In 2002, Shanghai Mental Health Center admitted only one patient for eating disorders, with another eight seen as outpatients. Those numbers began to increase in 2005 and have surged since 2012. In 2016, the hospital saw 1,100 people for eating disorders, and 2,700 in 2019.

Li told NewsChina that during the 1990s, Peking University Sixth Hospital treated less than 10 patients for eating disorders annually. That changed in the 2000s. In one of her papers, Li wrote that her hospital treated 104 people with eating disorders between 2001 and 2005, three times the total from 1993 to 2004. In 2011, the hospital opened a department specializing in eating disorders.

“Several years ago, cases peaked generally during summer and winter school vacations and we’d have space once the semester started... but in the last two years it’s been constant. There are so many patients,” she told NewsChina.

Chen Jue at Shanghai Mental Health Center attributed the increase to China’s growing economic development, distorted values regarding appearance and biased societal beauty standards. Body image trends that went viral in 2015 and 2016 only perpetuated these distortions. In the #A4waist challenge, women photographed themselves holding a piece of A4 paper vertically to hide their waists, a width of only 21 centimeters. Another viral challenge involved women balancing stacks of coins on their protruding collarbones.

These body image biases are prevalent on Chinese campuses. The mother of a junior middle school student told China National Radio this April that her daughter had always been sporty, but she scored low on the physical education portion of the national high school entrance exam because she had a higher than average BMI (body mass index), which damaged her daughter’s self-esteem. According to the report, many local governments include student BMI among the criteria for school evaluations. As a result, schools are encouraged to factor the BMI into students’ physical education scores.

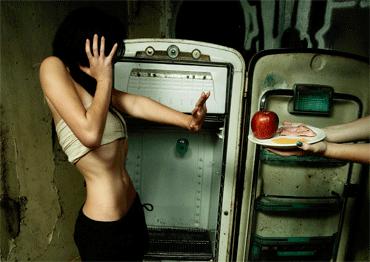

Under these pressures, more Chinese girls and women are developing eating disorders, a trend reinforced by the use of devices and non-prescription emetic drugs to induce vomiting that are readily available online. Meanwhile, those who are overweight increasingly face fat-shaming and are criticized for lacking self-discipline. In a 2019 survey of 265 female university students, psychologists Ren Fen and Wang Yanxue with the University of Jinan in Shandong Province found a positive correlation between anxiety over physical appearance and eating disorders.

The disorder is starting to affect younger age groups and people in rural areas. Li and Chen told NewsChina they have treated patients as young as seven years old. China National Radio cited a 2012 study in Shanghai which found that among the children and teenagers surveyed, 1.3 percent of primary students, 1.1 percent of middle school students and 2.3 percent of high school students suffer from eating disorders.

Prevailing standards of beauty are a big obstacle for treating disorders, according to Li. One of her patients refused further treatment when her weight increased to 42.5 kilograms. She told Li that she could not accept being heavier than 42.5 kilograms because that is the exact weight of a pop star she likes. Li warned that social pressures, combined with lack of awareness, makes those with eating disorders reluctant to seek medical help.

Many are working hard to reverse the trend. Recently, Zhang and others created a support group on Sina Weibo that saw over 1,000 members join in the first few months. Some members with backgrounds in nutrition, psychology and medicine volunteer to give regular consultations and encourage sufferers to seek early treatment.

Doctors like Li are also making efforts to combat eating disorders by providing online diagnoses and through public awareness campaigns, especially at schools, to spread the message that weight does not equate to health.

Zhang recently held a photo exhibition that tells the personal stories of people struggling with eating disorders.

Yang recently was accepted to a graduate program for psychology, and in the future hopes to help those with eating disorders emerge from the darkness of depression, helplessness and self-reproach.

After receiving the good news, Yang posted to her WeChat: “The tall and sturdy banyan tree grows from closely woven roots that run deep into dark crevices in the ground. [Like those trees], I hope you can emerge from the darkness of eating disorders and live a flourishing life.”

Old Version

Old Version