hree decades ago, American historian Patricia Buckley Ebrey released a groundbreaking work on women in Chinese antiquity that is still finding relevance in the country’s gender politics.

Among the more unexpected examples involves the ongoing debate over strong female characters in Chinese TV shows set during the Song Dynasty (960-1279).

The Story of Ming Lan from 2018, for instance, centers on a self-empowered woman and her choices in love, marriage and life. Another example is last year’s hit A Dream of Splendor, which follows a group of independent women who build their own teahouse business.

Many critics argue that such characters were unlikely in the Song, a dynasty known for foot-binding and other feudal inequalities for women.

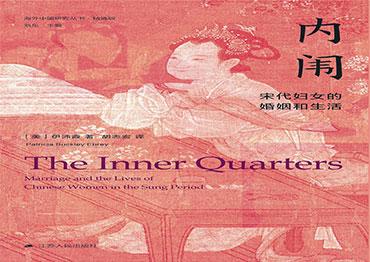

But in The Inner Quarters: Marriage and Lives of Chinese Women in the Sung (1993), Ebrey argued that women of the dynasty were not the “silenced victims” of patriarchal structures as described in traditional historical narratives. Instead, they actively strove to change their fates, to varying degrees of success.

The book was among the first to focus on the history of Chinese women, and had a tremendous influence on Chinese academia.

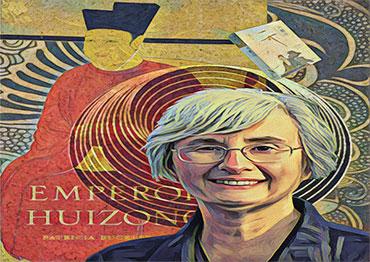

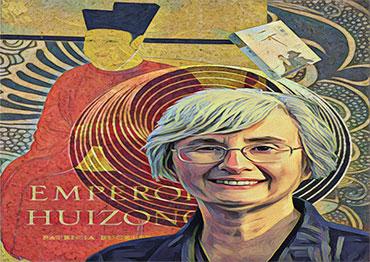

But Ebrey’s focus goes beyond women’s studies. In 2014, her biography Emperor Huizong recast the Song emperor, long regarded as a decadent, political failure, as an ambitious ruler who died tragically in pursuit of glory for his realm.

In March 2023, a new Chinese-language book, Delving into Ancient China, Patricia Ebrey’s Studies on Ancient Chinese History was published by Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House. Edited by five Chinese scholars, the book compiles 11 of Ebrey’s translated papers, tracing her academic findings over the past five decades.

The 76-year-old professor emeritus at the University of Washington in Seattle talked with NewsChina about women of the Song, gender dynamics and developments in contemporary women’s issues.

NewsChina: When you started your academic career, you focused on the Chinese aristocracy of the Middle Ages. Why did you switch to the history of women? Were you influenced by social trends and changing mindsets in the US during the 1960s and 70s?

Patricia Ebrey: When I picked my dissertation topic, I wanted to do social history, that is, to see the changes in the structure of society, who had power and how they maintained it, and the like. I did not want to focus just on those at the top of the government, but look at the broader elite class. I was also interested in the significance of family in the elite and read quite a bit by anthropologists about family and lineages in China in the 19th and 20th centuries. My advisor was a Han period (202BCE-220CE) specialist, so I began from the Han period but carried it through to the end of the Tang (618-907).

After I finished that book (Aristocratic Families of Early Imperial China: A Case Study of the Po-ling Ts'ui Family,1978), I moved into the Song to be able to go more deeply into the history of family and kinship in China, aware that Song sources were much richer for the topic. Through much of the 1980s I was working on topics related to family and kinship, including property law and family rituals, such as weddings, funerals and ancestor worship.

Of course, beginning in the 1960s, the women’s movement was quite active in the US and it had a general effect both on how we pursued careers and the sorts of questions we found intellectually compelling. Already when I was in high school, Betty Friedan’s 1963 book The Feminine Mystique was being talked about. Young people questioned notions of what was natural and appropriate for men and women. Were men really more suited to management jobs because they had played team sports in high school or served in the military and thus knew how to work together? What pressures made girls in high school focus so much on their clothes, hair and how others judged their looks? To change these mindsets required “consciousness raising,” which often involved women getting together and talking about the forms of sexism they observed and what could be done to change the system.

When I was in graduate school, there were quite a few women graduate students in my department. We thought our professors, all men, had many strong points as scholars but did not really take us seriously, assuming that as soon as we married and had children, we would give up academic ambitions. We thought that we should not argue with them but simply persist in doing good work. People did suggest that one should not do a dissertation on women’s history because it wouldn’t be taken as really equivalent to the serious subjects men were writing about. The idea was to do something standard first, to establish one’s credentials. Then, if one wanted, one could do something in which women figured more prominently. By the mid 1980s, this had changed and more women were working on women’s history, even as initial projects.

In my own case, I was influenced by colleagues in the history department at the University of Illinois who were working on women’s history of the US or Europe. I introduced a course on women and the family in Chinese history that went up to modern times. My students and I were especially taken with a documentary made by Carma Hinton, who had grown up in China, called Small Happiness, which interviewed several women, some still with bound feet. Before long I wrote a book in which women were the central topic (The Inner Quarters).

NC: In your article “Women, Money, and Class: Ssu-ma Kuang and Neo-Confucian Views on Women,” you claim that women were not pure victims of the system, but rather perpetuated the system onto others. Do women actively take part in harming the overall status of women?

PE: I tried to keep in mind that the woman who had been treated poorly as the new bride by her mother-in-law might well feel it was her turn to have someone to boss around when she got a daughter-in-law herself. I think that this is a rather common human phenomenon, which we can see in other societies and social groups. In the case of the Chinese family, although men definitely had more power than women, the older generation, both men and women, had considerable power over the younger. I didn’t want to portray women simply as victims but show that they also positioned themselves to benefit from the system when they could. It is the system we should notice.

NC: You once observed that women will compete more with other women in a society where they face more restrictions, now known as female intrasexual competition. Often when a husband cheats, the wife will attack the mistress instead of the husband. In Chinese TV and movies, friendship between women is often depicted as shallow and not as sincere as that between men. Why?

PE: I do not doubt that rivalry among women and unpleasant, even nasty behavior toward other women was far from rare in families like the one portrayed in the novel Dream of the Red Chamber, complex ones with brothers and their wives and concubines all living together, perhaps with a grandmother holding significant power. In Song sources, one often sees mistreatment from the other side: the frequency of praising a woman for her generosity toward the maids and concubines, or the claim that she was not at all jealous. This implies that many are jealous and do not treat the maids and concubines very well.

Today women are rarely in competition within the home because households are generally quite small and do not include concubines, so today’s complaints are mostly about women in the workforce or ones involved in marital disputes.

I can say something about relations among women at work from my own experience. It is true that scholarship is intrinsically competitive – people judge one another’s work all the time. But I never felt that I was competing specifically with other women for jobs, promotions, grants, book contracts or the like. Perhaps because we knew the stereotype that women tend to be competitive with other women, I think my generation of female scholars committed ourselves to not acting that way, but rather trying to support each other and make things better for the women coming after us.

Things could be different today. When I was starting out in faculty positions in the 1970s at the University of Illinois, there were few women senior to me but a handful who were more or less my peers. Men were the large majority in the two departments I was associated with (history and Asian studies), and the tiny minority of women felt comfortable talking with one another. We talked about lots of issues relating to how to survive in a male-dominated world.

We knew of women of the prior generation who used their initials rather than their first names when publishing so that readers would not be able to detect that the author was a woman, for fear that they would dismiss their work without reading it. My peers and I argued to the contrary that we should use our names so that younger women would see that women can also publish solid books and articles. We also talked about how important it was not to ask for any special favors. After all, when I started out, women in New York City were demanding to be allowed to become firefighters, saying they could carry anything men could carry through blazing fires. Surely we shouldn’t ask to skip a meeting just because we had children at home. After all, we were claiming that we were as able to do the job just as well as men.

Here I have been talking about interaction with colleagues in my departments, people I would see regularly. There is also the much less frequent interaction with scholars in my field across the country, people who might read what you write but you see only at scholarly meetings. In this context, I always felt women tried to look after each other. Last year when one of the early scholars in Chinese women’s history, Charlotte Furth, died, a few of us got together to reminisce about her. The most common comment was how much she tried to encourage younger women scholars in the field.

NC: How can we apply research about women in history to better understand women’s issues today?

PE: Understanding that women’s situations have varied considerably over time and place counters the assumption that it is above all biology that determines the shape of women’s lives. Thus, I think cross-cultural studies are just as interesting as ones that look at change over time. Anthropologists did this first, showing that women fared differently in matrilineal societies than patrilineal societies, for instance. But historians were soon also showing that there have been changes over time in such things as the size of households, age at marriage, where new couples lived, the impact of moving to cities, and so on, all of which had an impact on women’s lives.

I suspect that for young women in China today it is just as interesting to learn more about women’s situations in other countries as in China a thousand years ago. But by considering women in the Song, they can think about some of the issues we have been discussing, like women’s competition with each other, women spending their days primarily with other women, the importance placed on having sons, how women’s situations change as they get older, the difference class and education make, and the like.

Old Version

Old Version