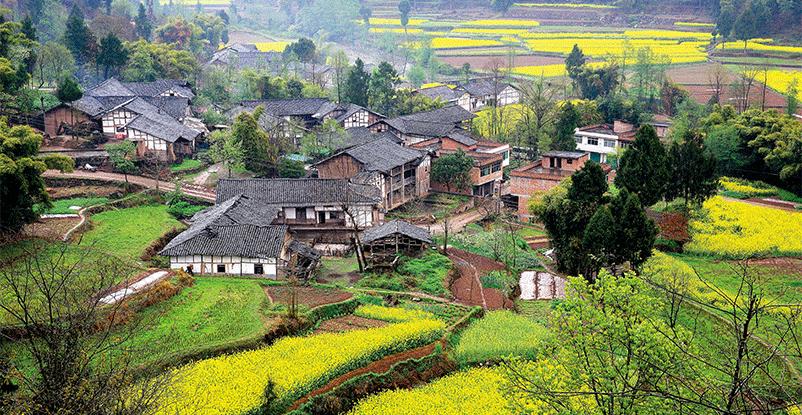

It is somewhat of a miracle that the village and the clan have survived, particularly as urbanization is so rapid now. Enhanced initiatives in traditional village preservation and the rural revitalization program have seen an extraordinary push to preserve traditional villages.

Factors including neglect, population increases, destructive political rampages and rural-urban migration have resulted in the loss of many villages of historic importance.

Many cultural experts started calling for government assistance to preserve ancient villages several decades ago. The first national strategy came in 2003, when the Ministry of Construction and the State Administration of Cultural Heritage organized the initial selection of “Famous Towns and Villages in Chinese History and Culture.”

But due to the lack of real government-supported efforts, many traditional villages were lost anyway. Statistics from the Ministry of Civil Affairs indicate that from 2002 to 2012, the number of villages nationwide dropped from 3.6 million to 2.7 million. According to the Research Center for Chinese Village Culture at Central South University, the total number of ancient villages with historical, ethnic, regional cultural and architectural value was 9,707 in 2004, but only 5,709 remained in 2010. In 2014, the Chinese Traditional Village Culture Research Center returned to 1,033 traditional villages in the Yangtze River and Yellow River they had surveyed in 2010, and found that 461 villages had disappeared.

Shao Yong, a professor at the School of Architecture and Urban Planning at Tongji University has been researching villages since the 1990s. She told NewsChina that many of the disappeared villages and towns could be considered traditional relics with certain inherent characteristics, but they still have relatively little historical and cultural value based on evaluation criteria for both visible and intangible heritage. Thus not all can be listed as “significant,” so they will not be protected.

In April 2006, two of the foremost experts in cultural preservation in China, author and scholar Feng Jicai, director of the China Traditional Village Protection Expert Committee at Tianjin University, and Ruan Yisan, a former professor of urban planning at Tongji University, convened the International Forum on the Protection of Ancient Villages in Xitang, Zhejiang Province. It attracted researchers from all over the world to discuss the value, significance, methods and approaches to preserving ancient villages. At the closing ceremony, all participants agreed on the “Xitang Declaration” which said: “We call for an immediate investigation and survey of Chinese ancient villages and their cultures, to find out the basic situation of our cultural heritage, establish a complete list of ancient villages, and carry out classified protection.”

This forum resulted in several nongovernmental initiatives led by scholars and universities that aimed to investigate the situation of ancient villages and provide guidelines for research and protection efforts. In 2007, Tongji Urban Planning and Design Institute and China Land Economics Association launched the selection process for “China Landscape Villages,” and in 2010, Chinese Folk Literature and Art Association and the School of Architecture of Tsinghua University selected representative ancient villages.

Although they wanted to attract attention to the cause of preserving ancient villages, since their efforts were not government backed, there was little actual effect.

In 2011, there was a turning point. In June 2011, at the symposium on the 60th anniversary of the China Central Institute for Culture and History, Feng gave a speech on the lack of preservation of ancient villages. In September, he submitted suggestions on the preservation of ancient villages to the government. Finally, in April 2012, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, the Ministry of Culture, the State Administration of Cultural Heritage and the Ministry of Finance issued a “Notification on the Investigation of Traditional Villages,” which for the first time, would protect traditional villages at the national level.

In September 2012, the government set up an expert committee to evaluate and identify ancient villages, and choose which to put on an official list recognizing them as such. The first list of 646 traditional villages was announced on December 19 of that year, and another 915 villages were added to the protection register in August 2013.

Funds and publicity soon followed. At the beginning of 2014, China’s No. 1 central document (which focuses on rural policymaking) proposed to “formulate plans for the protection and development of traditional villages, promptly select traditional villages and dwellings with historical and cultural value onto the protection list, and increase investment and protection efforts.” In March 2014, the Ministry of Finance announced funding of 11.4 billion yuan (US$1.57b) in the following three years to promote village preservation.

By September 2014, enthusiasm was so great that 4,548 villages applied to be listed, with 994 chosen. Driven by the momentum of national efforts, local governments launched their own assessments. A fervor for traditional village preservation swept across the nation, at government, academic and business levels.

Some universities set up research institutes. In 2013, Tianjin University established the Research Center for the Protection and Development of Chinese Traditional Villages, providing standards and suggestions, communication concepts and methods to protect villages.

In 2014, Central South University also set up the Chinese Village Culture Research Center, dedicated to creating an interdisciplinary platform incorporating historical anthropology, cultural anthropology, ethnic linguistics, architecture and materials.

Many enterprises set up non-profit funds to help traditional villages financially. In November 2014, an NGO named Friends of the Ancient Village was established. It raised funds, set up volunteer networks and monitored the destruction of villages through a hotline service. Its founder, Tang Min, told NewsChina that he has visited over 2,000 listed traditional villages, and he remains absolutely impressed by “the best traditional Chinese culture embedded in that heritage.”

Old Version

Old Version