NewsChina: You said that China’s protected areas system is challenged by problems of overlapping boundaries, unclear boundaries, unclear powers and responsibilities, and major contradictions between protection and development. What caused these problems?

Wu Bihu: Before the restructuring of government ministries in 2018, management of the protected areas system came under the former Ministry of Environmental Protection, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, the State Forestry Administration, the Ministry of Water Resources, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, the former Ministry of Land and Resources and other departments. Each department had their own policies and established their own protected areas. Local governments also wanted to give different titles to the same protected area to solicit more financial support. For example, an application for a provincial-level forest park or national wetland park could net local authorities from hundreds of thousands of yuan to millions of yuan per year. So some local governments established boundaries for protected areas without having conducted sufficient research.

For example, many of the 244 national scenic spots previously under the remit of the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development overlapped with established national nature reserves, national forest parks and national marine reserves announced by other government agencies.

A few years after they established these areas, some local authorities found they didn’t get enough money to keep them going, and that tourism was not even allowed in those areas. They began to regret their actions. Construction inside these protected areas needs higher approval, which can take three to five years. Some local governments decided to build illegally without approval.

After the 2018 ministerial restructure, all protected areas theoretically came under the administration of the National Forestry and Grassland Administration. We still have not fully seen the effects of this change. For the moment, the problems I mentioned still exist. Because local governments compete with each other, and every province is trying to attract tourists, we still see the problem of building before they get planning permission or other necessary actions.

At the same time, due to the renewed focus on the environment and the ecology that comes from the top, local governments prioritize environmental protection and requirements are strengthened. In efforts to avoid management responsibilities, some authorities ban tourism even in areas where it should be allowed. This results in the prominent contradiction between protection and development.

NC: Addressing that contradiction, you have proposed “breaking the binary point of view between ecological protection and tourism development.” How do we attain this balance?

WB: First we must protect these areas properly, and then decide how we use them appropriately. President Xi Jinping has said that China “Should achieve the integration of ecological protection, green development and improvement of people’s livelihood.” That is to say, local residents should benefit from ecological protection to achieve these goals.

There are two main problems. First, there are no flexible protection measures adapted to different protected places; second, places that could be used reasonably are now mostly prohibited to tourists.

Previously, China’s protected area system adopted concepts introduced from the West, which divides the protected area into different zones including [strictly-protected] core zones, buffer zones [allowing limited human use], and experimental zones [examining different land-use options]. In recent years, this system has changed into the core protection zone [human activities are prohibited] and a general control zone [human activities are restricted]. Documents issued by both the Ministry of Ecology and Environment and the National Administration of Forestry and Grassland state that “human activities are prohibited in core areas,” but this is not a rational regulation and is not suited to China’s reality. According to research by the Satellite Environment Application Center of the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, as of 2015, core areas in 380 of China’s total 446 nature reserves were found to have human activities. No country, including those in Europe, Oceania and the US, bans all human activity in its core areas.

In fact, several official documents emphasize that protected areas can moderately develop natural tourism and educational tourism. For example, the Overall Plan for the Establishment of a National Park System issued by the State Council in 2017 states: “Planning and construction should be strictly controlled, and other development and construction activities shall be prohibited except for the renovation of indigenous people’s production and living facilities, natural sightseeing, scientific research, education and tourism.” As we can see, tourism is allowed. Therefore, the statement that “human activities are prohibited in core areas” is in conflict with national policies and laws.

In my opinion, the best way is to adopt specific policies to address each protected area. Every place in the protected areas system should conduct multidisciplinary research. We should not allow experts in a single field of ecological protection to formulate overall policy.

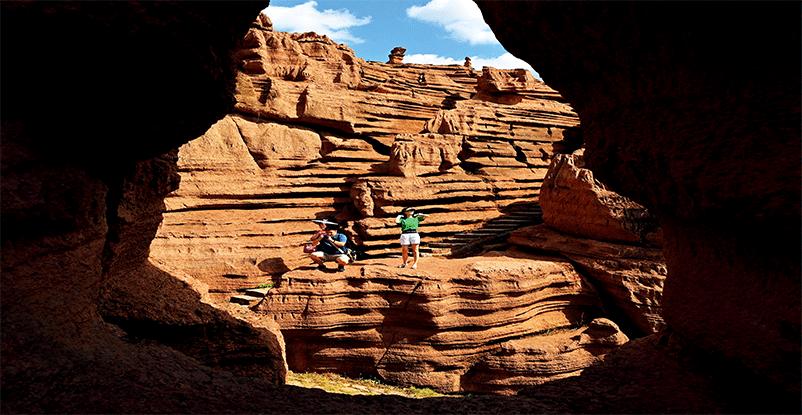

Protected areas must adopt different protection measures. For example, in geological parks with karst landforms and sinkhole crevices, human activities will not have a significant impact on the environment, so we can relax the protection of these places. In nature reserves with wildlife habitats, especially during breeding season, tourism should be restricted to minimize human impact. But in other seasons, we could designate a few months for people to go into the nature reserve to engage in photography, nature watching and other activities that do not affect animals and the environment.

So we need to study and classify different types of protected areas, and we must research and classify different human [recreational] activities. There can be different types of ecotourism activities in core protection areas, and there should be no one-size-fits-all solution.

NC: Why aren’t there individual policies for the protection and use of protected area?

WB: These individual policies for each protected area follow the US model. The establishment of our national park system refers to the US national park system. In the US, Yellowstone Park has the Yellowstone Park Protection Act, and the Grand Canyon has the Grand Canyon National Park Management Regulations.

Due to lack of financial support and lack of expertise, we do not yet have specific rules for protected areas in our country.

Now the National People’s Congress is formulating a National Park Law, and the basis of the legislation is to adhere to the unity of the three goals of ecological protection, green development and improvement of people’s livelihood. After it’s done, hopefully, we can formulate corresponding regulations which consider the differences of each national park.

NC: What do you think about the issue of unregulated hiking in Nanjiluo?

WB: First, I want to point out that the county-level forestry and grass bureau simply issued a document stipulating that no one can enter Nanjiluo, and this is just lazy decision making. It does not have any legal or rational basis.

There is a theory in environmental ethics called “wilderness education,” which means that as societies progress culturally, more people like to travel to places with few people, without a large number of service facilities and with beautiful natural scenery. That’s why we find that road trips to Xizang Autonomous Region or “secret land” travel in Yunnan are becoming more popular.

“Wilderness education” is an important step for a nation to progress culturally, learn from harmonious coexistence between people and land, and develop respect for nature. Citizens also have the right to use [a country’s] resources. I’d suggest that the State intentionally leave a number of scenic spots for the people, and that environmental agencies should guarantee public access.

NC: Since “wilderness education” is so necessary, how can a place like Nanjiluo become a regulated wilderness?

WB: To make a wilderness become a managed scenic spot, we need to have a plan. The general plan of the Three Rivers Parallel National Scenic Spot, where Nanjiluo is located, was compiled in 2005. It’s obviously not suited to the situation today, when there is more demand for self-drive travel, hiking and wilderness education. Where tourism is allowed, it is rather haphazard. They haven’t properly looked into which areas they should let people into, and which they should not.

So for Nanjiluo, we need to do two things – revise the overall [existing] plan, and make a proper plan to manage the area.

We don’t really have management plans for protected areas in China right now. These should include tourist management, administrative management and operations management, such as which months the scenic spot is open for tourism and how many tickets can they issue. We need to do proper research on that [to establish maximum capacity and ensure the environment is not impacted].

Authorities in Nanjiluo should not simply close it and ban entry. They might need to build a fixed route for tourists with a paved or gravel road, or a boardwalk. If tourists stray off the path and trample on the grass, they could be fined.

We need to draft a plan to regulate this wild scenic spot of Nanjiluo. One recommended concept is to adopt the LAC model of responsible tourism. This refers to “Limits of Acceptable Change,” which means limiting the number of human activities in protected areas, reducing the intensity of the impact of human activities on the ecosystem, and controlling human activities within an acceptable “red line” to ensure the ecosystem’s stability. In other words, humans can bring changes to the environment, but not irreversible changes. Tourism activities should minimize the impact of human actions on the ecological environment.

Old Version

Old Version