The tragedy drew public concern about the development of extreme sports and marathons, which boomed in 2015 after the Chinese Athletic Association (CAA) did away with the approval system and lifted restrictions on race registration. Official data showed that in 2019, 1,828 marathons were hosted on the Chinese mainland, nearly four times the amount in 2014.

Although ultramarathons are less popular considering the greater challenge, their numbers also increased.

“100-kilometer ultramarathons started to become popular five to six years ago, and many regions, especially in southwestern and northwestern China with unique landscapes and terrain, organize ultramarathons as a way to promote local tourism,” Wei Bi a sports medic with experience working such competitions, told NewsChina.

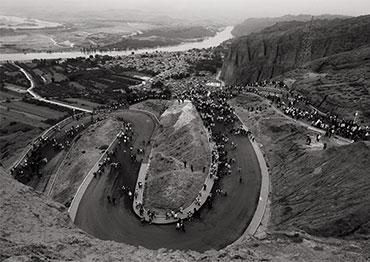

The Yellow River Stone Forest park, for example, previously hosted three ultramarathons. Media reports said that Baiyin started promoting tourism in 2008 as the mining industry had depleted the area’s mineral resources, mainly copper.

In a post on Sina Weibo, Xu Keyi as she identified herself on Sina Weibo, who has helped organize more than 10 ultramarathons, expressed her doubts as to whether the region was suited for such races, though most professional ultramarathoners consider the Stone Forest race below average in difficulty. “There are no shelters between checkpoints two and four, and the runners would be between a rock and a hard place at checkpoint three, so they should have provided more safety measures at checkpoint three,” she posted.

“They managed to hold three [successful] races, but that might have been sheer luck... Extreme weather should be taken into consideration when holding a cross-country race in such a region,” she added.

According to Wei Bi, most extreme endurance races in China are run by small companies that generally lack experience and want to keep costs low.

According to Shangyou News, a news app run by the Chongqing Daily, Gansu Shengjing Sports only had around 22 employees. Many of the on-site personnel were temporary workers.

Despite its small size, the company, established in 2016, had won the bids for the Stone Forest races for four consecutive years, each worth around 1-1.5 million yuan (US$156,300-234,500).

The news sparked heated discussions, where many alleged the local government and the company had engaged in shady deals and kickbacks. However, no official source has addressed these allegations. Journalists have not been able to contact the company.

“Given ultramarathons are less popular... governments don’t have enough of a budget and generally dedicate around 1 million yuan (US$156,300). But this isn’t enough,” said the manager of a longdistance race organizing company who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “Local governments have a tendency to give the race to the lowest bidder and they won’t necessarily check whether the operator is reliable,” he told NewsChina, revealing that in recent years, less-developed or even poverty-stricken regions have held marathons in the hopes of attracting investment and tourism.

The manager said that many organizers and operators hold longdistance races despite not having the proper resources. “Compared to regular marathons, ultramarathons are much more difficult to organize and operate, three to four times more difficult,” he said.

“When they hold competitions, organizers should take local conditions into consideration. They shouldn’t be reckless and try to hold a 100-kilometer race [straight away]. Instead, they can start with shorter races and slowly accumulate experience to attract talented runners according to their own resources.”

Ultramarathons were unregulated in China until this April, when the CAA included a set of standards for organizing them in its latest documents for marathon management. However, experts say the new standards are too general and hard to implement. It is still unclear as to which organization officially has the authority to supervise ultramarathon races, the CAA or the Chinese Mountaineering Association.

“Long-distance races began in Europe and the US, which have accumulated years of experience in holding them and are well-equipped with supporting institutions... Some [Chinese] organizers only imported the race format while disregarding the supporting institutions and underlying spirit,” Wei said.

Old Version

Old Version