hen I was teaching journalism at the Communication University of China, a student met me during office hours to show me a sentence I shall never forget.

It was 130 words long, with clauses strung together by almost every connecting word in the English language.

It had more “whereas” and “heretofores” than an End User License Agreement.

I told him it was the longest English sentence I had ever seen, and he beamed with pride.

He was preparing for the GRE, and had been told that the longer sentences he writes, the higher score he would receive.

This was easy for him to believe, because in Chinese writing, long florid sentences are a sign of culture and erudition. Chinese prose has an almost Dickensian flow to it, as if the writers are paid by the word, with bonuses if the reader needs to look things up in the dictionary.

In Chinese, extended or poetic metaphors are as valued by readers as fine liquor is treasured by poets.

If Chinese writers want to shine like a crane standing in a flock of chickens, they will wedge as many stock idioms into their writing as possible.

For extra effect, they make subtle allusions to historical figures and literary tropes to add layers of meaning and persuasion, much as TS Eliot sprinkled his poems with classical references.

I explained to my student that all of these tendencies are discouraged in modern English news and business writing. Writers from Shakespeare to Melville employed these devices to great effect, but ever since the era of Hemingway, writers prefer short clear prose with active verbs and a minimum of adjectives and artifice.

Today’s concept is that the writing should not draw attention to itself, creating space for the ideas you want to convey to shine through.

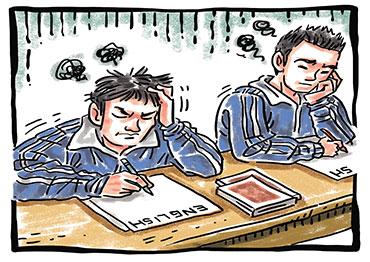

Chinese native speakers have a hard time truly accepting this. Most would agree that “When in Rome, do as the Romans do,” but writing simple short sentences is a bridge too far, making them feel childish and simple – much as they may secretly judge modern English writing to be.

This explains many of the quirks that betray writing by Chinese who learned English as a second language.

Like a student trying to impress a teacher, their sentences tend to be far too long and complex.

Not only are there too many uses of connecting words like “but,” “and,” and “besides,” but these words are often used incorrectly.

The logic behind words such as “but” and “because” in Chinese is looser and works differently than in English.

My journalism students used to talk about “Chinese logic,” and indeed the line of reasoning demanded by the two languages takes a different path when it comes to conjunctions.

That means in many cases, a native Chinese speaker will use a connecting word incorrectly, causing more confusion than clarity.

In modern English, writers are almost always be better off deleting conjunctions, making two sentences whose ideas logically flow into each other. This way, a clear line of thought does all the work, putting conjunctions out of a job.

This is not easy, as it demands a writer to actually understand what they are trying to say – a rarity in any language.

One of the fascinating things about learning a new language is learning a new way of seeing the world. This is sometimes reflected in the way the same words have different meanings and nuances.

For example, Chinese students leave university and “join society,” but English students simply graduate and “join the workforce,” since they were part of society the whole time.

To Chinese, society is a concrete thing that people actively build, an idea similar to “civilization” in English.

But “civilization” is another word that doesn’t translate well. Signs in front of urinals throughout Beijing suggest that taking a small step forward before doing their business will be large step forward for “civilization.”

“Civilization” here means having thoughtful manners and civil conduct.

Differences in the political and economic systems in China holds special challenges. Art and music become “cultural products,” created by “culture workers” rather than artists and musicians.

Pursuing environmentally friendly policies is “constructing a green society.”

A catchphrase like “moderately prosperous society” will resonate on several levels of meaning for a Chinese speaker, with roots in both China’s reform and opening-up process and ancient Chinese thought.

However, the phrase will leave uninitiated English speakers puzzled, asking themselves, “Why not aim for a prosperous society? Surely that would be a more enticing aim.”

Using shorter sentences, avoiding conjunctions, and being aware of similar words having different meanings are the “two bigs and one little” of errors I often encounter when editing native Chinese speakers, but there are of course too many quirks in the way the languages are used to be covered in one article.

Old Version

Old Version