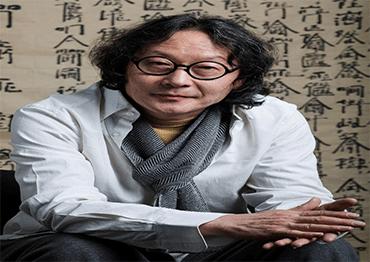

In my work, the separation between the classical and contemporary does not exist. In its essence, the separation between the East and West also does not exist. These are the attitudes my work expresses,” Chinese artist Xu Bing said during his exhibition A Moment in Time at the American Academy in Rome on May 29.

Xu had responded to a question about how his latest piece, “The Wall and the Road,” compares to his previous body of work, which draws on the tensions between tradition and innovation.

Commissioned for the Rome exhibition, “The Wall and the Road” features his rubbings from the Great Wall of China and the ancient Appian Way in Rome. Xu described it as “a conversation between two important ancient civilizations.”

Communication is the core idea in Xu’s work, bridging East and West, antiquity and modernity, and even Earth and outer space.

On February 3, the satellite SCA-1 was launched into orbit off the coast of Yangjiang, Guangdong Province aboard a Long March 3B carrier rocket.

The SCA-1 is the first “art satellite” of the Star Chain of Arts Project. Led by Xu Bing Studio and Beijing Wanhu Chuangshi Cultural Media, the project invites artists worldwide to use images from the SCA-1’s camera through the Xu Bing Art Satellite Creative Residency Project.

One notable outcome of this project is “Satellite Lake Cosmic Reflections,” Xu’s animated short exhibited at his show Xu Bing: Art Satellite – The First Animated Film Shot in Space at the Church of Santa Veneranda in Venice, Italy from April to July.

The work features an animation played on a screen on board the Lady-bug-1 satellite. Launched from Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in Gansu Province in December 2018, Ladybug-1 was previously a logistics satellite developed by Beijing-based Commsat. It is now repurposed as part of the Star Chain of Arts Project.

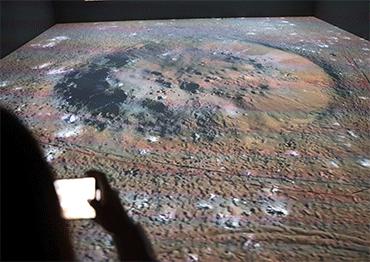

Ladybug-1’s external camera videos its screen playing the animation, which is beamed to Earth in real time. The feed is then projected on the ceiling of the gallery, which shows the looping animation playing on the satellite’s screen with the Earth in the background.

In an interview with China News Service, Xu delved further into his views on combining space technology and art.

China News Service: How did you conceive the idea of using space technology in your art and hosting an exhibition in Venice?

Xu Bing: We chose to hold the exhibition at the Church of Santa Veneranda in Venice, which is still in use [as a place of worship]. The church features an elevated white vaulted ceiling. We project the animated movie shot in outer space on the ceiling and slowly rotate it, and viewers watch it from easy chairs and cushions on the floor.

Interestingly, while prayer and worship occur on the other side of the church, this seems to be a special closed space where viewers can lie down and look up at the starry sky, and the whole environment and the work itself forms a new artistic expression.

This work is part of the Space Art Project, which began six years ago. At the time, Yu Wende [founder of Wanhu Chuangshi] approached me with an offer to launch an “art rocket” for artists. I didn’t have much interest in this idea, because I didn’t like that kind of grandiose stuff, though I was intrigued by how space technology could contribute to art creation. I was much more interested in the things around me in everyday life. But later I did some research, and found it a field worth exploring.

After all sorts of preparations, we finally launched the first “art rocket” three years ago [called Book from the Sky, the launch failed]. At that time, people didn’t understand why I was putting so much effort into space art, which sounds like a pie in the sky idea. But I realized the potential in this growing area. As interest in space is increasing, people feel closer to space technology and outer space. Significant advances in space science and the techniques for artistic expression open up new opportunities. The development of China’s private aerospace companies expands the possibilities.

CNS: You have often emphasized the importance of the “social scene” – social phenomena or realities of daily life – for artistic creation. How do you draw motivation and inspiration from it?

XB: I always keep a close watch on the social scene, which offers much to reflect on and express. This reflection is an ever-deepening process, where neither inspiration nor a response to any new phenomenon occurs immediately.

The internal logic and deeper reasons behind new phenomena need to be explored slowly and gradually. In art creation, this means that a project requires constant digging [into the causes and factors behind such phenomena]. During this process, we may find that the causes and factors themselves behind a phenomenon are also mutating and developing, making my artistic creation a never-ending process.

If an artist is sensitive, they can figure out the internal logic behind these phenomena, generating new inspiration for humanity’s understanding and thought patterns, and even their assessment on where civilization is heading.

CNS: Your works showcase your avant-garde ideas, from Book from the Sky to film Dragonfly Eyes, which features surveillance camera footage. Does this indicate a consistent and deliberate exploration of art boundaries and forms?

XB: It’s not really deliberate exploration. Expanding boundaries and forms is a natural mission of art. Unlike contemporary art, which is supposed to have a style and a genre, many of my works do not have a fixed or clear style. The essence of contemporary art lies in the thinking and attitude behind the works. This is the value that contemporary art provides to people and the world.

I often say that if an artist wants to maintain creativity, they shouldn’t take existing knowledge or the established art system too seriously. Focusing too much on a specific art system hinders creativity because the system has been intellectualized and made systematic. Instead, you should pay attention to what’s outside the art system and the ever-changing social scene. If an artist knows how to transform the creativity and energy of the social scene into a source of inspiration, they can keep up with the times and create endlessly.

CNS: You previously mentioned that you want to create works that are approachable for the public rather than overblown and empty. What makes art approachable, and why should it be?

XB: Having created contemporary art in Western countries, I am dissatisfied with the barrier and gap between Western contemporary art and the public. Art critics explain art with words, but the more they explain, the further they push the audience away. Many works intimidate the audience or make them feel inferior, with so-called contemporary art having a special status. This suggests they don’t understand art, need more art education and don’t have an artistic sensibility. But we haven’t reflected on the problem of the contemporary art system itself, which creates a huge gap and disconnect with the public.

Back in the 1990s, I was already upset about how contemporary artworks alienate the public. I created works like turning a gallery into a classroom for learning calligraphy, where viewers could come in and learn. They would then realize that it wasn’t Chinese calligraphy but strange-looking English characters, making it very intimate. Back then, interactive art like this was uncommon, and this was a simple method for physical interaction.

Today, with the development of technology like video, virtual reality and sensors, interactive works have become commonplace. Although my works utilize these technologies, I consciously hide them when presenting to the audience. This way they feel more approach-able, like something from their daily lives. For Dragonfly Eyes, I didn’t want to make it an experimental film. Instead, I made a genre film about an everyday love story, making it easy for the audience to understand and resonate with. The movie’s technical avant-gardeness is hidden rather than shown off.

CNS: You studied and taught in China before settling in New York. How do you view your cultural background, and how do you balance Eastern and Western expressions in your art?

XB: Traditional Chinese culture profoundly shapes my cultural makeup. My generation grew up when China began its reform and opening-up, emphasizing on learning from the West’s advanced culture. Therefore, we have experience utilizing Western culture, but less so our own traditional culture. Our generation’s cultural makeup is so complex that we ourselves don’t entirely understand it.

My works touch upon multiple cultures, yet I don’t deliberately balance Eastern and Western influences. This has to do with my own background and the deep traditional culture that all Chinese inherit. This cultural root has played a vital role in my international engagement.

When working internationally, cultural makeup is indeed very important. A work that draws attention in the international art world often does so because the artist is bringing qualities of their culture to the international art scene. In a broad cultural environment, if you offer something missing there, your creation becomes valuable.

CNS: You were appointed Hong Kong’s Ambassador for Cultural Promotion in March. What are Hong Kong’s cultural features and strengths?

XB: As a Chinese mainland artist who engaged with Hong Kong’s cultural circles early on, I found that Hong Kong did a great job in realizing art for the people. Various arts such as opera, symphonies, art museums and folk art are part of daily life in Hong Kong. They are not exclusive and are easily accessible.

Hong Kong boasts mature and high-quality education. Many of its artists have studied in Europe and returned to create contemporary art, which is valuable and amazing.

CNS: Upon your appointment, you expressed a desire to nurture Hong Kong’s young artists. Could you elaborate? What qualities and weaknesses have you found in the city’s young artists?

XB: There are many programs. For example, during my two-month residency at the American Academy in Rome, Hong Kong sent four young art students to participate in a new program. This effort aimed to nurture young art talents in Hong Kong.

The Art Satellite Creative Residency Project is now open to artists worldwide, including Hong Kong’s young artists and universities. Hong Kong excels in tech art, so I hope for more cooperation in this area in the future.

Hong Kong’s young artists have received a comprehensive and diverse education with a global vision, ensuring a sound academic foundation. They are hardworking, earnest and have a strong sense of responsibility. All this is fairly good. As Hong Kong enters a new social process, this will broaden their artistic horizons and enhance their understanding of the art-society relationship.

Old Version

Old Version