Thirty-five years later, Sanxingdui stunned the world again in 2021 after the discovery of six more sacrificial pits with over 13,000 numbered artifacts unearthed. In 2023, the new Sanxingdui Museum opened with great fanfare, displaying many of these artifacts for the first time. Yet even this could not fully satisfy the intense curiosity surrounding the mysterious Sanxingdui culture.

There have been countless reports and speculation in films, images and articles about the Sanxingdui finds, especially the bronze ware items. One in particular, the “Bronze Sun Wheel,” stands out as an artifact that is both representative and fascinating.

The Bronze Sun Wheel, measuring 88 centimeters in diameter, is a perfectly symmetrical five-spoke round disk, so well-crafted that it could easily be mistaken for a steering wheel on a bus. This likeness makes the artifact particularly popular with children, who often let their imaginations run wild as to its use. Their takes are as good as anyone’s, as even archaeologists do not know its exact purpose.

Among the more entertaining suggestions is that a contemporary time traveler accidentally left the steering wheel at Sanxingdui. Or maybe it is a steering wheel from an alien spacecraft that visited Earth 3,000 years ago.

A more realistic theory is that it might have been a part of some wheeled device, such as a cart, a spinning wheel or a waterwheel, all of which could have existed during that era.

However, archaeological findings do not support this. First, no mechanical parts have been found among the tens of thousands of artifacts at Sanxingdui. Second, practical tools typically started with wooden or stone versions before more valuable bronze ones were made, but no such tools have been found at Sanxingdui. Third, even if it were a part of some practical device, early technological methods would make an even number of spokes for symmetry much simpler to craft. Creating an even five-spoke design would be difficult even for modern artisans working by hand.

In August 2024, during the opening ceremony of the Paris Olympics, the Olympic flame was hoisted aloft over the Tuileries garden next to the Louvre by hot air balloon. The flame was held on a metal disc suspended beneath the balloon. Visitors who had previously seen the Sanxingdui exhibition exclaimed “Could this ‘steering wheel’ also have been used by ancient people to carry a sacred flame into the air for worship and viewing?”

This idea could be closer to the truth. Most ancient bronzes discovered in China were ritual objects, while practical tools, especially agricultural implements, are relatively rare. There are weapons, but these were mainly status symbols for high-ranking nobles and seldom used in battle. Given the scarcity of bronze at the time, it was reserved for the most important ritual uses.

Ritual objects, or liqi in Chinese, were used in ceremonial contexts, such as formal ceremonies, entertainment and ancestor worship, as well as to ward off evil. People believed these objects deserved to be made from the most precious materials with the finest craftsmanship. Bronze was among the most esteemed material for creating these ritual objects, highly favored by the ruling class and nobility.���

This “steering wheel” is considered representative among Sanxingdui artifacts because like the bronze standing figure, masks and sacred tree, it has all the tell-tale signs of a ritual object: expensive materials, exquisite craftsmanship and unique design. However, since no written records have been found at Sanxingdui, the exact purpose of these bronze ritual objects remains a mystery, making it one of the many unsolved mysteries of Sanxingdui culture. Parsing their religious belief system could help answer other questions as to Sanxingdui’s cultural origins and influences, whether from Central China, ancient Mesopotamia or ancient India.

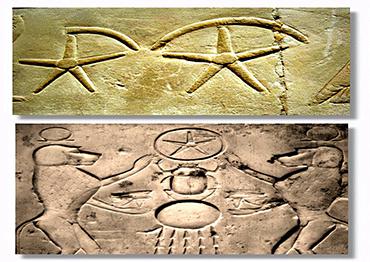

This bronze artifact might hold the key to unlocking these mysteries. If it was a practical object, like a wheel, then considering the oldest wheels were created by the ancient Mesopotamian civilization of the Tigris and Euphrates, roughly in today’s Iraq, it would suggest that Sanxingdui culture was significantly influenced by ancient Western Asia. However, if it is a ritual object, what was its purpose? A common theory among experts links its design to primitive sun worship, which inspired the name “Bronze Sun Wheel.”

Old Version

Old Version