China started paying more attention to the IC industry in 2000 when SMIC was established, and has continued to ramp up support for the field. In 2014, China Development Bank Capital, China Mobile, China Tobacco and several other State-owned companies launched the Big Fund, mainly investing in leading chipmakers and chip designers.

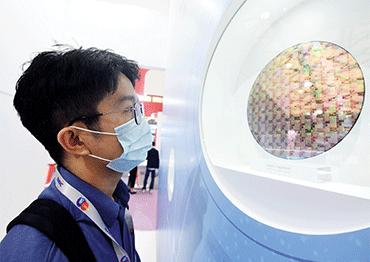

Driven by market demand and favorable policies, the IC industry expanded rapidly. In 2016, investment in China’s chip designing and manufacturing both surpassed 100 billion yuan (US$14.95b) for the first time. Local governments flocked to establish investment funds to attract projects. As of October, there were more than 50,000 registered chip related companies. In 2020 alone, more than 12,000 chip companies were registered, according to company data platform Qichacha.

Behind the rapidly expanding industry are bubbles at risk of popping. In July, Dongxihu District government of Wuhan, Hubei Province, posted on its website that Hongxin Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (HSMC) could halt its project for lack of capital. The company, established in 2017, attracted investment totaling 128 billion yuan (US19.13b). Its project was listed as one of Hubei’s major projects in 2018 and 2019 and had been top of the list of Wuhan’s major projects in 2020. The province has since removed HSMC from its list.

In recent years, it has become increasingly common to see semiconductor projects fail or teeter on the brink of failure because of broken capital chains. According to a September investigative report by Outlook, a weekly magazine under the Xinhua News Agency, at least six projects across five provinces boasting billions of yuan in investment were halted or declared bankruptcy.

In May, a wafer fabrication project that started in 2017 with investment from Global Foundries, a leading US wafer fabrication company, and the government of Chengdu, capital of Sichuan Province in Southwest China, suspended business. The planned investment for the project was nearly US$10 billion. This July, Tacoma Nanjing Semiconductor Technology (TNST) went bankrupt after launching a reported US$3 billion government-backed chip project in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province in 2015.

What all these failed projects have in common are local governments as their chief financiers while project initiators invest little to none of their own funds. Li Ruiwei, who launched TNST, was involved in three semiconductor projects with local governments in Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces between 2015 and 2019. Local governments took on all the financial risk. Shen Yinlong, vice director of Nanjing’s economic and technological development zone who helped introduce TNST’s project in Nanjing, said the project, the first one in the zone, was started in response to the country’s call to develop the semiconductor industry. The company sought an investment of 2-3 billion yuan (US$299m-448.5m). The local government declined. Then a similar project involving Li, who has been described in Chinese media as a “speculator,” was launched in Huaiyin District of Huai’an, Jiangsu in 2017. The district government spent almost all of its general public budget that year, more than 2 billion yuan (US$299m), to start the project.

Gu Wenjun, a semiconductor industry expert, told NewsChina that a current concern is that local governments are both investing and engaging in IC without enough knowledge about the industry. Instead, he called for local governments to set the stage and improve the business environment to attract investors.

“Many semiconductor projects are opportunistic. Local governments are so eager to get a project first that some projects are started without acknowledging their situation. Without investment or deep ties to the local area, the projects can retreat whenever they want. Some projects were established simply to cheat money,” noted Shi Qiang, an IC expert from the CCID Research Institute under the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology.

According to the interviewed analysts, most places can neither meet the capital, technology and talent-intensive requirements of the semiconductor industry nor invest as much as promised. Only a few projects are sustainable in the long term.

Also, the industry is struggling with redundant investment in low-level technology. TNST, for example, first promised to build an industrial park for contact image sensors (CIS, chips that can be used in smartphone or security surveillance cameras) in an agreement with Nanjing in 2015. After the project resumed in 2017, both parties realized CIS chips were too challenging and settled for second-best, less-demanding analog chips. Later that year, another of Li’s projects engaged in CIS chip manufacturing launched in Huai’an.

Cao Yun, who then worked in STMicroelectronics, a global leading semiconductor company, said TNST’s obsession with CIS chips confused him. “There were already leading Chinese companies developing CIS. Some foundries already owned mature projects and technology. TNST was not competitive enough to enter this arena nor it was necessary in terms of the national development strategy,” Cao said.

Investment is also chasing semiconductor power devices used for electricity control and conversion. According to Shi Qiang, many companies just produce, or plan to produce, lower-end power devices, after they fail to produce more advanced models. “There are too many products at the same technological level on the market,” Shi said.

There is also hype surrounding projects boasting third-generation semiconductors. Chips made with silicon are considered first-generation. Third-generation semiconductors are made from a compound of carborundum and gallium nitride. The anonymous analyst told NewsChina that third-generation semiconductors are not comparable with other semiconductors and not a replacement. “They have different uses, but their market share is less than 1 percent. Many projects use new concepts [like this] to reel in local governments.”

Wei pointed out that the planned capacity concentrates on chips of 40-90 nm may cause excess capacity in the domestic semiconductor industry. Combined with a lack of capacity for making advanced chips, redundant development will dilute investment directly.

Cao Huanshi, founder of Shanghai-based Qiezi Management Consulting which specializes in IC, observed that few among the 3,000 chip design companies possess their own intellectual property or can produce high-end chips. However, many seek a public listing as soon as they design a new chip.

“There is a recklessness among local governments and investors chasing the emerging industry, which causes bubbles,” Shen said.

Old Version

Old Version