Sidelined for nearly a century in literary circles, Chinese science fiction has finally entered its golden age – and shot into the global spotlight

After watching the smash sci-fi hit The Wandering Earth over the Spring Festival in February, sci-fi writer Fei Dao’s friends were convinced that he would make a fortune in the near future. Fei Dao (penname of Jia Liyuan), who China’s leading sci-fi writer Liu Cixin once described as “a brilliant sci-fi poet,” has published three collections of short stories, including The Storytelling Robot. However, for years, no matter how much acclaim he gathered in China’s small sci-fi community, his profession was still alien to his friends.

That’s why the 36-year-old was quite surprised by their sudden change in attitude. “One of them said to me, ‘[Liu Cixin] stands to earn a whole lot from the film. You are now in the eye of the storm, man. You can write one yourself and make it a movie next time!’” Fei Dao told NewsChina.

Released on February 5, The Wandering Earth is China’s first sci-fi blockbuster and second highest-grossing film in the country’s cinematic history, raking in over $700 million worldwide. From the global fever of Liu Cixin’s sci-fi works to the box office miracle of The Wandering Earth, more people home and abroad are recognizing the rising power of Chinese science fiction. Having been a niche market for about a century, science fiction is now one of the most popular genres of literature in China. It’s even been dubbed China’s greatest cultural export since kung fu.

We Have Liftoff

It is impossible to speak of Chinese science fiction without talking about Liu Cixin. His masterpiece, the Three-Body trilogy, comprising The Three-Body Problem, The Dark Forest, and Death’s End, almost single-handedly launched Chinese science fiction into a golden age.

The red-letter day came in 2015 when Liu’s The Three Body Problem became the first non-English work to win a Hugo Award. Before that, China’s science fiction had zero commercial potential. Nearly no one in China was writing sci-fi full time.

In 2016, Hao Jingfang became the second Chinese writer to win the Hugo Award with her novella Folding Beijing, further garnering international attention for the genre.

Since 2015, Chinese science fiction stories have been making their way into the Anglosphere – many translated by the Chinese American sci-fi novelist and translator Ken Liu. The Hugo-winning magazine Clarksworld started a Chinese science translation project in 2015 and has been publishing one Chinese sci-fi short story a month.

China’s sci-fi industry recorded an output value of over 14 billion yuan (US$2b) in 2017 and nearly 10 billion yuan (US$1.45b) in the first half of 2018, according to an industry report by the Southern University of Science and Technology.

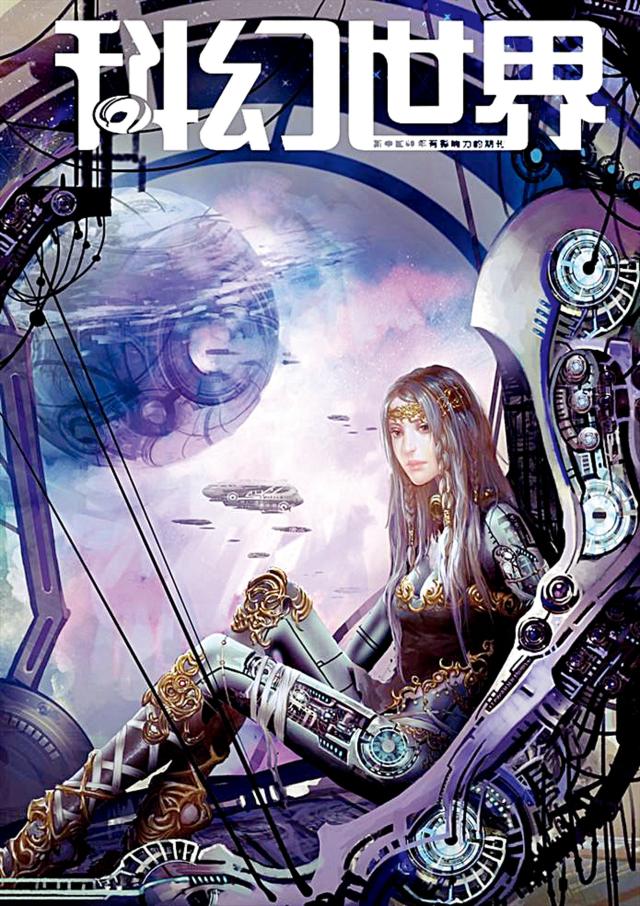

Sci-fi fans describe Liu, together with Han Song, Wang Jingkang and Hexi, as “The Big Four” – authors that laid the foundation for contemporary Chinese science fiction. There is a generation of younger writers born after 1980 that have also risen to fame in the latest sci-fi boom, such as Chen Qiufan, Bao Shu, A Que, Zhang Ran, Ma Boyong, Jia Liyuan and Chang Jia. Female writers occupy a conspicuous spot in the scene. Besides Hao Jingfang, other talents include Xia Jia, Chi Hui, Gu Shi, Wang Yao and Zhao Haihong.

“Today Chinese science fiction is no longer obscure and isolated, and the genre’s journey to the West is no longer hesitant,” said modern Chinese literature expert Song Mingwang, “It has become a fresh new force that is helping shape the outlook of global science fiction.”

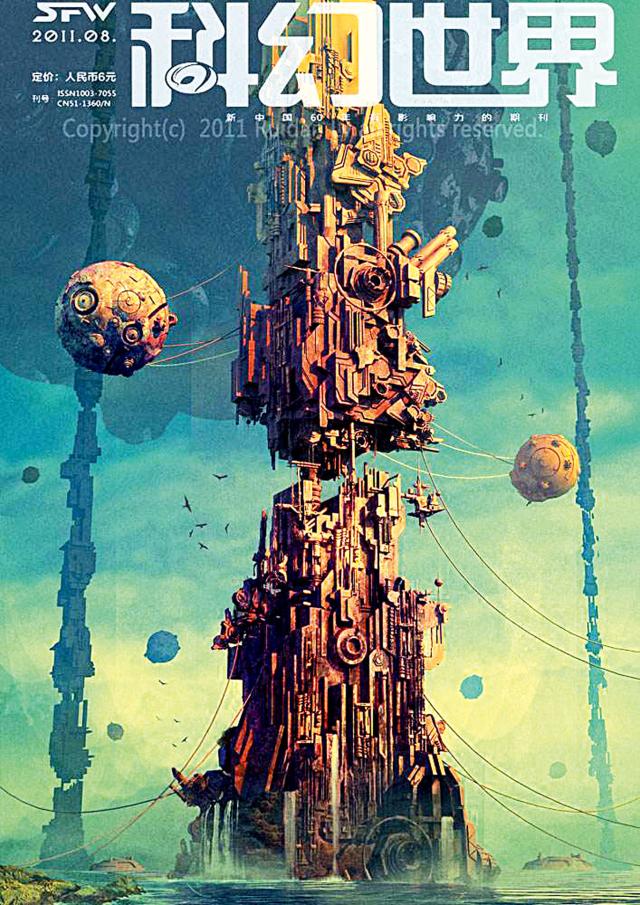

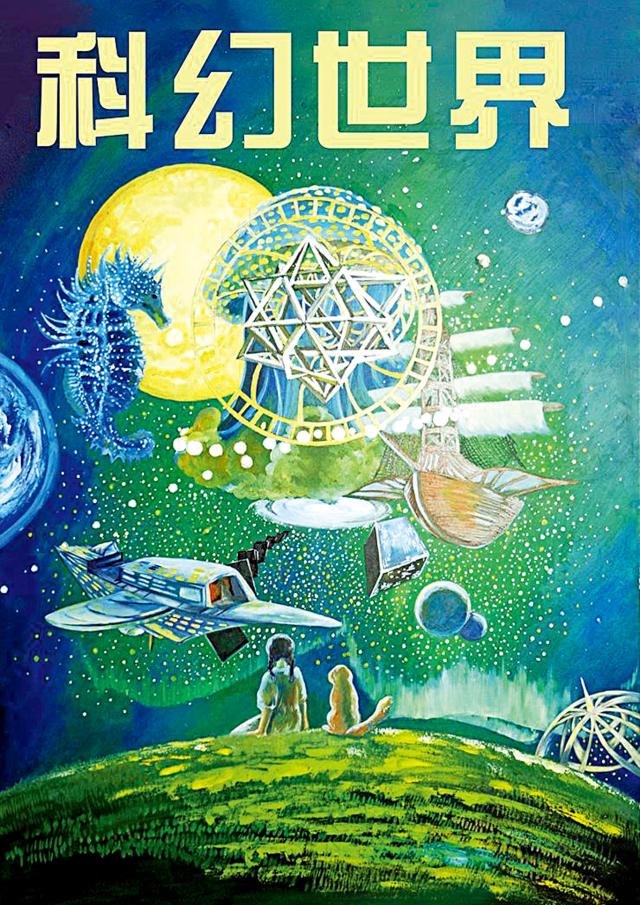

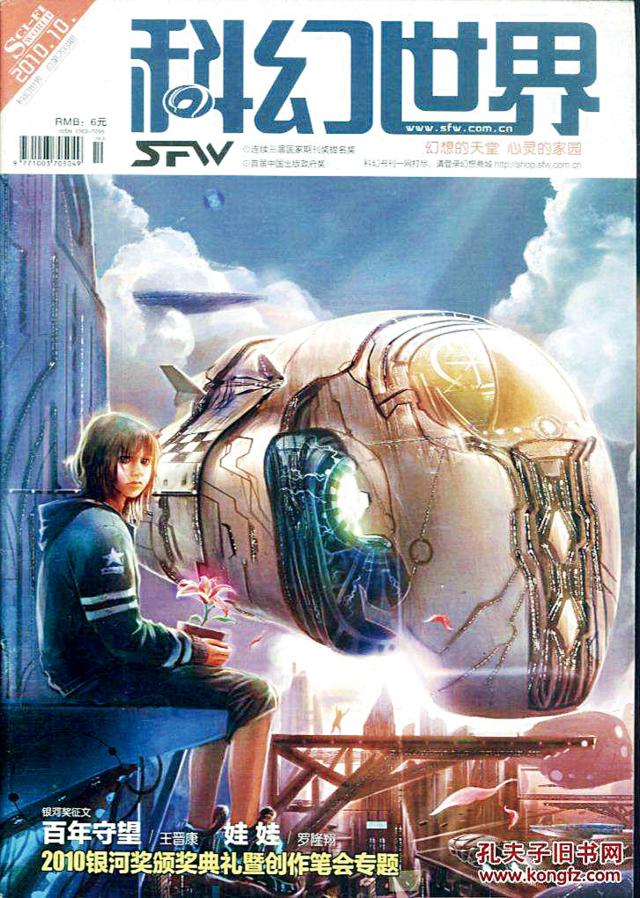

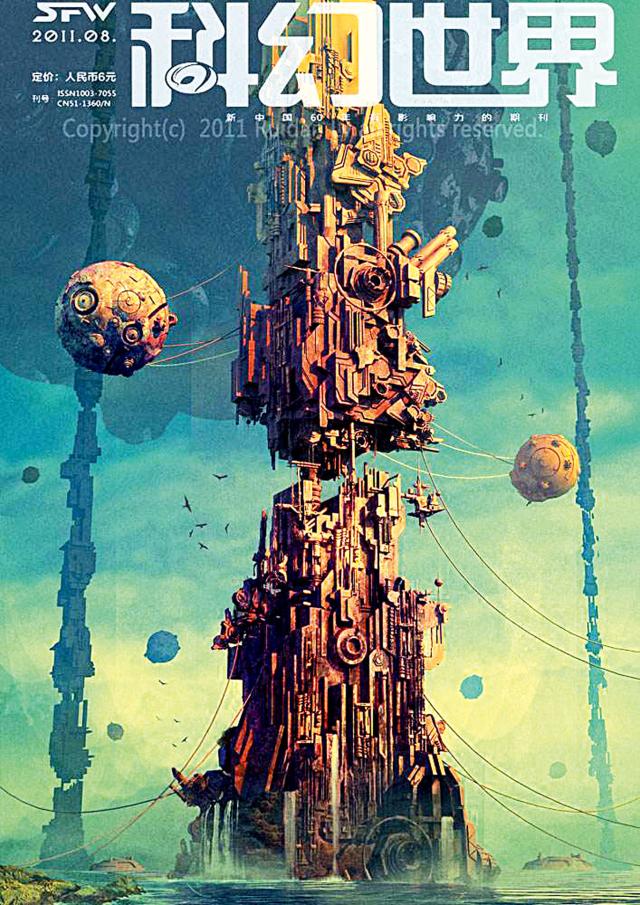

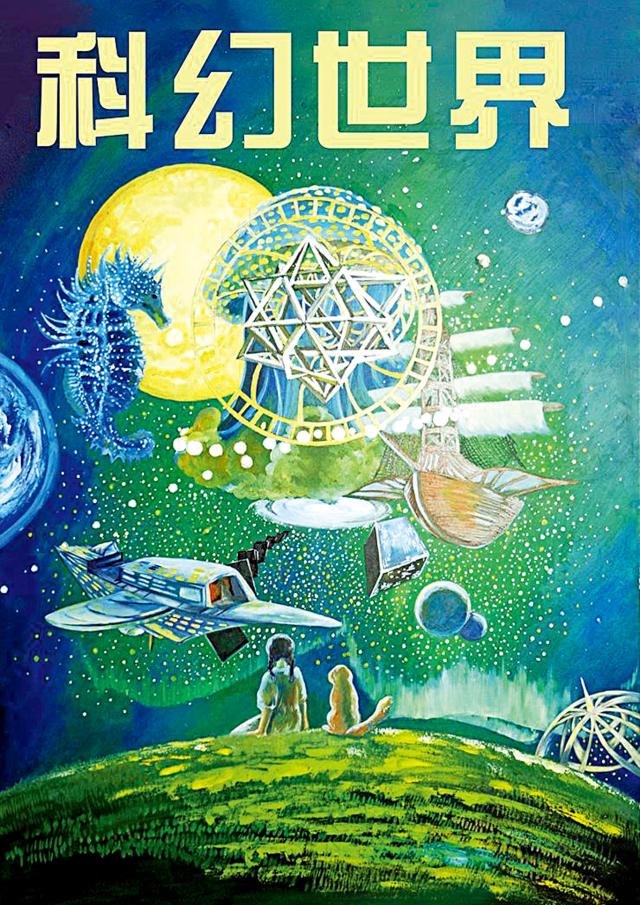

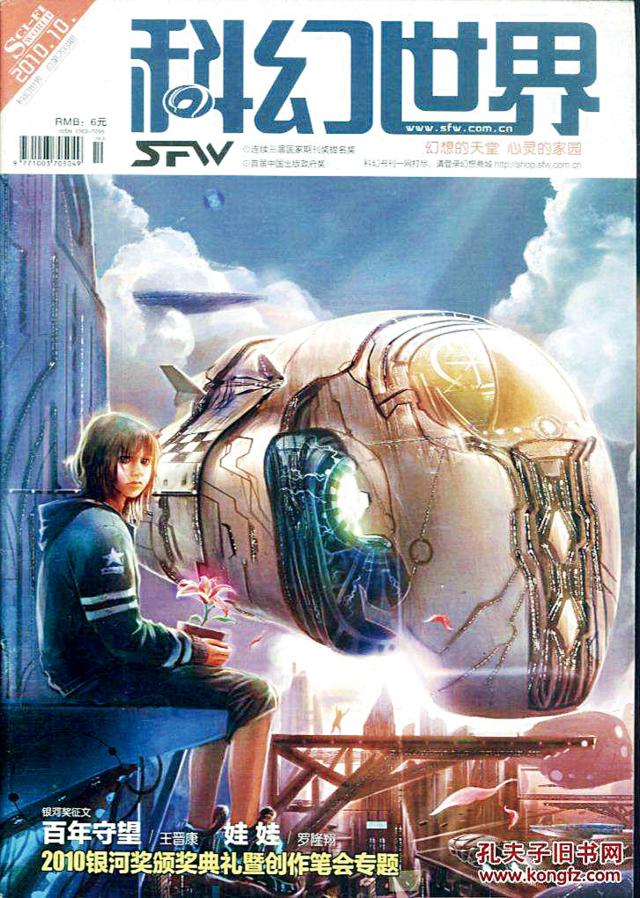

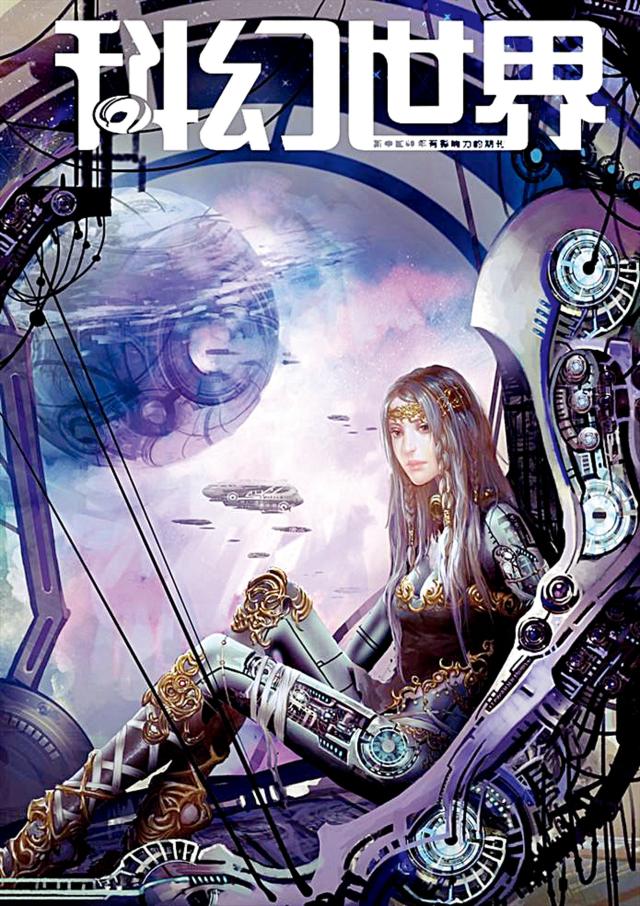

“The success of the Three Body trilogy and The Wandering Earth have turned the public’s attention to Chinese sci-fi and also encouraged sci-fi writers to invest more energy in creating quality content,” Qian Lifang, an author known for her historical science fiction, told our reporter. Qian said she’s overjoyed to see sci-fi’s popularity blast off in China, something she never thought would happen. Born in 1978, Qian grew up reading Science Fiction World, China’s biggest sci-fi magazine, something she describes as a “lonely habit” because no one she knew took any interest.

“Science fiction for most Chinese readers was rather strange and foreign. Many felt the subject, content and characterization of sci-fi stories were too unfamiliar, as if they were reading translated literature. Most people favored literature with strong elements of Chinese culture, particularly martial arts fiction,” Qian told NewsChina. “I always hoped that I could write sci-fi as engaging and page-turning as martial arts novels.”

A high school history teacher for nearly 20 years, Qian combines her sci-fi writing with ancient Chinese history and culture. Her 2004 debut, The Will of Heaven, is set during the founding of the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) and centers on a confrontation between famed general Han Xin and a powerful alien force disguised as Fuxi, a deity from Chinese mythology who created humankind.

The novel received a Galaxy Award the same year, China’s highest honor for science fiction. Having sold more than 150,000 copies, it was the most popular Chinese sci-fi novel of the pre-Three Body era. Its success also served as inspiration for Liu to write The Three Body Problem. Last year, The Will of Heaven was adapted into 46-episode web series Hero’s Dream.

Bumpy Ride

Literature in China is expected to fulfill a social responsibility. “For a century, science fiction, just as other genres in modern Chinese literature, played a role in transforming traditional culture into modern culture. It had a serious mission to enlighten, spread scientific knowledge and reshape culture,” said author Fei Dao, who is also an associate professor of Chinese at Tsinghua University with a focus on science fiction.

“The vicissitudes of this particular genre have been determined by the country’s struggle to modernize,” he said. The history of Chinese science fiction dates back to the last days of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), when the empire was teetering on the edge of ruin. At the time, a chief concern of Chinese scholars and reformers was how to transform their ancient civilization into a democratic, independent and prosperous modern nation state. China was introduced to Western science fiction through pioneering intellectuals such as the reformist Liang Qichao and the “father of modern literature” Lu Xun as a tool for popularizing science and critical thinking.

Fei Dao described the genre as having “survival anxiety.” In the early 1900s, amid the drive to modernize and clashes with Western powers, Chinese science fiction was full of themes such as “saving the nation from poverty, war and colonial depredations.” In Lu Shi’e’s 1919 Rip Van Winkle-like tale New China, the protagonist wakes up in 1950s Shanghai after a long slumber to experience an advanced, thriving China.

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, science fiction was categorized as a subgenre of children’s literature. Works of this period brim with technological optimism and enthusiasm for progress, development and building a modern nation state.

Chinese science fiction saw a brief resurgence from 1979 to 1983. As China’s reform and opening-up took effect, the influence of Western science fiction became more salient, producing excellent sci-fi magazines and writers. Ye Yonglie was one of the period’s most prestigious writers. His Little Know-all Travels Around the Future World has sold more than 1.5 million copies, and its graphic novel adaptation sold another 1.5 million.

In 1983, an official debate sparked over the nature of sci-fi. Regarding it as a foreign-influenced indulgence, authorities eventually labeled it “spiritual pollution” and suppressed the genre.

“Ye Yonglie wrote a story about a scientist who discovered a dinosaur egg in the Himalayas and incubated it, which authorities criticized as an ‘utter violation of science.’ Another writer was criticized for writing about a marriage between a human and a robot. Such criticisms dealt a hard blow to the small sci-fi community and marred writers’ reputations. Most authors gave up on sci-fi. Nearly all publication of sci-fi magazines and books ground to a halt. Only Science Fiction World struggled to remain,” Wang Jinkang, one of the “Big Four” novelist, told NewsChina.

“Chinese science fiction grew up wild and lonely, not accepted by mainstream literature. We wrote just out of interest. We earned little from our writing and struggled to survive on the fringes of literary society,” Wang said.

But with the mid-1990s came a renaissance. Science fiction, once marginalized in China’s literary landscape, was met with open arms. For decades, Science Fiction World was the only forum for the genre. Today, influential literary periodicals such as People’s Literature, Shanghai Literature, Tianya, Harvest, and Flower City all encourage sci-fi contributions.

“The mainstream fever for science fiction began after Liu Cixin won a Hugo Award. In many cases, the Chinese mainstream does not take something seriously until it’s been internationally acknowledged. It’s sort of a Chinese characteristic,” Chen Qiufan, an upcoming sci-fi writer, told Modern Express.

The Future is Now

Fei Dao feels the new generation of authors born after 1980 have little connection to the last century. When Chinese science fiction diversified, it began to lose its defining characteristics.

“Alien contact, genetic engineering, AI, time travel, space exploration, bizarre diseases and the mysteries of human consciousness – all these subjects have been explored by American writers and have analogues in Chinese science fiction. Chinese writers are attempting to present their thoughts on these issues in a Chinese context,” Fei Dao said.

Attitudes toward science and technology are also drastically different from those in the past. In the essay “The Worst of All Possible Universes and the Best of All Possible Earths: Three Body and Chinese Science Fiction,” Liu Cixin points out, “The optimism toward science that defined much of the last century’s Chinese science fiction has almost vanished. Contemporary science fiction views technological progress with suspicion and anxiety, and the futures portrayed in these works are dark and uncertain.”

Science fiction now serves as a mode of social and political commentary in China. The new generation of sci-fi writers attempts to narrate the social, political and personal conflicts created by modernization and technological advancement. What makes China unique from the rest of the world is the sheer scale and speed of these changes.

Hao Jingfang’s Hugo-winning novella Folding Beijing describes a futuristic mega city divided into three delineated spaces to accommodate the elite, the middle class and the vast poor population. It delivers a strong critique of worsening social stratification, the widening rich-poor gap and other social inequalities.

Chen Qiufan, also known as Stanley Chen, is a leading voice in science fiction realism. His 2009 story “The Year of the Rat” centers on the plight of unemployed university graduates being rallied to hunt Neorats, a species of genetically modified rodents. His debut novel, The Waste Tide (2013) takes place on an island in the South China Sea made from e-waste, a scathing take on excessive consumerism, income disparity and environmental pollution.

Though Chinese science fiction is experiencing a golden age, the entire sci-fi community is still struggling with a major problem: lack of talent.

La Zi, deputy editor of Science Fiction World, points out that for every 10 million people in the US there are 58 sci-fi writers. Japan has 38 per 10 million. In China, that number is 1.5. The US has about 1,500 professional sci-fi writers – China has less than 200, only 50 of whom are consistently producing quality work.

“The best Chinese sci-fi writers have already been internationally acknowledged, but the problem is that such writers are still too few in China. There’s still a huge gap between China and the US in sci-fi writing,” Chen Qiufan told NewsChina.

“We all know that China has Liu Cixin. But almost every year the US might produce a great sci-fi novel as good as Liu Cixin’s works.”

Fei Dao teaches a sci-fi writing course at Tsinghua University to encourage more appreciation for the genre. He is often amazed by his students’ imaginations and advises their revisions. “But when the course is over, under pressure from job hunting or their studies, they neither revise their stories nor talk with me about sci-fi,” he told our reporter.

Qian Lifang is less optimistic than the public about the future of the genre in China. “Chinese sci-fi still has a long way to go,” Qian said. “It’s unrealistic to pursue quality without quantity. Neither monetary incentives nor government support can generate a large quantity of new creators in a short time.”

Old Version

Old Version