enowned filmmaker Lu Chuan has always had a deep passion for wildlife conservation.

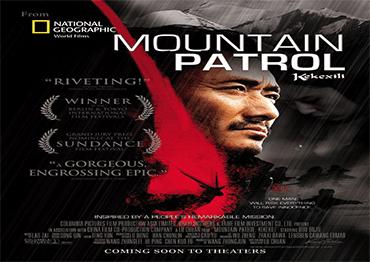

In 2004, Lu’s highly acclaimed film Mountain Patrol: Kekexili told the true story of volunteers who banded together in the 1990s to protect the once-endangered Tibetan antelope from poachers in Kekexili (Hoh Xil) National Nature Reserve, a mountainous wilderness in Qinghai Province. The gritty and uncompromising film revealed the bleak reality faced by the species, whose population had plummeted to as low as 50,000 in the mid-1990s, mainly due to rampant poaching. After years of conservation efforts, the population has rebounded to more than 300,000 in 2024, according to statistics from Xizang’s Department of Ecology and Environment.

In 2016, Lu directed the documentary Born in China for Disneynature and Shanghai Media Group. Filmed over the course of a year, it captures intimate moments in the lives of five rare animal species: snow leopards, pandas, golden monkeys, red-crowned cranes and Tibetan antelopes.

On May 20, 2025, the 54-year-old director presented his latest documentary on wildlife conservation on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau at the 78th Cannes Film Festival. The 30-minute film highlights China’s innovative approaches to wildlife rescue and conservation at the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau Wildlife Park (QWP) in Xining, Qinghai Province. The zoo is known for its “QWP Model,” which incorporates AI technology to care for injured animals, assess their survival prospects and prioritize their reintroduction into natural habitats.

During the screening at Cannes, Lu spoke with China News Service about the making of this documentary on wildlife conservation on the QinghaiXizang Plateau and his two-decade journey creating wildlife-themed films.

CNS: What message do you want to convey through this new documentary on wildlife conservation on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau?

Lu Chuan: Over the past 20 years, I’ve made three films related to wildlife conservation. The first was Kekexili: Mountain Patrol, which was filmed in Kekexili (Hoh Xil) in 2002 and released in 2004. The second was Born in China, a film made in collaboration with Disney in 2013. And 10 years later, I made this documentary on wildlife conservation on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau. It’s hard to describe what it feels like to spend 20 years documenting a country’s and a region’s wildlife conservation efforts, with the profound changes that have taken place in the country, among conservation researchers and volunteers, among protected animals and reserves, and in the overall commitment and perseverance behind wildlife protection. When you watch these three films, you’ll see that there’s not the slightest exaggeration or embellishment. They are faithful records.

From the harsh environment of Kekexili to Born in China and now to this documentary on wildlife conservation on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau, these three films show continuous and positive changes in both the landscapes and the animals living in those reserves.

Twenty years ago, the Wild Yak Brigade in Kekexili (Hoh Xil), along with their sponsor the Western Committee founded by Sonam Dargye who was a local county official, had a very simple idea. They just wanted to keep the animals alive. Today, a new generation of wildlife conservationists has a broader vision. They focus on animal care, rewilding and providing medical treatment. These ideas have evolved alongside China’s own development and progress.

My new documentary on wildlife conservation on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau is the result of many people’s ideas and efforts. It shows the process of rescuing and protecting a large number of wild animals. I hope the film, as part of the international exposure made possible by the Cannes Film Festival, can faithfully present the development and philosophy behind China’s conservation work.

In my view, all individuals and organizations involved in wildlife conservation are part of one big family, united by the same ideal. We’re not trying to promote anything. The greatest value of a documentary is its honest record of the times.

CNS: What challenges did you encounter when filming this documentary on wildlife conservation on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau? How has your mindset changed over the 20-years you have been directing films about humans and nature?

LC: This time, the experience felt very different from when we filmed Kekexili. Back then, as soon as we arrived, we were told what not to do to avoid altitude sickness: no running, no heavy exercise, no bathing, no drinking. But we challenged every one of those rules. I took bare-chested photos with mountain patrollers at the Kunlun Mountain Pass and played basketball with local young lama monks on a court next to the temple. At that time, I was fanatical, driven by simple faith and some foolhardiness.

As we filmed Kekexili, we lost a lot of people on our crew. We started with 108 people, but that shrank to around 40 or 50. More than half fell ill, and some had to be hospitalized for emergency treatment. I think I was the only one who didn’t have any major issues. But after returning from the plateau, I began to lose my hair, maybe from the exhaustion I pushed through up there.

When we filmed Born in China in 2013, I wasn’t as daring as before. Arriving in the Sanjiangyuan area where the Yangtze, Yellow and Lancang (Mekong) rivers originate, I quickly felt out of breath, especially in Kekexili. By the second or third day, I’d get nosebleeds and had to go down to Golmud [Qinghai Province], where the altitude is lower, to recover a bit, or even return to Xining [capital of Qinghai], which sits at about 3,100 meters.

This time, when filming this documentary on wildlife conservation on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau, I had more severe altitude sickness. After flying to Xining, I had a splitting headache that night and couldn’t sleep. The next day, I had to rely on an oxygen bottle, even though Xining isn’t even that high.

China’s wildlife conservation has made great leaps over the past 20 years, and I’ve been fortunate to document those changes across three films. It has been a moving experience. These groundbreaking changes are possible because of China’s growing prosperity and strength, and because of increased public awareness of conservation. The first generation of conservationists faced incredibly harsh conditions and real danger. Sonam Dargye and Dhakpa Dorjee, local officials and leaders of the Wild Yak Brigade, even sacrificed their lives. [Sonam Dargye was killed by poachers while attempting to report them to police in 1994. Four years later, Dhakpa Dorjee was found shot dead in his home. Local authorities later ruled it a suicide.]

By the time I started working on Born in China, conservation efforts were in much better shape. Conditions had improved significantly, and there was more funding support.

Today, wildlife parks are no longer places where animals are simply imprisoned for life. At Xining Wildlife Park, conservationists use cutting-edge equipment for data collection, cloud storage and real-time statistics. They have a very advanced philosophy in terms of rescuing, treating and rewilding animals.

I used to see zoos as cruel places, but after visiting Xining Wildlife Park, I saw what a zoo could be like, especially in that a wildlife zoo can become a kind of nursing home for injured or disabled animals, a place for elder care or hospice. At the same time, it can help animals recover, breed and eventually re-adapt to the wild before being released. You can really feel that China’s approach to wildlife conservation has become very advanced, not only in terms of technology, but also in its ethical and moral outlook.

CNS: Where do China’s wildlife conservation-themed films stand compared with their peers in the rest of the world?

LC: Frankly speaking, the development of China’s wildlife documentary industry does not match the progress of its conservation work. The conservation efforts have achieved far more than what has been captured in films or video records.

There should be more domestic productions dedicated to documenting animal conservation in China. For example, films could show the living conditions of the country’s rarest wild animals in 2025 and the work being done by China’s conservationists, so more children and families can see and learn from them.

No matter how much we do to protect or intervene, each year we still witness the extinction of certain species. What we can do, it seems, is slow that process. We should document these animals to preserve their final beautiful images while they still exist and to draw more public attention to their plight.

CNS: AI has brought many changes to the movie industry and is also used in this new documentary. How do you view AI’s impact on filmmaking?

LC: From an ethical perspective, the use of AI in animal conservation documentaries should be limited, because they require authenticity. In this documentary on wildlife conservation on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau, AI was not used for image generation but rather for processing wildlife-related big data, running simulations, and helping with data analysis. This helped scientists make earlier predictions about disease prevention and treatment in wild animals, and not image creation.

I think AI is triggering profound changes to the entire industry and production process. It can quickly realize your ideas. It speeds up production and visualization. Plus, it lowers the barriers to film production. AI will transform the entire film industry’s ecosystem.

Old Version

Old Version