From the Han Dynasty to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the Classic of Mountains and Seas was seen as a geographical work. During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), however, the book was reclassified as a novel, because of its bizarre and fantastical content and inaccurate records of geographical directions. Today, most Chinese regard the Classic of Mountains and Seas as mythology. For Western readers accustomed to Greek mythology and Norse sagas, the style in which the Classic of Mountains and Seas is written might come as a shock. It resembles neither the Homeric epic nor Eddic poetry and prose. Instead, it is an encyclopedic mythology that combines a geographic compendium, a species guide and a witchcraft manual.

Chen Lianshan, professor of folklore and mythology at Peking University, interprets the Classic of Mountains and Seas as a government-compiled and somewhat primitive geographical treatise. According to Chen, the significant discrepancies between the records in the book and the reality today are easily explained by the great changes that took place over time. Mountains may remain steadfast, but waterways and natural surroundings are highly variable.

Perhaps the most fascinating part of the book is its treasure trove of mythology. The Classic of Mountains and Seas stands out as the most significant mythological text from ancient China. As Lu Xun, father of modern Chinese literature, noted, “China’s myths and legends have yet to be compiled into a dedicated book, remaining scattered throughout ancient texts, with a significant concentration found in the Classic of Mountains and Seas.”

The mythological gods, deities, spirits and creatures described in the book are referenced in many places throughout Chinese folklore. Three of the most well-known stories are “Nüwa Patching the Sky,” “Jingwei Filling the Sea” and “Kuafu Chasing the Sun.”

The first story is about the mother of the Chinese nation, Nüwa. Legend has it that after Nüwa created humans, they lived peacefully and happily for a long time. One year, the water god Gonggong and fire god Zhurong started fighting. In the end, the fire god emerged victorious. Feeling angry and ashamed, the water god smashed his head against Mount Buzhou Mountain, a giant pillar supporting the sky. The mountain collapsed, which allowed a corner of the sky to fall. On the ground, enormous cracks opened, forests erupted in flames, floodwaters spurted from the ground and ferocious creatures wrought havoc.

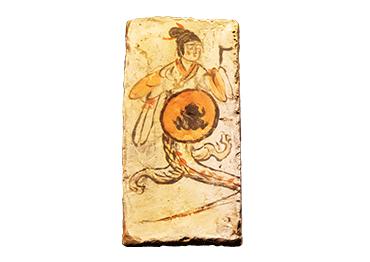

Nüwa felt terribly distressed and decided to patch up the sky to put an end to the human suffering. She collected multi-colored stones, set a great fire to smelt them into a slurry, and used the slurry to plaster up the hole. Then she chopped the feet off a giant turtle and used them as four pillars to support the sky. After Nüwa’s toil, the sky was mended, the ground was even, the waters stopped and the people once again lived in peace and happiness.

The second story “Jingwei Filling the Sea” tells of the youngest daughter of the Yan Emperor, who was a legendary tribal leader in ancient China and revered as one of the founding ancestors of the Chinese people. One day the girl went swimming in the Eastern Sea and drowned. After her death, her soul transformed into a divine bird called Jingwei, which resembled a raven, with a patterned head, white beak and red feet. Enraged with the sea that had taken her life, Jingwei began to carry branches and stones from the Western Mountain, day in and day out, to fill up the Eastern Sea.

Today, Jingwei filling the sea is not just an ancient story, but has also become an idiom describing a futile and never-ending task. Jingwei can be seen as the Chinese equivalent of Sisyphus from Greek mythology, who was cursed by Zeus to roll an enchanted boulder uphill forever. From another perspective, both Jingwei and Sisyphus represent a positive meaning – dogged determination in the face of overwhelming odds.

“Kuafu Chasing the Sun” is also associated with the Yan Emperor. Kuafu, a descendant of the Yan Emperor, was a giant with immense strength. In his time, the sun scorched the earth, making life unbearable. Kuafu decided to chase the sun and stop it from causing so much suffering. He set out westwards, running with incredible speed to catch the sun. As he ran, he drank from rivers and lakes to quench his thirst, but the heat from the sun was so intense that he could not find enough water. Eventually, he collapsed from exhaustion and dehydration. As he fell, he transformed into a mountain, and his wooden staff turned into a forest of peach trees. The forest provided shelter for travelers, and the peaches quenched their thirst.

Kuafu is often interpreted as a symbol of human determination and the pursuit of the impossible. Despite his failure, Kuafu’s spirit of perseverance and his willingness to sacrifice himself for the greater good are still celebrated in Chinese culture. The story of Kuafu has not only inspired writers and artists, but in 2022 the name Kuafu was chosen for China’s first satellite designed to carry out comprehensive probes of the sun.

Old Version

Old Version