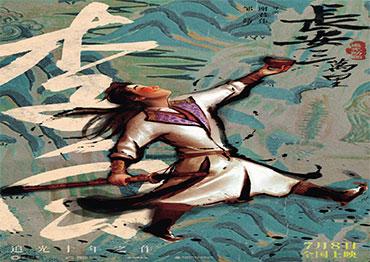

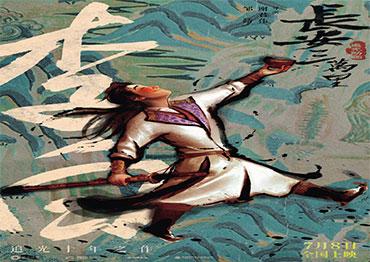

Twenty years later in 742, Li finally found a patron. Through a well-connected friend, Li presented his writings to Emperor Xuanzong in Chang’an. The emperor took a great personal liking to Li, and granted him a position at the Hanlin Academy, an elite institution that provided the court with scholarly and literary services.

During his time in Xuanzong’s service, Li wrote many poems complimenting the beauty of the emperor’s favorite concubine, Yang Guifei. But in a drunken gaffe, he asked the court’s most powerful eunuch, Gao Lishi, to help remove his boots in front of the emperor. Gao was furious. In revenge, Gao persuaded Yang Guifei to take offense at Li Bai’s poems about her. Emperor Xuanzong dismissed Li from the imperial court in 744, but not without a generous severance of gold and silver.

After leaving Chang’an, Li found religion. A student of Taoism since his youth, Li officially became a Taoist after enduring a physically challenging ritual witnessed by friends. In the autumn of that year, he met the poet Du Fu. The two connected over a shared love of poetry and wine, and lived together for a time.

It was through Du Fu that Li met Gao Shi, the co-star of Chang An. While the decades-long friendship between Li and Gao began in their 40s, Chang An takes a liberty by portraying the two meeting in their 20s, perhaps to maintain the interest of younger moviegoers. For the next 10 years, Li continued to travel the country, writing poems and meeting with friends along the way. It was during this period that he penned the timeless classic “Invitation to Wine”:

Do you not see the Yellow River come from the sky,

Rushing into the sea and never come back?

Do you not see the mirrors bright in chambers high,

Grieve over your snow-white hair though once it was silk-black?

When hopes are won, oh! Drink your fill in high delight,

And never leave your wine-cup empty in moonlight!

Heaven has made us talents, we’re not made in vain.

A thousand gold coins spent, more will turn up again.

Kill a cow, cook a sheep and let us merry be,

And drink three hundred cupfuls of wine in high glee.

Dear friends of mine,

Cheer up, cheer up!

I invite you to wine.

Do not put down your cup!

I will sing you a song, please hear,

O hear! lend me a willing ear!

What difference will rare and costly dishes make?

I only want to get drunk and never to wake.

How many great men were forgotten through the ages?

But great drinkers are more famous than sober sages.

The Prince of Poets feasted in his palace at will,

Drank wine at ten thousand a cask and laughed his fill.

A host should not complain of money he is short,

To drink with you I will sell things of any sort.

My fur coat worth a thousand coins of gold

And my flower-dappled horse may be sold

To buy good wine that we may drown the woe age-old.

(Translated by Xu Yuanchong)

But the good times would not last. In 755, the An Lushan Rebellion erupted. An Lushan, a Tang general, declared himself emperor in northern China by establishing the short-lived Yan Dynasty (755-763) and even seized the capital Chang’an for a time.

Though eventually quashed, the rebellion, which spanned eight years and the reigns of three Tang emperors, shook the most glorious empire in Chinese history to its core.

During the chaos, Emperor Xuanzong’s 16th son, Prince Yong, made an attempt to occupy regions south of the Yangtze River. Seeing his chance to fulfill his political aspirations, Li joined the prince to become his poet laureate. But the prince was accused of treason in 756 and executed the following year. Accused of guilt by association, Li was arrested and imprisoned.

In 758, Li was exiled to Yelang, a city on the western fringes of the Tang empire in present-day Guizhou Province. He stopped for prolonged visits with friends on the way, leaving poems with detailed descriptions of his long journey.

Meanwhile, things were not going so well back in Chang’an. The empire was suffering from a severe drought that threatened the Tang’s grip on power. Emperor Suzong, who reigned from 756-762, offered general amnesty for all convicts. This was a protocol among emperors during natural disasters, as it was believed the act of mercy would curry blessings from heaven.

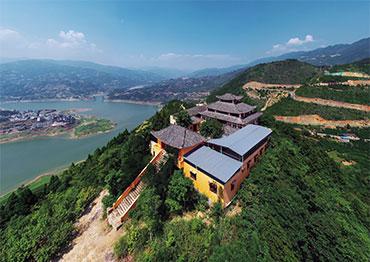

Li was pardoned before he arrived in Yelang. Regardless of whether the emperor’s order pleased the heavens, Li was elated by the news, and composed the poem “Leaving the White Emperor City at Dawn” to express his joy in returning home:

Leaving at dawn the White Emperor crowned with rainbow cloud,

I have sailed a thousand miles through Three Georges in a day.

With monkeys’ sad adieus the riverbanks are loud,

My boat has left ten thousand mountains far away.

(Translated by Xu Yuanchong)

Li eventually made his way to Dangtu, now Dangtu County, East China’s Anhui Province, to live with a relative, where he passed away in 762. He was 61. Legend has it he drowned in the Yangtze River, falling from his boat while trying to embrace the moon’s reflection – while drunk, of course.

In a final bit of irony, Li realized his political ambitions in death. The next emperor, Daizong, issued a decree in 764 appointing him as his counselor, unaware that Li had already been dead for two years.

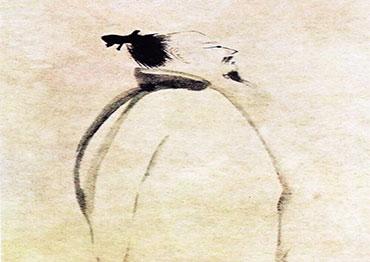

Li lived as he wrote – unbridled. He married four times. His first and third wife died, he left the second one, and was separated with his last wife during exile, never to see her again. He had altogether two sons and one daughter with the first wife and the third wife, but never settled down to raise them. He came from wealth, but preferred life as a vagabond. He gambled in politics, and always fell on the losing side.

His poetry reflects this undulating spirit: he can be lyrical or descriptive, wildly celebratory or somber and self-reflective. It is these contrasts, and the universal emotions he so elegantly captured in a wine cup, that make his poetry immortal.

Old Version

Old Version