An announcement from China’s Ministry of Education instructing local universities and colleges in 12 provinces and municipalities to increase enrollment quotas for students from impoverished western regions has triggered a fierce backlash from locals, highlighting the stubborn regional inequalities in China’s education system

Many Chinese parents were holding their breath during this year’s gaokao, the national college entrance examination, after the Ministry of Education (MoE) announced in early May that local universities and colleges in 12 provinces and municipalities had to set aside a fixed number of places for candidates from 10 predetermined regions in the country’s impoverished hinterland.

According to the MoE, the policy is a response to central government directives to further develop the country’s impoverished west and close the regional educational gap.

Yet, given that universities and colleges situated outside major cities typically target potential students living nearby, parents in the localities named in the MoE announcement reacted with indignation, believing that the policy shift would undermine their children’s chances of a place at a respectable local university.

(In China, admission to college is based solely on a student’s gaokao score.) Soon after the announcement was made, parents in Hubei and Jiangsu, the provinces required to take the lion’s share of western applicants (40,000 and 38,000, respectively), gathered before their local education bureau offices, protesting the policy with banners saying “We Want Educational Fairness!” Another banner, an image of which later went viral on social media, simply lamented that what the MoE had “transferred” was not educational resources, but the hopes of local parents for their children’s futures.

The incident soon made front pages nationwide, with coverage gaining ground after the distribution of an open letter reportedly penned by a group of Jiangsu parents. “Our Jiangsu students do not dare to compete with the candidates from any other part of the country… What we want is fairness… It will do harm to the country’s competitiveness if the MoE plays a ‘quota’ game in higher education,” it read.

Under mounting pressure, and with public sympathy overwhelmingly favoring the protesters, the local education bureau of Jiangsu Province issued an official statement on May 13, claiming that the so-called “quota transfer” would not influence the recruitment of local students. “We promise that we will not reduce the total enrollment numbers earmarked for local students… We promise that the rate of local candidates admitted to firsttier universities will not be reduced, but instead, rise,” pledged the statement, referring to the most prestigious universities within China’s three-tier university system. The local education bureau of Hubei Province made a similar statement almost simultaneously.

Such pledges, however, did little to ease the anger and concerns of the protesting parents who argued that Jiangsu and Hubei provinces were far less worthy candidates for a quota system than Beijing and Shanghai.

The bulk of China’s best education resources are clustered in these two municipalities, and yet Shanghai only allocates a total of 5,000 spots to students from the west, while Beijing is not required to offer any.

The MoE’s quota adjustment plan has become a rallying point for more and more parents to join a snowballing national protest against regional inequality and unfairness in the college entrance examination.

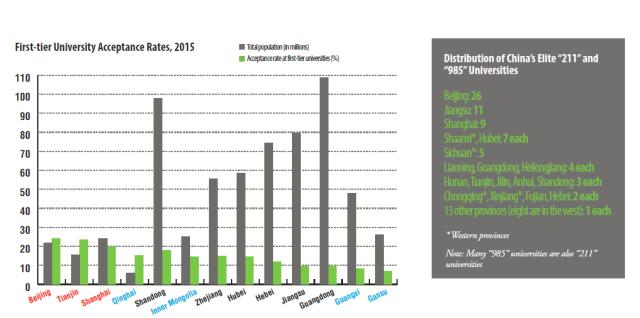

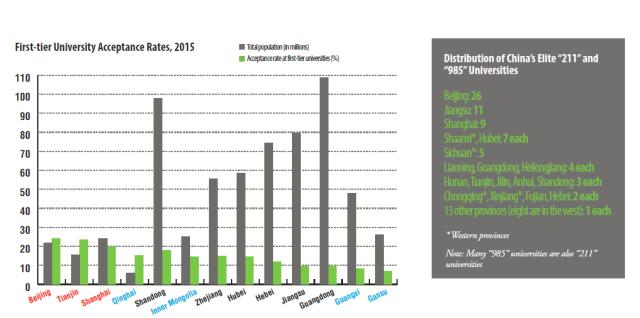

Red = municipalities Blue = western provinces

Conflict

To educators, the arguments made by protesting parents are not that understandable.

One college professor writing under the assumed name “Feiyang Nanshi” published an article on his WeChat account claiming that all schools, including those in Beijing, actually hope to accept as many students as possible to secure more profits and improve their reputations. However, he argued, the MoE has to control enrollment in order to preserve the value of college degrees. He also claimed that enrollment quotas are generally not allowed to move between provinces and municipalities once approved by the MoE, and that the recently announced quota transfers were the result of the affected provinces and municipalities attempting to “panhandle” more students by appealing to the MoE.

This anonymous blogger’s claims were later apparently confirmed by the MoE. During an interview with Xinhua News Agency, one education official, speaking anonymously, claimed that all the provinces and municipalities instructed to transfer their enrollment quotas had experienced year-on-year increases in college acceptance rates alongside a drop-off in the number of eligible candidates.

According to the same official, the college acceptance rate in Jiangsu Province increased to 88.8 percent in 2015, from 85.8 percent in 2013. Over the same period, Hubei Province saw its acceptance rate rise to 87 percent from 80.4 percent. Media reports also claimed that the number of gaokao candidates registered in Jiangsu Province had dropped for six consecutive years, while the number in Hubei Province had fallen for eight. This had caused some lower-ranked local high schools to fail to meet college enrollment targets.

Parents, however, come at the problem from a different angle, arguing that Jiangsu and Hubei provinces’ overall first-tier college acceptance rates, especially into “985” and “211” universities (particularly reputable institutions heavily subsidized by the government), actually fell far behind those recorded in other areas, including Beijing and Shanghai.

According to data collected by education portal gaokao.eol.cn, in 2015, 9.7 percent of gaokao candidates in Jiangsu and 14.4 percent in Hubei entered first-tier universities.

Among students from Beijing and Shanghai, meanwhile, the rates were 24.1 and 20 percent, respectively.

“What we truly care about is the [acceptance rate] at first-tier universities. Compared to Beijing, Jiangsu has fewer first-tier universities and fewer candidates admitted to those universities. So, why is it that we have to transfer our quotas?” asked one anonymous Jiangsu netizen in an online forum.

“Unlike many other Chinese provinces and municipalities, the education bureau of Jiangsu only allows about half of the province’s middle school students to enter high school, with the rest having to enter a vocational school [where the gaokao is typically not taken],” Ma Li, a Jiangsu native who participated in the gaokao several years ago, told NewsChina. “Meanwhile, those who fail their high school entrance examinations are also deemed unqualified to take the gaokao.” “I think this is the major reason behind Jiangsu’s dropping number of college candidates.

I don’t understand why us Jiangsu residents have to meet stricter requirements to get into college,” he added.

Many parents also attributed the reduced number of candidates to strict local observation of the now defunct One Child Policy.

Some argued that this sacrifice should come with material benefits, namely, an improved university acceptance rate to match the shrinking population of local candidates.

Gap

Reinstated in 1977 after all formal education was suspended during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), China’s gaokao is taken nationwide on set dates each year. Enrollment in the examinations, however, is done at the provincial or municipal level. Each year, universities work out the enrollment plans for each province or municipality and then submit them to the MoE for approval.

Candidates are only allowed to take the exam in the place where they hold permanent residency (hukou) and apply to colleges based on the enrollment plan in that jurisdiction.

This model, which the government believes tailors the system to the needs of different regions, has come under increasingly fierce fire for its unfairness, since most universities and colleges prefer to enroll local students. It is actually a problem of financing – most universities and colleges get the bulk of their financial support from their local governments. Although the “985” and “211” universities, including Peking and Tsinghua, receive much more money from the central government than less prestigious institutions, they remain dependent on local government support.

This has deepened resentment in Jiangsu and Hubei. “Peking University is for Beijingers and Zhejiang University is for Zhejiangers.

Why does Wuhan University [in Hubei’s capital] have to be nationalized?” ran one line in the open letter from disgruntled Hubei parents.

With the country’s highest concentration of top universities, Beijing has long been viewed as the epitome of unfairness in college enrollment. The capital, with a population of around 21.7 million, is home to 26 “985” and “211” universities, 15 more than Jiangsu, which has a population of 79.6 million.

“There is only one ‘985’ university in our province, so we have to try much harder in high school [than students in Beijing] to seize one of a pitifully small number of places that key universities offer to non-locals,” Wang Suna, a native of Hebei Province, told News- China.

According to Wang, when she took the gaokao in 1999, students from Hebei had to get a score of 546 out of 750 to be admitted to a first-tier university, while those from Beijing only needed a score of 460.

Beijingers, meanwhile, argue that they are losing their own advantages faster than students in other parts of the country. When the protesting parents in Hubei and Jiangsu provinces questioned why Beijing did not have to transfer any quotas to the west, an article by an anonymous Beijing parent claiming that “Peking University is no longer for Beijingers” went viral online. In the article, the writer claimed that Beijing universities actually have a much lower “localization” rate than those in other provinces and municipalities. For example, in 2015, Peking University reportedly enrolled around 4,000 undergraduates, 186 of whom were locals.

The same year, Zhejiang University reportedly accepted about 5,600 students, 2,100 of whom were locals.

This argument cut no ice with parents from other regions, however, who argued that Zhejiang University is the only “985” university in that province, and that Beijing’s smaller pool of candidates (compared to populous provinces like Zhejiang and Jiangsu) greatly reduces competition. Official data show that 61,222 Beijing students registered for the gaokao in 2016, one-fifth the number of those from Zhejiang, and one-sixth the number recorded in Jiangsu.

Causing further irritation for parents is the fact that, since 2002, China has required that regional versions of the test “better adapt to the educational conditions of different provinces and municipalities.” This has, many claim, further exacerbated unfairness – the tests given in Beijing and Shanghai, for example, are routinely slammed for being too easy, considering the outstanding educational resources available to locals. In the wake of the 2015 gaokao, a ranking of the relative difficulties of each region’s exam aroused considerable public ire, with Jiangsu’s version topping the list, while Beijing and Shanghai’s were ranked alongside those set in the impoverished west.

Although far from authoritative and with a methodology open to question, this ranking gave credibility to Jiangsu’s nationwide reputation for the extreme difficulty of its gaokao – so difficult that the public have dubbed the province “gaokao hell.” A 2010 report by edu.china.com.cn, another popular education portal, revealed that many gaokao candidates in Jiangsu Province wept while taking their test that year, later saying they could not understand some of the questions, never mind answer them. An anonymous teacher told Yangzhou Times, a local paper in Jiangsu Province, that the Jiangsu provincial mathematics test in 2003 was later regarded as a benchmark of what a difficult exam should be, adding that the 2010 test was “even harder.” Which is why the government’s pilot reform to lift hukou restrictions on gaokao candidates in Shandong Province failed.

With a 2015 first-tier college acceptance rate more than 6 percent lower than Beijing’s, Shandong’s colleges have limited appeal to non-locals. By comparison, a huge number of parents are struggling to secure a Beijing or Shanghai hukou for their children, reflecting the strict residency restrictions still imposed in both municipalities.

“We are taking the most difficult tests to meet a very high admissions standard. Is that fair?” asked Jiangsu resident Ma Li. “I worry that our province will one day become a place with a tiny number of highly educated people, looked down upon by outsiders.”

Large-scale protests over education issues are rare in China, so the recent demonstrations reveal the depth of public anger

Unsolvable

Far from leaving the gaokao alone, the national college entrance examination has been in an almost constant state of reform.

For the 2016 examination, 26 provinces and municipalities reverted to using a unified version set by the MoE.

However, given the unequal regional distribution of educational resources in China, the unified exams failed to satisfy critics of the system, who claimed they continued to disadvantage candidates from poorer areas.

In the past few years, experts have warned of the falling enrollment rate of rural students at top universities, which has declined by 10-20 percent since the year 2000, and continues to do so.

Some have therefore proposed removing regional quotas altogether, or boosting quotas for poorer regions, only to find themselves the target of anger from urban families claiming such changes would disadvantage their offspring.

“Honestly, I do not want Beijing to transfer any quotas, at least this year, since my son will take the gaokao this year,” Beijing resident Li Yong (pseudonym) told NewsChina.

“I may be selfish, but the gaokao is a core interest of all students and their parents. Nobody will agree to give up their share of the cake.” On many online discussion boards, the debate over gaokao quotas has escalated into mudslinging between regions, with easterners accusing westerners of stealing their quotas.

People in the west have hit back by attacking easterners for being happy to accept other resources, such as gas, from the west, while denying its sons and daughters access to their educational resources.

In an interview with ifeng.com, Peking University Professor Zhang Qianfan described the quota transfer as “robbing Peter to pay Paul,” and a move only likely to escalate conflict between regions. His words were echoed by many other experts who believe that a more sustainable way to support the west is to increase educational investment there through the construction of more and better universities, for example.

While the central government has taken multiple steps to support the west, including building more universities, few graduates are willing to remain there. Zhang Yiping, a Sichuan Province native who graduated from Lanzhou University, the only “985” university in western Gansu Province, told News- China that “all the non-local graduates from our department refused to stay in Lanzhou for work. Compared to our hometowns, Lanzhou is poorer in both its working conditions and development prospects.” She continued: “I do not think that Lanzhou natives would be willing to return to their hometowns if they were admitted to a key university in a big city, just as few rural graduates would choose to return to their villages after graduation. This isn’t a simple education or gaokao issue.”

Old Version

Old Version