Cai Jun’s initial impressions of Shanghai’s workers came from his father, a senior worker at Shanghai No.3 Petroleum Machinery Factory. As a child, his father often would take him to the factory to attend cultural activities. He remembers almost every worker had hobbies involving art or literature. Some played the flute, some liked dancing, and his father was enthusiastic about photography.

With the deepening of the reform and opening-up policy since 1978, Chinese society experienced tremendous changes as its economy became marketized.

In the late 1990s, a wave of industry layoffs swept the country. The factory where Cai’s father worked began losing money and most of its workers were laid off. His father was among the few who remained.

Cai’s father had a young apprentice. He and Cai were the same age. Though Cai never met the young man, he heard lots about him from his father and felt a closeness to him.

Many years later, memories of this apprentice resurfaced. “I started to realize that we were like brothers. It was as if he was the other me who didn’t become a writer but instead inherited the skills and the spirit of industry and perseverance from the workers of my father’s generation,” Cai told NewsChina.

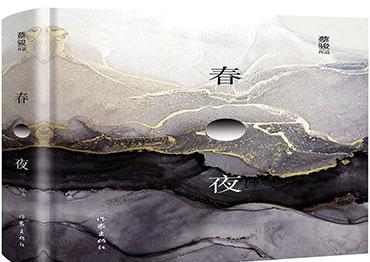

Based on the apprentice, Cai created Zhang Hai, the protagonist of One Spring Night. The novel revolves around two unsolved cases in the State-owned Chunshen Machinery Factory near the end of the 1990s: the murder of a senior engineer and a new factory manager who disappeared with money raised from the workers to save the factory from bankruptcy.

The story is told in the first-person through Cai Jun, a young fan of literature whose father was a senior worker at the machinery plant. In the story, Cai Jun meets his father’s apprentice Zhang Hai and the two become friends. Cai and Zhang work together to solve the murder of the engineer and search for the missing factory manager. The two, along with a group of laid-off workers, start a journey to find the truth that spans more than two decades.

“One Spring Night can’t be categorized as suspense fiction, but it contains many elements of the genre. I blended these elements into the story to make it more dramatic and I added many cliffhangers to draw readers in,” the writer told NewsChina.

Compared to his past works, most of which feature long passages of formal language and standard Chinese, One Spring Night adopts more colloquial language, slang and the Shanghai dialect.

“Since I’ve woven lots of my own experiences into this work, the use of vernacular language enhances the sense of authenticity and reality,” Cai said.

From Cai’s perspective, when writing about Shanghai, writers tend to depict it as a modern metropolis for the bourgeois. But the working class constitute a large part of Shanghai’s history.

“Ever since the 1990s, with the deepening of the market economy, the establishment of the Pudong New Area and the further openingup to the world, Shanghai came to wear a new face. But more often than not people began to forget about or ignore the city’s appearance before the 1990s,” Cai told NewsChina. He hopes this book can reawaken people’s memories about the city and its citizens in the planned economy era – a forgotten side of Shanghai.

At the book launch of One Spring Night in Shanghai on December 27, 2020, Liu Ning, a news anchor on Shanghai Television, said she could feel Cai’s ambition to write about the history of the city. “The novel has the power to rekindle our collective memories about a particular history of Shanghai. The facts and social issues he wrote about in the book are extremely authentic and close to us, and they allow us to reflect on the past and present of industrialization in Shanghai over a century,” Liu said.

Old Version

Old Version