Behind the boom in shipping culture is a bleak reality. According to China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs, China’s single population reached 240 million in 2018, roughly the sum of the populations of Germany, France and the UK. More than 77 million adults in China live alone, as the data further shows, and the number is expected to rise to 92 million by the end of 2021.

Facing unaffordable housing prices, work pressure and increased costs of living, more young people in China are choosing to stay single and live alone. Some studies revealed that women have more reservations concerning dating and marriage than men.

In cooperation with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Chinese dating app Tantan surveyed the attitudes of Generation Z (those born after 1995) toward dating and marriage. According to the survey released in January, 70.7 percent of male respondents hoped to find a partner as soon as possible, compared to only 44.9 percent of women.

As more young women in China become educated and achieve economic independence, they are in some ways growing more resistant to traditional mores of marriage than men. Seeking a more fulfilling relationship is becoming the norm, a shift not only evident in major cities but also in smaller cities and towns.

Another survey by Tantan released on April 30, which interviewed over 3,000 millennials living in 68 towns and smaller cities across the country, reveals a stark difference between men and women in their attitudes toward dating and marriage.

Sixty percent of men said they would marry an “OK match,” but 65 percent of female respondents said they were unwilling to compromise their pursuit of a “high-quality relationship” with the right partner. Also, 41 percent of women said they were fine with “dying alone,” compared to only 20 percent of male respondents.

Shipping, to some extent, offers an alternative to young Chinese women looking to experience a “high-quality relationship.”

According to an online survey of 4,521 shippers by entertainment industry database FUNJI released on May 26, 99.2 percent identified as female and 86 percent were under 25 years old. Also, 90.3 percent said they were single, while 48 percent had never been in a relationship.

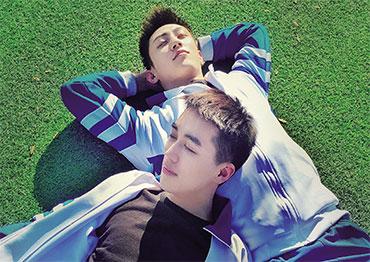

Shipping is a relatively safe way to enjoy the sweetness of love, according to Zou Qiyi, a 23-year-old graduate student at the Renmin University of China who is enamored with Gong Jun and Zhang Zhehan, the two leads in the 2021 web series Word of Honor, adapted from the boys’ love martial arts novel Tian Ya Ke by the web writer Priest.

“I’ve never had a relationship but I’ve been hurt countless times over meaningless flirting and unrequited love. Deep down I have fears and anxieties over love and relationships. But I’m comforted by the couple I’m shipping. I feel like I can experience what love is like through their relationship,” Zou told NewsChina.

Lin Xing, a young scholar researching pop culture at Fudan University, said shippers often refuse to face any reality that challenges these highly idealized intimate relationships.

“Usually shippers don’t really care about whether the relationship of the pairing they like truly exists. They avoid the reality of it, because deep down they all know it’s not as rosy as the mirage in their minds,” Lin told NewsChina.

Lin has learned that in many circumstances, shippers find emotional connections with one another in the world of fan fiction and art that they create.

“Shippers are very creative. They write fan fiction, draw art, edit videos and communicate with like-minded fans online. Some of these creators are really talented and produce quite high-quality work. They enjoy fandoms where they freely discuss, exchange thoughts, create and share their work. So in reality, fans are essentially loving each other, and loving the creative content they produce,” Lin said.

She points out like in other fast-paced East Asian societies, anxiety over the increasingly rare “hard currency” of intimate relationships is driving the shipping culture in China. “Intimate relationships are something that everyone lacks and everyone needs, but not everyone can get,” Lin said.

“I’ve shipped and I know perhaps they’re not real couples. But these sugary virtual romances give me some temporary comfort from my bleak, loveless reality. Essentially, it’s because deep in my heart I still believe in love so I’m hungry for these sweet stories,” said Qing Cheng, 24, who has shipped six couples.

“It’s very much like dangling a carrot in front of a donkey. Our life needs something sweet to get us through all the hardships. It doesn’t matter if that sweetness comes from natural honey, processed cane sugar or artificial sweeteners,” Qing told NewsChina.

Old Version

Old Version