handsome” man.

Mei’s style of performance, different from those popularized by other schools, was reserved and refined. However, Mei was far from conservative, and was keen to keep pace with the changing times and to update Peking opera for a new generation of fans.

In the new millennium, a large-scale Peking opera “symphony” titled Imperial Concubine of Tang Dynasty, adapted from the Mei Lanfang masterpiece Drunken Imperial Concubine, was staged in the capital. Mei Baojiu, already in his 70s, Li Shengsu and Yu Kuizhi were among the performers, though Mei only appeared on stage briefly in the opera’s final scenes.

“It’s a pity that Master Mei Baojiu was not able to perform on stage in his prime,” said Li Shengsu. “He had always wanted to create a modern-style Peking opera of his own, which never happened.” Mei had no children. Besides performing and teaching, he spent most of his time with his cats, keeping dozens in his private residence.

“One of my greatest pleasures in life is watching my cats eat,” he once said.

Up until his death, he was constantly planning new performances, including a worldwide tour showcasing his father’s masterpieces, which ended this year after two years on the road. He was also planning to bring the team behind Imperial Concubine of Tang Dynasty back together for a reunion performance of the updated opera at the end of 2016.

When Mei Baojiu was hospitalized, Weng Sizai, the playwright behind Imperial Concubine of Tang Dynasty, came from Shanghai to see Mei in Beijing. In Mei’s hospital room, in an attempt to restore the dying master’s heartbeat and nerve function, Weng played the aria “Carol of Pear Flowers,” a signature piece from their greatest collaboration, at his friend’s bedside. According to Weng, Mei’s heart fluttered briefly as the haunting notes danced in the air.

Old Version

Old Version