rom the adventurous travels of Marco Polo to the analytical musings of Voltaire and Leibniz, European figures have sought to understand China since the mid-13th century. These literary and philosophical giants approached China with a mix of awe and curiosity, their perceptions shaped by direct encounters and secondhand accounts.

Their perspectives are presented in the 2022 book China Through European Eyes: 800 Years of Cultural and Intellectual Encounter by Kerry Brown, a professor of Chinese studies and director of the Lau China Institute at King’s College London.

“At the heart of this European understanding,” Brown writes, “has been how best to manage this sense of ‘difference’ – to see it, broadly, as something inspiring, stimulating and to be embraced, or as something threatening, intimidating and to be countered.”

“This sharp clash of attitudes continues to the present day, which is why looking at the roots in the past is helpful even in a contemporary situation,” Brown said.

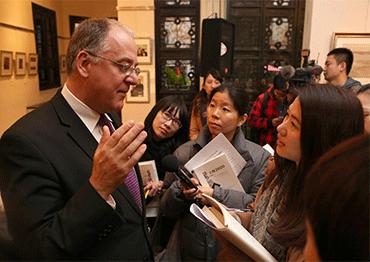

In a written interview with China News Service in early June ahead of the World Dialogue on China Studies • Belgium Forum, Brown shared his insights on how historical understanding can enhance modern China-Europe relations.

In his message to the forum, Brown expressed concern that European scholars today face challenges similar to those of their predecessors – ideologically driven, polarized perceptions of China fueled by anxiety over Europe’s stability and global position. The lack of a robust ecosystem and inclusive public discourse to support China studies in Europe has led to a dichotomous view of China as either a cultural threat or an untapped market.

Held on June 20, the forum gathered around 60 scholars and experts to discuss “China Studies and the European Understanding of China.” The event was co-organized by the Shanghai Municipal People’s Government Information Office and the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, with support from the European Institute for Asian Studies, Madrid-based non-profit Cátedra China and the Brussels Chinese Culture Center.

China News Service: What first sparked your interest in China and the development of China-EU relations? What are some of your most significant projects in the field?

Kerry Brown: I first went to China while based in Japan in 1991 [as a high school teacher]. I went back to live and work in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region from 1994 to 1999 after learning Chinese. From that time, researching China’s history, politics, culture and society has remained central to my life and career. China offers a hugely complex, interesting and rewarding history, literature, culture and world view, and one where I often find commonalities as well as differences with my own.

The dialogue in my life between my own experiences as British, a European and a Westerner, but learning about China, has made it very different from what it might have been had I remained restricted to the cultural outlook of a European.

I was a diplomat working from 2000 to 2003 as first secretary at the British Embassy in Beijing. Over that period, I managed to visit every single province and autonomous region in China, including Xinjiang, Tibet and Hainan.

I subsequently worked as head of the Asia Programme at Chatham House (The Royal Institute for International Affairs) in London, and then as professor of Chinese politics and director of the China Studies Centre at the University of Sydney in Australia.

Since 2015, I have been professor of Chinese studies at Kings College London. Specifically, on the EU and China, from 2010 to 2014, I directed the European Chinese Research and Advice Network (ECRAN), giving policy advice to the European External Action Service (EEAS). That allowed me to have access to thinking and ideas about what the policy position of Europe should be toward China, at a key time when a great deal was discussed about an effective relationship with China.

CNS: What is your assessment of China studies in Europe?

KB: At present the field of China studies is highly politicized. And in the past decade or so the research environment has seen more difficulties, partly from Europe, such as the rise of nationalism in Europe, the political turmoil and US influence. At the same time, Covid-19 cut off normal people exchanges and there has been a lack of opportunities to visit China by relevant Europeans. Even though face-to-face events and visits are gradually coming back, they are still far from reaching the pre-Covid level. At the moment, Chinese students and scholars coming to Europe by far outnumber Europeans going to China.

CNS: You have said that engaging with and understanding China was once optional, but for people in the 21st century it has become a necessity. Can you elaborate on this?

KB: China is an inevitable part of geopolitics today, particularly because of the importance of its economy, and the fact that Chinese people will be the key players in shaping the global future through their economic and life choices. In combating climate change, in dealing with the challenge of AI, and in trying to make a more prosperous, peaceful world, China has to play a role in this, and has huge amounts it can contribute. The main challenge is to create the right geopolitical framework by which to do this in a stable, manageable and balanced way.

CNS: What inspired you to write China in European Eyes at that time? How does the book present Europe’s narrative of China? What other details impressed you?

KB: Europeans have a long history with China, dating back at least to the time of Marco Polo in the Song and Yuan dynasties (960-1368). In the Ming and Qing (1368-1911) eras, Italians, Germans and the British were dealing with China as missionaries, traders and travelers.

I felt it important that Europeans have at least some awareness of this history, because it is often obscured or forgotten.

In particular, since the Enlightenment, figures in the 17th and 18th century like the philosophers Leibniz, Voltaire and Montesquieu all wrote about and thought about China, but in very different ways. Reminding ourselves of their work today helps to understand why Europe often has the very ambiguous views toward China.

Leibniz was the person who tried to understand China in its own terms, through studying Confucianism and the meritocratic bureaucratic system of governance then. Voltaire in his early career largely compared China in a way which was quite favorable with Europe, and idealized the place. Montesquieu tended to be very critical of what he labelled a form of Chinese absolutist governance and despotism. One can argue that all these positions were distortions, but at least till today those strands of slightly idealizing or demonizing China remain.

My aim in compiling this book was to put in one place the key texts of these and other key Europeans like Hegel, Weber, Marx and Russell, and what they wrote about China, so we could remind ourselves of how long and deep European engagement with China has been, and also try to create our own narrative of what we feel and think about China.

CNS: Given these issues, what are the most important things China and Europe should cooperate on?

KB: China and Europe have to deal with each other, particularly on transnational issues. And on many issues, in terms of the underlying situation, they largely agree. Europeans need to think more about what they want from China, and where they can best cooperate, and of course Chinese need to do the same.

There is a great difference between the two, in terms of the fact that China is a sovereign state, and Europe a collection of single states, some in the European Union and some not. But that diversity gives Europe some great advantages in terms of pluralism and diversity. China and the Europeans have a deep, longstanding knowledge of each other, and huge people-to-people links. They can deal with challenges with each other, even though at the moment the relationship is a difficult one because of geopolitical issues.

CNS: How can China and Europe bridge their differences in the future and further deepen understanding, mutual trust and cooperation?

KB: They need to remember how much history they have with each other, and focus on issues like global warming, AI and other transnational challenges, where there is much common ground and already a good basis. Europe needs to strive for at least some strategic autonomy from the US in its relations with China, even though its security relationship with China is very important.

Everyone needs to remember that the story of China today is about the lives of 1.4 billion people, many of them living in ways unimaginable even 40 years ago. The raising of living standards in China, and the better material standards for the lives of many Chinese people, is perhaps the greatest single contribution to human well-being in the modern era, and perhaps in human history. That part of the story of China keeps on being forgotten, but we need to constantly remember it. It matters!

Old Version

Old Version