For many Chinese experts, the significance of the BRI goes far beyond trade and investment. “The most significant achievements of the BRI lie in its exploration of alternative development patterns and international economic cooperation models,” said Wu Huimin, managing director of the Global Institute (CGI) of China International Capital Corporation (CICC).

Wu told NewsChina that with its infrastructure capability and proactive approaches, China has not only facilitated infrastructure development, but by opening its vast market to partner countries, it has made global trade conditions favorable for developing countries, and its growing innovation capabilities also help drive technological progress in the developing world.

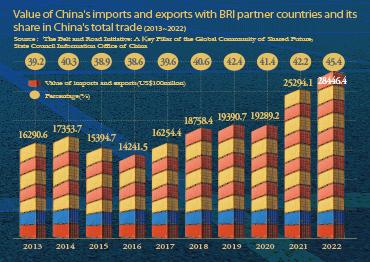

“With better trade ties and better connectivity, China’s trade with partner countries has evolved from importing raw materials to expanding into industry-specific value chains and finished product trade with these countries,” Wu said. “The expansion of potential markets in various countries has not only increased export demand but also improved resource allocation efficiency through competition.”

Another key highlight of the BRI is that it brings together a wide range of bilateral and multilateral cooperation platforms and mechanisms, Wu added. Under the BRI framework, China and partner countries have launched more than 20 multilateral dialogue and cooperation mechanisms in a wide range of fields.

Wu’s view was echoed by Wang Wen, a professor and executive dean of the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at the Renmin University of China in Beijing. In an October 3 opinion piece published in Pearls and Irritations, an Australia-based public policy journal, Wang said developing countries had regarded the so-called “Washington Consensus,” which advocates privatization and ffnancial liberalization, as the only development path, but the BRI has offered them an alternative.

“The achievements of 10 years of the BRI show that the Chinese economic experience, which champions ‘infrastructure first’ is more suited to up-and-coming countries,” Wang said. Based on the logic of what Wang dubbed “BRI Economics,” China provides loans to partner countries to build infrastructure such as railways, highways and ports. Although some projects may not be profitable in the short term, the government can still repay debts under the sovereign guarantee as these projects reduce economic transaction costs, improve economic activities’ efficiency, and drive up the value of land and real estate.

Addressing the criticism of alleged “debt traps” in Western media, Mao Ning, spokesperson of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, said at a regular press conference on March 28 that despite China’s increasing level of lending to developing countries, multilateral financial institutions and commercial creditors still account for more than 80 percent of the sovereign debt of developing countries according to World Bank statistics. To address the debt problems of relevant countries, Mao said: “It is imperative that these institutions participate in debt treatment guided by the principle of joint actions and fair burden-sharing.”

Mao stressed that in Africa alone, China helped build and upgrade more than 10,000 kilometers of railways, nearly 100,000 kilometers of roads, nearly 1,000 bridges and nearly 100 ports, which has contributed to these countries’ economies and peoples’ livelihoods and delivered tangible benefits to local communities.

“To date, none of the partner countries have accepted the claim that the BRI has created ‘debt traps,’” Mao said. “On the debt issue, developing countries know best from their own experience who is a sincere and reliable friend and who is a rumor-monger with ulterior motives.”

Among the most frequently cited cases involves China’s investment in infrastructure projects in Sri Lanka, including Hambantota Port. According to the narrative in Western media, the Sri Lankan government had to enter into a 99-year lease contract to a Chinese company to repay the country’s colossal borrowings from Chinese banks for the port construction.

Yet several reports, including one published by The Atlantic in February 2021 titled “The Chinese ‘Debt Trap’ Is a Myth,” found that when the port was leased to China in 2017, loans from Chinese banks accounted for less than 5 percent of the country’s total debt service that year. Moreover, the loans involving the port were not in default then, and the proceeds from the lease were not to repay loans owed to China but to bolster Sri Lanka’s own foreign reserves.

In a July interview with CNA, an English-language news network in Singapore, Sri Lankan Foreign Minister Ali Sabry dismissed the debt trap narrative, and stressed that China’s investment is “very, very important” for his country’s growth. According to China’s recent BRI white paper, the annual throughput of bulk cargo at Hambantota Port has reached 1.21 million tons.

Old Version

Old Version