n the Shenandoah River in the Blue Ridge Mountains of West Virginia stands a house that blends the architectural styles of China’s Bai, Tibetan, Naxi and Han ethnicities. Surrounding it are gardens of camellias and dahlias. Grapes will soon be planted for winemaking.

All of this is inspired by Southwest China’s Yunnan Province and built by summer camp students, mostly from Sidwell Friends School, a private prep school with campuses in Bethesda, Maryland and Washington, DC.

The project started with the Sidwell Friends School China Fieldwork Semester, a program designed and led by John Flower, a retired associate professor of East Asian Studies at the University of North Carolina Charlotte (UNCC), and his wife, Pam Leonard, a former adjunct professor of anthropology at UNCC.

From 2014 to 2018, students from Sidwell Friends spent four months each year exploring northwest Yunnan. Based at the Linden Center founded by American couple Brian and Jeanee Linden in Xizhou, Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture, students learned traditional craft skills like woodcarving, paper cutting and silversmithing, while also doing bike treks and studying Chinese language, history and culture.

In a 2016 trip to Cizhong Village along the Lancang River (upper reaches of the Mekong River), Flower and his students met Tibetan man Zhang Jianhua. Zhang invited them for tea and showed them around his two-story home. Flower was impressed, and when he learned that the land would be flooded due to a new hydropower project in 2018, he came up with the “crazy idea” to dismantle and move the house to the US.

He and his wife bought the house, and in September 2017, two truckloads of house parts were shipped from North China’s Tianjin to Baltimore, Maryland. Two years later, with support from Sidwell Friends parents, donors and student volunteers, as well as the West Virginia Timber Framers Guild and the local community, both the non-profit China Folk House and the house’s frame were established at the Friends Wilderness Center, a nature preserve along the Shenandoah River in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia.

Since then, China Folk House has become a place for “experiential learning, people-to-people exchanges, environmental stewardship and community engagement,” according to its website. Students at the site learn craftsmanship and gardening, as well as Chinese language, culture and cooking. They also explore the surrounding area through kayaking and hiking, and attend performances by Chinese and American artists.

Most of the rebuild is complete. Hempcrete, a carbon-negative material made of a mixture of hemp, lime and clay, has been used for the walls of the house. It is also fireproof. Tiles donated by the School of Architecture and City Planning at Kunming University of Science and Technology will soon be used to rebuild the roof.

In a recent interview with China News Service, Flower, who has left Sidwell to run the China Folk House project, explained why he believes a house can serve as a story of a family for better understanding of people, and how a rural house from China can help maintain people-to-people exchanges amid tensions between countries.

CNS: Can you update us on the China Folk House project since 2017, when the structure was transported to West Virginia?

John Flower: The update is that we have a lot more engagement with the Chinese-American community. Of course, we have school groups come in a lot. We’re kind of a museum and a place where schools come for field trips. That’s what I always expected. What I didn’t expect was two things. One is that we would have this summer camp that would be so popular with students wanting to build. One thing that’s really developed, I think, is a strong hands-on experiential learning program of building skills, culinary arts and traditional crafts that has developed since it’s been reported on [by media about three years ago]. It’s really developed into this place where there’s a center for experiential learning. And then the other thing that I never expected is how many Chinese American community groups have come out. Whether it’s the Yunnan Native Place Association, which is natural, or the Peking University and Wuhan University alumni associations, the Healthy Hikers’ Group, or the Chinese American parent associations of Montgomery County and Fairfax County. So, I think for a lot of Chinese Americans, they see this as a connection to their cultural roots. And they like their kids to come over. Many of their kids have never seen this kind of reflection of rural China and rural Yunnan. That is really, really special because it makes it so that we are doing people to people exchanges.

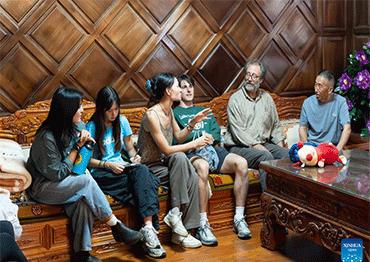

The third thing is we started taking students to Yunnan again after Covid. I took a group of 28 students last year. I have 20-some students this year. That’s great, because it means we are one end of a bridge, and the other end of the bridge is in Dali, Shangri-La, that northwest Yunnan region. We had groups of kids from Malipo [a county in Yunnan] come here this year. Usually what I do is that American school groups come, we do Nine Big Bowls [set meal of nine dishes from some rural places in Yunnan Province] or Mongolian barbeque, some kind of Chinese food, and do Chinese activities. But when the kids came from Yunnan, we gave them a West Virginia barbeque, and we did a traditional square dance, with fiddle and banjo and a caller to tell people how to dance. We held it on May 4 [when a Yunnan provincial delegation had arrived with the children from Malipo]. This is just what we wanted. We became a center where people are coming back and forth. People were connecting people. That’s our whole mission, connecting people.

CNS: Why do you think of a house as a “text?”

JF: The house as a physical structure has all this social meaning. It has a family, it’s not just a museum. People lived there. So, when you get the story of a house, you also get the story of a home, which is a structure with a family, its people.

CNS: Is it a coincidence that a house from mountainous Yunnan, where three big rivers – the Yangtze, Lancang and Nu – flow from the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau, is being rebuilt in a mountainous area where West Virginia, Virginia and Maryland meet along the Shenandoah River?

JF: I knew I wanted to go from the Lancang River and the Himalayas to the Shenandoah and the Blue Ridge [Mountains]. That was kind of a commonality. There is a river and mountains. It’s from the countryside, it has to go back to the countryside. It’s a pretty natural destiny. It [the house] stands in the north and faces the south. Originally in Yunnan, the Lancang River flows from north to south. Here, the Shenandoah River flows south to north. It’s completely opposite. But that makes it perfect, because it came to a new place. It has the same elements but reversed.

CNS: Why did you choose to introduce Americans to rural China instead of modern China?

JF: The house is not very old. It was built in 1989. But in 1989, Cizhong [Village] didn’t have electricity, they didn’t have a bridge across the Lancang River. They had an iron chain bridge. When we took the house down, it was 2017. Everyone had cellphones, everyone had internet, they were selling their honey on Alibaba or on Taobao. There was a high-speed road. You could get on the high-speed train there. That’s less than 30 years to go from essentially a pretty ancient way of life. They had some improvements, things like chemical fertilizer and that sort of thing. But mostly their way of life was similar to what their grandparents and their great grandparents knew. But just the lifespan of the house has witnessed the most incredible transformation, which is the transformation of rural China in particular.

China, as a whole, has grown so much in the last 30 years, but I think one of the ways of telling the story of the house is it reflects the transformation of modern China, to go from in less than 30 years, no electricity, to being fully integrated into a modern world system. It’s incredible. So that’s part of the story that we have to tell about the house.

CNS: What story do you think a folk house from Yunnan tells American people?

JF: It humanizes China for people to see something specific like this, to see something related to everyday life. You know where the misunderstandings come. They come from abstraction. We demonize what we make abstract. You project your fears, your anxieties onto something that’s abstract. But here this was a house for Chinese people. And I think that’s the real magic of people coming here. And why it’s so important is that it humanizes, not demonizes, the Chinese people, because this is a reflection of how a community of people lived.

CNS: How would you explain “humanize” to Chinese people?

JF: Renqing [the Chinese word for “human connection”]. This place is all about this. This place is built by a circle of gifts. I bought the house from Mr. Zhang, but he wasn’t selling it to me for money. He knew this plan. People have done things not for money, not as a transaction, but as a gift.

I tried to get the guys from Jianchuan [a county in Dali] to come over to help us build. They would have built a beautiful pavilion here. But they didn’t get visas because of the tensions. I didn’t have an idea [on how to build the pavilion]. I know something about building, but I couldn’t put this up by myself or with students. So, who’s gonna come? I didn’t know.

I was giving a talk at a local community center [in 2019], at a barn, a local community here in the countryside. I was showing the film about taking the house down that’s on our website. I thought maybe a dozen people would come – 150 people packed this place, standing, no seats. They watched the film, and then at the end, I thought they were gonna ask questions about the fascinating community. Most people wanted to know: “How are you gonna get it back up?” and I had to say: “I don’t know.”

As I was leaving that talk, two guys, local West Virginia guys, came up and said: “That was pretty cool. We’d like to come and see if you need a hand.” I said: “That’ll be great.” Then next day all these guys came out. It was the West Virginia Timber Framers Guild. They volunteered for two weeks as a gift to put up the frame. The whole time they were thanking me for bringing such a cool thing, because for them it was fascinating. It’s a completely different way of [building] from what they do. They loved it, they thought it was really interesting. There were all kinds of things like that. People came. My students came. They donated their labor. People donated their money. It’s a circle of gifts. I try to give back by holding events for the public. It’s a deep Chinese concept and it so fits this project.

CNS: Do you expect that your project’s people-to-people exchanges can improve China-US relations?

JF: Yes. Especially when things are intense, people-to-people is more important than ever. When relations are tense, especially in the media, there tends to be this demonization. And what we’re trying to do is say, governments are their own thing. People, it’s all about people. And we fear and hate what we don’t understand. It’s as simple as that. But when you go someplace and you meet people and you understand and you make that kind of connection, all that fear and hate can’t exist. It can’t exist when people-to-people exchange happens.

I took 25 students last year, maybe 20 this year [to Yunnan]. I’ll keep doing it. Maybe do another program. Maybe in the wintertime, I’ll take another 12 students or something.

And then I would like to welcome Chinese students to come here. This is a great place to meet American students interested in China. Lu Xun [a leading Chinese writer in the 1920s and 30s] was all about where is hope. Hope can’t be said to exist, nor can it be said not to exist. It’s like a road. You have to make a road. “When many men walk one way, a road is made” [a famous quote from Lu Xun’s 1921 novel Hometown]. That’s what hope is. You have to go and do it.

I take students to China. Of course, they will see Beijing and Shanghai. But they should also get a sense of roots and get a sense of the countryside and how the countryside is changing. You have to know your past to be able to move into the future.

A lot of students now from America are going to China for a week. They go to Hangzhou and other big cities, and they go to university-level wonderful programs. But it’s a little whistle-stop tour. I’m trying to add a deeper element. I’ve got students for four months, a whole semester. Now if I have a month, I can give them something they will never forget. Go someplace, stay there. That’s our niche. That’s what we can contribute.

Old Version

Old Version