Tang’s journey into popular science began in 2013 after starting his doctoral program at CAS. He was sent to an island to research cloned monkeys for 18 months. There was no entertainment or data coverage. Tang passed the time writing popular science articles. He published two or three a month on Guokr, a popular website for science and technology education founded in 2010.

Before Guokr, the only outlets for popular science were television programs and publications. Guokr gathered scholars, science writers and enthusiasts in China and abroad in an online community where they could engage in lively discussions on any sciencerelated topic.

In 2011, one year after Guokr was founded, Zhihu.com was launched. Now Zhihu has become China’s most popular Q&A platform. Questions on Zhihu range from academics and politics to pop culture and everyday life, and attract many well-known experts as contributors.

By 2016, Tang had published more than 100 online popular science articles and joined the Shanghai Science Writers Association.

In the same year, he started online popular science courses for young students. His online teaching experience provided him with new thoughts about how to popularize science.

Tang recalled an open course that he spent lots of time and energy preparing for. After a two-hour lecture, he encouraged his students to ask questions. But he never expected to get stumped by the first one.

“A student asked me, ‘Mr. Tang, what’s a cell?’” Tang told NewsChina. “I was so shocked by this basic question... For more than a decade, I’ve been in an environment where there wouldn’t be anyone who didn’t know what a cell is. From that moment, I realized that popular science figures like us perhaps haven’t thought hard enough about what our readers and viewers really need.”

In January, the China Association for Science and Technology released a new survey on the scientific literacy of Chinese citizens. The survey shows that in 2020, only 10.56 percent were scientifically literate.

“If popular science promoters just neglect the remaining 90 percent, that means we’re giving way to rumors, superstition, conspiracy theories and anti-intellectual culture,” Tang said.

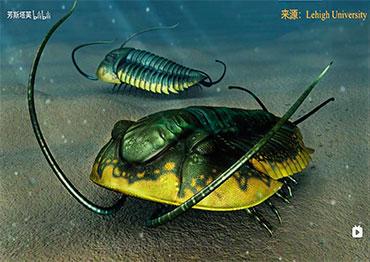

Encouraged by the immense popularity of his “strange shrimp” video, Tang adopted the format as his primary medium.

According to statistics from Bilibili, the content creators focused on science and knowledge sharing in 2019 rose by 151 percent year on year, while views of educational videos increased by 274 percent.

In June 2020, Bilibili launched a “knowledge section” with six categories: popular science, humanities and social sciences, technology, finance and economics, campus learning and workplace skills.

Old Version

Old Version