Crosstalk is in a state of stagnation,” says Yan Hexiang, a veteran performer at Deyun Club, China’s most influential crosstalk collective.

Originating in the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), crosstalk, or xiangsheng in Chinese, is among China’s most popular folk performance genres. It typically features two comedians in traditional costume exchanging banter, puns and jokes about contemporary life mixed with references to Chinese culture and history.

Crosstalk’s popularity has oscillated over the decades. It fell out of favor during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), but resurged during the 1980s and early 1990s, reaching a nationwide audience through radio and television. However, a dearth of new routines and the rise of sketch comedy led to crosstalk’s decline by the late 1990s. In 1995, superstar crosstalker Guo Degang opened his Beijing-based Deyun Club and led a group of performers that in the mid-2000s brought crosstalk back to the mainstream.

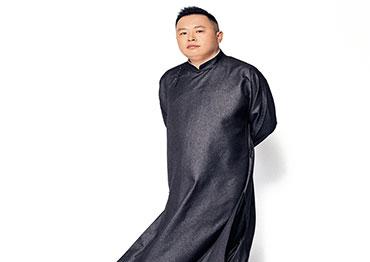

Yan Hexiang has been fascinated with crosstalk since childhood. Graduating from Beijing University of Technology with a degree in telecommunication engineering, Yan became a programmer with China Mobile in 2004. When Deyun Club held open auditions in 2006, Yan tried out and won a spot as a trainee. By 2009, he was apprenticing with Guo Degang. In 2016, Yan partnered with Guo Qilin, Guo Degang’s son and a popular crosstalk performer in his own right, for the third season of the variety show Top Funny Comedian. Yan quit his China Mobile job that year to perform crosstalk.

In an interview with NewsChina, the 39-year-old comedian addresses his concerns over the underlying problems of the crosstalk industry – lack of creativity, the side-effects of celebrity culture and competition from stand-up comedy, which over the last 10 years has seen a meteoric rise.

NewsChina: You first saw Guo Degang perform in 2005. What did you think?

Yan Hexiang: I remember he performed a monologue and the traditional crosstalk routine “Brains and Brawn.” He’s an extremely innovative performer who has adapted plenty of old crosstalk routines. He mixed in the latest internet slang and current social issues. Guo is a shrewd observer of society who blends his observations in his performances. He is way better at capturing the times than many current crosstalk comedians.

NC: What did you learn during your years with the Deyun Club?

YH: When you become an apprentice there, Deyun Club breaks down all your pride right away. It makes you feel like you’re worthless, humbling you enough to earn classic routines and go through the pains of practicing basic skills. One tricky thing about spoken word performance art is that once you learn a comedy bit and get laughs, you can get complacent and unwilling to do more. Modesty, industry and tenacity are important values for training with Deyun Club.

NC: Many Deyun Club performers have groupies who call themselves “Deyun girls” and idolize them like pop stars. What do you think of this recent change?

YH: This form of celebrity culture came from Japan and South Korea. After arriving in China, it fit with certain aspects of crosstalk. Since crosstalk involves a lot of crowd work, it satisfies the fans’ desire to know and interact with their idols.

NC: Will this adulation go to crosstalkers’ heads?

YH: Some people go to a crosstalk show mainly for the performers they adore, some for the show itself, and some for both. The thing is that right now, fans of certain performers have the strongest online presence. They passionately – if not blindly – express their love and appreciation for their favorite performers. As a result, performers might easily get carried away by their praise. We have to be clear that there are still many people who come out to see shows for the material and are not about leaving feedback online. We can learn more about how this group feels about our shows. If one day these people become disappointed with what we’re doing, they’ll just leave without a sound. This is really a big issue.

NC: Though shows at the Deyun Club are still popular, many feel that comedians there always perform old crosstalk routines. What do think about that?

YH: On the one hand, the creative process of today’s crosstalk is very different now. In the past, celebrated authors such as Lao She, He Chi and Liang Zuo wrote crosstalk routines for comedians. During the 1980s and the early 1990s, performers started writing their own material.

In the past, authors wrote short stories, sketches and crosstalk routines that portrayed real life in short and vivid formats. But nowadays we have many more channels, like short videos, films and variety shows. People write for these instead. Also, the crosstalk community doesn’t really collaborate with writers and intellectuals anymore.

On the other hand, there’s no denying we rely too much on old material. After the Deyun Club became famous in 2006, crosstalk performers revived lots of old routines. To be honest, it wasn’t because audiences really liked them, but rather because they had never heard them. So there was a time when we were reacquainting audiences with older work. Since there are plenty of old routines, there is a deep enough repertoire for the majority of crosstalkers today who are only interested in making a living. But because of this, people in the industry have lost the drive to write their own stuff.

NC: Younger crosstalkers seem complacent with performing old routines. Is this a crisis for the crosstalk industry?

YH: Of course it’s a crisis. That’s why we say crosstalk has stagnated. The lack of creativity reflects younger performers’ ignorance of this art. Many new crosstalkers don’t know anything about crosstalk when they start out. Lots of them don’t know the greats such as Zhao Peiru, Guo Qiru and Liu Baorui. They even don’t know (former household names) like Ma Sanli and Hou Baolin. They only know Yue Yunpeng (a younger crosstalk star). They don’t know how the art developed. They think crosstalk is all about telling old jokes.

NC: You once said the crosstalk industry is done for. Why?

YH: If crosstalk comedians keep performing old bits, audiences will catch on. When it becomes intolerable, a savior like Guo Degang will come along. The reason my teacher got so popular in the mid-1990s was precisely because people got tired of televised crosstalk shows. In the future, someone has to come and set everything straight. But before that happens, people in this industry will just be content with the status quo.

On the surface, the internet gives crosstalkers more opportunities to become known. But essentially the content we’re performing hasn’t kept pace with the times.

NC: In the 1950s, crosstalk masters such as Hou Baolin started a movement to clean up crosstalk and get rid of vulgar content. But lots of dirty jokes are told at Deyun Club shows. Is this a regression?

YH: Definitely. I really hate some of the prevailing anti-intellectual values in this industry. Many think that crosstalk performers don't need to be educated, and they can earn easy money and fame by telling vulgar jokes. It’s in poor taste. Many performers don’t know what real humor is all about.

NC: From your perspective, what are the differences between stand-up and crosstalk?

YH: Essentially there isn’t much difference. I think there should a broader definition of crosstalk, which can include stand-up, comedic monologues and more. But sure, crosstalk performers developed their own language skills and a more structured performance style over the years.

NC: Many believe that crosstalk is slower in rhythm and conveys less content compared with stand-up comedy. What do you think?

YH: The differences are there. A very important feature of stand-up comedy is that it usually deals with current affairs and hot topics. Performers tend to presume audiences are familiar with these issues. They don’t have to provide much background and can get straight to the point. Crosstalk comedians, however, presume audiences don’t know what they’re about to talk about, so they elaborate on the background before finally cracking jokes and delivering punchlines. But we must admit this form of narrative has failed to keep pace with the times. I think crosstalk performers must adjust our traditional ways of narration to keep up with the audience, because we’ve got to admit the times have changed.

A reason behind stand-up comedy’s popularity in China is that it’s more difficult for people today to delay gratification. They are less willing to wait for a slowly unfolding joke.

NC: You mentioned that stand-up comedians and crosstalk performers should learn from each other. Could you be more specific?

YH: The most important thing that crosstalk performers learn from stand-up comedians is their strong awareness of intellectual property (IP). In the past, the master-apprentice system was a way of protecting IP. But since the 1970s, crosstalk performances were broadcast on nationwide television. When a routine became a hit, lots of other comedians copied it. People often don’t know who originally wrote the material. This was still prevalent even after the Deyun Club got popular in 2006.

By contrast, stand-up comedy has strong awareness of IP protection and a strict code of ethics. Stand-up comedians never use someone else’s material. You’d be subject to harsh ridicule for stealing another comic’s joke. This code was in place from the very start, and pushes them to keep writing new material. This is exactly what crosstalk performers should learn from them.

NC: Do you think stand-up comedy will draw audiences away from crosstalk?

YH: Currently I don’t think so. Both have their shortcomings. The main problem for crosstalk is that performers haven’t fully recognized the significance of creativity and staying current, while stand-up comedians haven’t realized the importance of enhancing their language skills. These are indispensable elements for spoken word performing arts.

NC: If stand-up overcomes its shortcomings first, will it pose a threat to crosstalk?

YH: Absolutely yes. This is exactly where my concern lies. I always like to mention a comparison – perhaps it’s not accurate. The relationship between Chinese stand-up comedy and crosstalk is very much like that between dolphins and human beings. Dolphins are an intelligent species millions of years younger than primates, but they are evolving. Apparently, humans are smarter than dolphins right now, but you never know. One day dolphins may evolve to be more intelligent than humans.

For now and into the future, the market for stand-up comedy will remain in first- and second-tier cities. Therefore, there’s still plenty of space in third- and fourth-tier cities for crosstalk to develop. Crosstalk will still see an explosive rise both in popularity and in revenue. But it’s still possible that one day the market for stand-up comedy may expand to smaller cities.

NC: What are your plans for future performances?

YH: While on (TV show) Roast, stand-up comedian Yang Meng’en gave me a nickname: “The number-one solo performer of the Deyun Boy Group.” I really appreciated it. My dream is to become the number-one solo performer in Chinese spoken word. Perhaps for some time in the future, I’ll try different formats like dankou (monologue), pingshu (storytelling), stand-up comedy and speeches. I really hope to break down the walls between crosstalk and stand-up comedy, and those between dankou and pingshu.

Without these categories and labels, we’re all just standing on stage alone. We’ll perform a 30-minute set and let the audience judge our material… and they’ll decide whether they want to buy tickets for the next show. I hope we can bring the art of spoken word back to its roots and stop all this infighting and stagnation.

Old Version

Old Version