The Jebum-gang Art Center is the first public cultural space in Xizang created through the adaptive reuse of a historic building.

Built in the latter half of the 19th century, Jebum-gang means “Holy Place of 100,000 Tsongkhapas” in Tibetan. This is because the site once featured a five-story stupa that housed 100,000 tsatsas, or small molded clay sculptures of Tsongkhapa (1357-1419), founder of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism.

The structure follows a central theme in traditional Tibetan architecture – the mandala. Originally meaning “palace of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas,” the mandala represents the ideal, complete and resplendent world in Buddhist cosmology.

The construction of Jebum-gang embodies this ambition. According to historical records and photos, the lower level of Jebum-gang Temple featured a large main hall equal in length on all sides. Embedded within its walls were the 100,000 tsatsas salvaged from an earlier stupa on the same site that had collapsed.

Above the main hall stood nine additional shrines. The central shrine, slightly larger, housed three Buddha statues. At each of the four corners were tower-like shrines dedicated to the Four Heavenly Kings, believed to watch over each cardinal direction. Between these towers were four smaller chapels, completing the symmetrical layout.

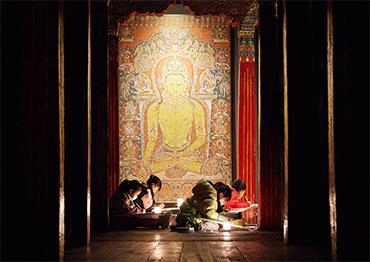

A feature of Jebum-gang Temple is its interior murals. They convey traditional Tibetan understandings of sacred space in textbook-like detail. With dynamic compositions and refined brushwork, these murals are considered outstanding examples of late 19th century Tibetan painting.

Delving into the historical context of the temple’s construction reveals that these systematically arranged murals also held a deep functional significance during wartime.

The space was constructed during a time of foreign influence in the region, when Britain and Russia were locked in a strategic rivalry over control of Xizang.

“In response to this looming threat, the local government, then under the control of the Gelug school, collaborated with monks from the Nyingma school. They incorporated an entire set of special ritual sequences into the murals, aiming to construct a spiritual defense mechanism through religious means,” said Fang Kun, who is also director of the China Association for Preservation and Development of Tibetan Culture.

Yet these efforts could not prevent the British invasion of Lhasa in 1904. In an old photograph, British troops are seen swaggering past Jebum-gang, surrounded by helpless Tibetan monks and civilians.

In the aftermath, the building underwent numerous transformations, serving at various times as Xizang’s first electrical substation, a grain bureau warehouse and residential housing. The once-pristine architectural features and exquisite murals endured long years of neglect and deterioration.

Since the late 20th century, scholars from both East and West have begun to recognize the academic value of the structure. Himalayan architectural preservationist Andre Alexander and his team paid particular attention to Jebum-gang Temple during their research on Lhasa’s old city. In his book The Temples of Lhasa, he described it as “one of the most inspiring examples of (recent) historic Tibetan architecture” and “highly deserving of protection.”

It was not until 2017 that Lhasa’s municipal and Chengguan District governments took the lead in funding Jebum-gang’s protection and restoration, inviting a team of professionals specializing in historical architecture conservation. However, fully revitalizing the temple and realizing its contemporary cultural value remained a formidable challenge.

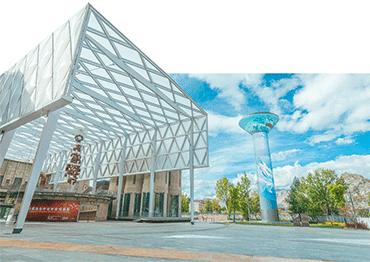

In 2018, local authorities commissioned cultural enterprise Tihho to transform the space into an art center. Through a series of upgrades, including waterproofing, electrical, museum-grade lighting and the creation of functional spaces, the team breathed new life into the building, making it suitable for hosting international exhibitions and cultural events.

“In promoting Tibetan culture abroad, we realized that many in the Western world still hold outdated stereotypes and Orientalist fantasies about Xizang,” said Fang Kun, who has worked in Tibetan contemporary art promotion for over a decade. “Some people still imagine Tibetans living primitive lives or believe Xizang is some ethereal, untouched Eastern utopia. There are even those in the West who think Xizang should remain frozen in time and oppose its modernization. But Tibetans not only have a rich traditional culture, they also have a thriving contemporary culture. Unfortunately, this side of Xizang is often overlooked.”

In July 2021, Jebum-gang Temple was reborn as the Jebum-gang Art Center, opening to the public with free admission. Since then, it has hosted a series of contemporary exhibitions and cultural programs such as The Living Old City, Traditional Tibetan Tiger Rugs and the Infinite Cosmos digital art show, blending Tibetan elements with modern artistic expression. The center has become a venue for cultural education programs for primary and secondary school students, as well as public performances of intangible cultural heritage.

Old Version

Old Version