Once labeled a capitalist decadence, kissing was banned from Chinese cinema for three decades. But as on-screen kisses sparked controversy, they also started the conversations that are continuing to influence attitudes toward love, sex and relationships

In the summer of 1979, a furious letter landed on the editor’s desk of Popular Cinema magazine. It came from Wen Yingjie, a clerk from a propaganda office in Northwest China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

Wen’s fury was initially provoked by a photo on the back cover of the fifth issue of Popular Cinema: a kissing scene from The Slipper and the Rose, a 1976 British musical film based on the fairy tale Cinderella. The kiss between Cinderella and the prince was pure and beautiful – mild by modern standards. But to Wen, it was utterly wicked.

“How could I believe that such a thing could happen in a socialist nation built by Chairman Mao, a nation which had just been baptized by the Cultural Revolution?” Wen wrote: “It’s such a great pity to see your magazine shamelessly degenerating to a status no different than a capitalist publication. I can’t help but ask – what are you doing?”

“Are kisses and hugs the things most needed in our socialist China?” he wrote. “I’m dead set against any temptation that tempts our people to a corrupted lifestyle – be it hugging, kissing, wearing bell-bottom jeans or cheek-to-cheek dancing. […] Anyone who peddles such a decadent lifestyle should be judged and punished by 900 million Chinese people!”

The angry man further challenged the editors to publish his letter. Popular Cinema did so in its entirety in the eighth issue and started a new column to invite readers to voice their opinions. It sparked an unprecedented debate about kissing that spread across the country. In just two months, more than 11,200 letters flooded into the office and another 3,600 to Wen’s mailbox. “Every day, [the postman] had to carry in two sacks of letters,” one of the editors recalled.

The magazine tallied the letters: less than one-third supported Wen, and the majority expressed their longing to see kisses in publications and in films. The people had spoken – Chinese needed kisses.

Wen was not alone. Behind this mindset was 30 years of normalized sexual repression.

It wasn’t as if Chinese people had never seen an on-screen kiss. There was plenty of kissing in Chinese films from the 1930s. In fact, in the 1936 film Tomboy, audiences watched as a woman kissed another woman while dressed up as a man. One year later, celebrated singer-actress Zhou Xuan and actor Zhao Dan shared a passionate kiss in the 1937 film Angels on the Road. Nevertheless, for nearly three decades after 1949, asceticism had a choke hold on literary and artistic creation. Kissing had been completely banned from Chinese cinema, and any romantic plot lines were barred from the screen. Kissing and hugging were considered degenerate, and even worse, capitalist. Affectionate or sexual displays were taboo and romance was considered a dangerous “bourgeois affectation.”

Zuofeng Wenti (“lifestyle problems”) was a term commonly used from the 1960s and 1980s to describe illicit behavior. Any public display of intimacy with the opposite sex, even holding hands, could spark rumors. An accusation of “lifestyle problems” could be disastrous for one’s life and career.

Titillating Taboos

Chinese people’s views on love and marriage have gone through tremendous changes since reform and opening-up started, particularly after the country’s Second Marriage Law of 1980 was codified.

The 1980 law stipulates that marriage is based on the freedom to choose one’s partner and any coercion by a third party is strictly prohibited. Around the same time, a sentiment had been surfacing in the public consciousness: love was the foundation of marriage.

Films had become a battlefront in the fight against asceticism. But the ice first thawed with a near kiss.

The 1979 feature The Thrill of Life, co-directed by Teng Wenji and Wu Tianming, centers on the struggles of individuals during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76). But what drove audiences to the theater was a kiss – or more accurately, an attempted one.

When the lovers were about to lock lips, the woman’s mother broke in and the couple immediately parted. Though the kiss was unfinished, it was the first time since 1949 that a Chinese mainland film had depicted an attempted kiss.

“As their faces drew closer, the entire theater became uncannily quiet, so quiet that the water running through the theater’s heater could be clearly heard,” screenwriter Jin Zuoren recalled about watching the film 40 years ago. “People held their breath, anxiously waiting for the ‘first kiss on screen.’ All eyes were anxiously glued on their mouths. But alas, at the moment their lips almost found each other, the mother-in-law broke in and put an end to it. The whole theater sighed in great disappointment.”

“This near-kiss announced Chinese cinema’s farewell to that benighted, ascetical age,” Jin added.

The 1980 blockbuster Romance on Lushan Mountain, which sold 100 million tickets across the country that year, set a milestone as the first feature romance made in the Chinese mainland since 1949. China finally had a film that showed people how to love and how to act as a couple.

The love story, set in 1979 as China and the US restored diplomatic relations, focuses on Zhou Yun (Zhang Yu), the daughter of a Kuomintang general who was born and raised in the US, and Geng Hua (Guo Kaimin), the son of a high-ranking Party official. They meet and fall in love during their stays on the picturesque Lushan Mountain in Central China’s Jiangxi Province. Throughout the story, the American-born Zhou Yun plays the lead role in their physical intimacy. Zhou nicknames her boyfriend “Confucius” as the young man has no clue how to show affection. “Oh Confucius! Why can’t you take the lead more?” Zhou Yun teases. She was teaching Geng Hua – as well as audiences – what dating was all about. When Geng Hua is too shy to lean into a kiss, Zhou Yun flirts and says, “You are so silly.” As he braces for Zhou’s kiss, she whispers in encouragement, “You’re so bad.”

The film’s sexual tensions climax with a quick peck on the cheek. And just like that, the taboo of kissing on screen had been broken.

The two actors had never been in a relationship before. Actress Zhang Yu, then 22, was so shy she demanded a cleared set to shoot the scene. Even cordoning off the set for two kilometers did not ease her nerves.

“I was so nervous that I couldn’t find his mouth. I pecked his cheek and just ran away. Guo didn’t know in advance about the kissing scene, so he was so startled by the kiss his face turned red immediately. He was totally petrified, and only came out of it when the whole crew burst out laughing,” Zhang said.

Years later, actor Guo Kaimin revealed they had shot a kiss on the lips that was cut by censors.

Besides the kiss, audiences were also astonished that during the 82-minute film, the lead actress changed her outfit 43 times. Every two minutes she appears with a new, stylish look. Her clothes were purchased in Hong Kong, and many of the outfits would be considered trendy today. At a time when women’s clothes were generally simple, unadorned and unisex, the protagonist’s kaleidoscopic wardrobe dazzled audiences – even her pajamas were embroidered with delicate lace.

Even more shocking for the time, Zhang appears in a swimsuit. Though the one-piece is conservative by today’s standards, the move made it a “nude scene.” People were overwhelmed by the intimate and romantic moments the lovers shared as they played in the creek, cuddled on the bank and gazed into each other’s eyes.

However, the film couldn’t eulogize romantic love without mixing it with love for country. One of the most famous lines from the film is an English expression that the woman taught her boyfriend, “I love my motherland. I love the morning of my motherland.”

The scene is beautiful, but also a little odd. In the summer morning, the lovers chase each other through the woods shouting, “I love my motherland” in English, while “I love you” remains unsaid.

The same year in the film Not For Love, Chinese people saw the first on-screen kiss on the lips – once again, with influence from the West. It tells a love story between Canadian dancer Vera and railway worker Han Yu. At the time, the lead actress, Nicoletta Peyran, was an Italian student studying philosophy at Peking University. To make sure the film survived the censors, their passionate “French kiss” was cut to a three-second “Chinese kiss.”

Hooligan Dancing

As reform and opening-up drove materialism in the country, lifestyles became more Westernized. The burgeoning market economy provided fertile soil for the development of individualism and private rights.

Ballroom dancing was back in a big way. Taiwanese and Hong Kong pop music provided the saccharine soundtrack for the “romantic revolution” that swept China off its feet in the 1980s. Since Romance on Lushan Mountain, attitudes in China had changed tremendously. People’s long suppressed curiosity toward modern lifestyles was finding new outlets.

Hibiscus Town (1986), a film directed by Xie Jin about the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution, broke the record for the longest kissing scene filmed in Chinese cinematic history – four minutes and 23 seconds. Film critics have since praised the kiss as a bold gesture of defiance against sexual repression, comparing it to the classic kiss montage at the end of Italian film Cinema Paradiso (1988).

Sex scenes came in the late 1980s. Acclaimed filmmaker Zhang Yimou’s 1987 directorial debut Red Sorghum has challenged Chinese cinema with a daring and highly stylized sex scene. The protagonist abducts a new bride on her way home after a wedding and the two have sex in a thick sorghum field. Zhang uses the color red to express their animalistic passion, rendering its violence and vitality in red-drenched scenes.

The road to love and sexual freedom was also rough. Values clashed violently amid social transition.

In 1983, authorities launched a three-year nationwide Strike Hard Campaign to curb crime and social unrest. The campaign specifically targeted “hooliganism,” a blanket felony charge that covered everything from gang activity and brawling to public displays of affection. In some cases, hooliganism was tried as a capital crime. That same year, the country launched its three-month Anti-spiritual Pollution Campaign to rein in the spread of Western-liberal ideas and lifestyles.

In the spring of 1983, police charged 15 couples in Shanghai with hooliganism for holding hands, hugging and kissing in a local park.

Public dance parties also were banned. Anyone caught dancing cheek-to-cheek, referred to as “hooligan dancing,” would face prison time.

But this backlash did not last long. In the 1990s, the public developed more open attitudes toward sex. Public displays of affection and revealing clothing were common in big cities. China’s first sex shop opened in 1993. There are now more than 200,000 across the country.

“People are going through a revolutionary change in their mind and behavior,” sexologist and sociologist Li Yinhe told the BBC in 2018. She used the phrase “sexual revolution” to describe these changing attitudes toward love, sex and marriage.

Li conducted two surveys on premarital sex 17 years apart. In 1989, 15.5 percent said they had sex before marriage. In 2016, it was 71 percent.

Lead performers Zhang Yu (front) and Guo Kaimin in Romance on Lushan Mountain, the first romance filmed in the Chinese mainland since 1949

Actors Jiang Wen (left) and Liu Xiaoqing in Hibiscus Town (1986), in which they kissed for four minutes and 23 seconds

The sex scene in the sorghum field in Zhang Yimou’s Red Sorghum (1987)

A bride and groom kiss on a bus

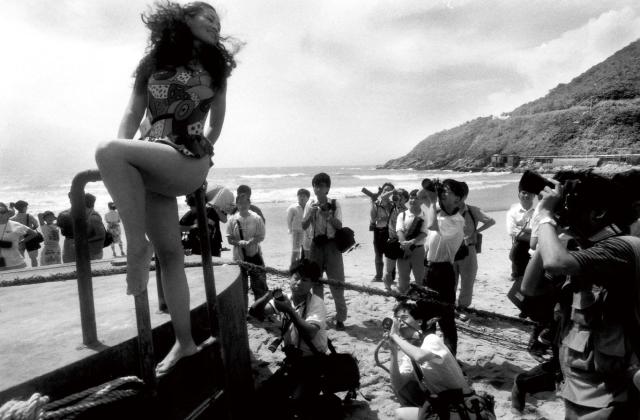

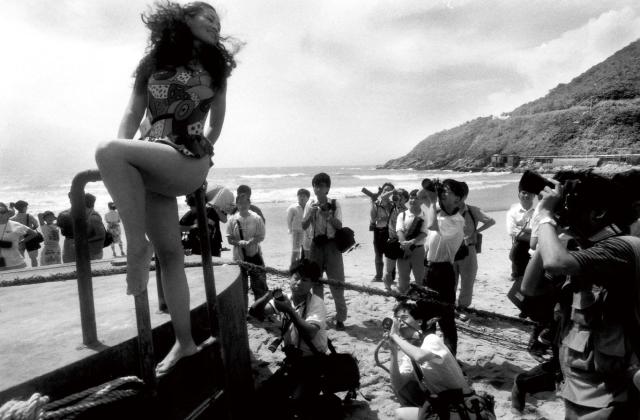

The first swimsuit model photography competition was held in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province in May, 1994, during which a dozen amateur models were invited to pose

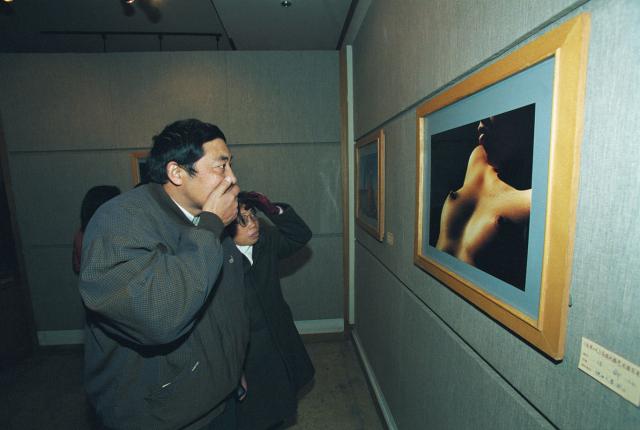

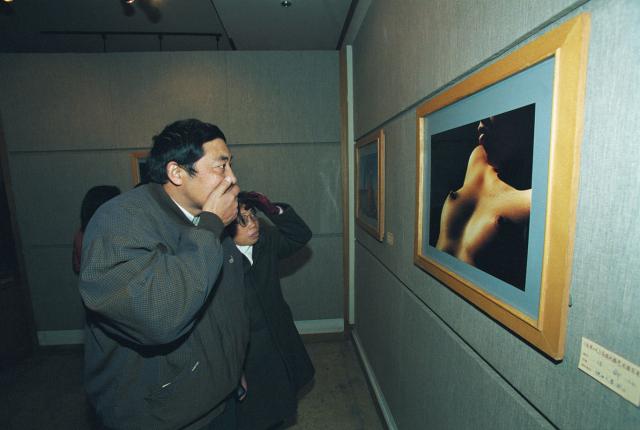

A visitor is apparently shocked by a photo of a woman’s breasts at an exhibition of nude photos, Xi’an, Shaanxi, December, 2000

Comrades in Arms

Kissing has not been an issue in China on screen or the streets since the 1990s. At least heterosexual kisses.

China had long forced the gay community to remain in the closet. The group has been specifically targeted since 1979. Homosexuality was also considered an act of hooliganism. Since the 1990s, the community has used tongzhi (“comrade”), a word with strong connections to communism, as a positive, gender-neutral term for self-description.

The first milestone for LGBTQ rights came in 1997 when hooliganism, including homosexuality, was no longer considered a crime, and in 2001 when it was removed from the official list of psychiatric disorders.

A number of gay films followed. Zhang Yuan’s East Palace, West Palace (1996), based on a short story by the late celebrated writer Wang Xiaobo, is China’s first film featuring a homosexual relationship.

The breakthrough film, which took home three awards at Argentina’s Mar del Plata International Film Festival, provided a realistic window into China’s gay communities, which previously had been disparaged in other mainstream films. Set in a city park frequented by gay men, the film tells a story of the evolving relationship between A Lan, a handsome writer in a heterosexual marriage, and closeted cop Xiao Shi.

Their first encounter occurs when Xiao Shi catches A Lan while patrolling the park. Without hesitation, A Lan steps up and kisses the policeman, a move that petrified Xiao Shi so much that he lets the writer stroll off into the night.

The second time Xiao Shi catches A Lan in the park kissing another man. This time, he takes A Lan down to the police station. A Lan spends the night alone with Xiao Shi revealing his fantasies and past as a gay man. He develops a masochistic infatuation with the cop and leads the closeted man to face his own sexuality.

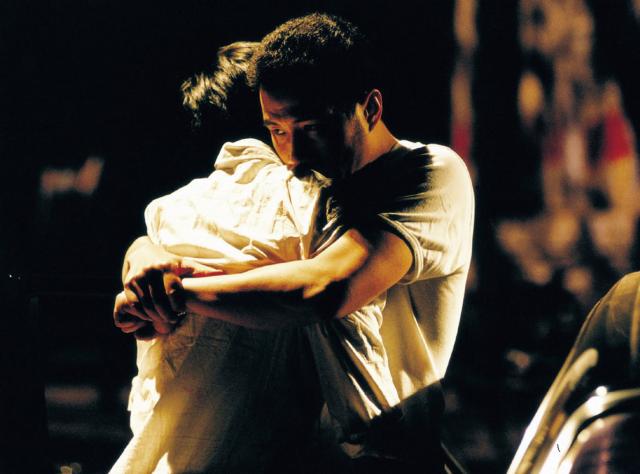

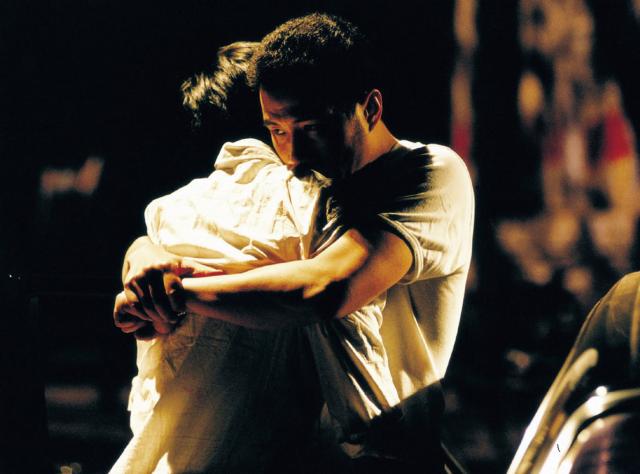

Award-winning indie film Lan Yu (2001) by Hong Kong director Stanley Kwan has achieved cult status in the Chinese LGBTQ community. Set in Beijing during the late 1980s-early 1990s, the film narrates a 10-year romance between Chen Handong, a successful businessman and son of a high-ranking Party official, and Lan Yu, a boy from the countryside now studying architecture. Lan Yu focuses on romance while challenging Chinese conventions with bold scenes showing passionate kisses, full frontal nudity and gay sex. The film won numerous awards worldwide, including two Golden Horse Awards for Best Director and Best Actor.

That same year also saw the Chinese mainland’s first film portraying lesbian relationships with Li Yu’s Fish and Elephant (2001). Qun, an elephant keeper at Beijing Zoo, seduces Ling, a woman who runs a clothing stall and is trying to escape from her violent ex-boyfriend.

The film realistically depicts sex between women and masturbation. In her small apartment, Qun reaches out to hold Ling’s hand, kisses her lightly on her lips, and moments later, the camera shows the two women embracing in bed, naked and facing one another. The final scene shows them passionately making love. The film earned wins at the Berlin International Film Festival and Venice Film Festival, among others.

Of course, it takes more than these films to completely change attitudes. While celebrated abroad, they are still banned at home. Over the past decade, the once-invisible LGBTQ community has garnered some positive attention in mainstream culture. By 2012, there were more than 100 LGBTQ organizations across the country. Indie LGBTQ filmmaking continues to thrive thanks in part to vanguard events such as the Beijing Queer Film Festival, which started in 2001 as the first LGBTQ festival in the Chinese mainland, and the ShanghaiPRIDE Film Festival held since 2015.

But China still has a long way to go. Conflicts between the increasingly open social attitudes toward sexual diversity and continuing State censorship are major challenges for LGBTQ filmmakers and activists.

Overall, China’s sexual revolution is no less spectacular than the economic miracle it created over the last four decades. Once shackled by sexual repression, Chinese society is slowly learning to engage in a growing dialogue about the diversity of love, sex and marriage.

And it all started with a kiss.

Lovers Chen Handong and Lan Yu hug in a scene from Lan Yu (2001)

The chaste kissing scene from the 1976 British film The Slipper and the Rose, published on the back cover of the fifth issue of Popular Cinema magazine, sparked huge discussions about public kissing in China in 1979

In July 1980, a Japanese singer, whose name was unknown, performed in China, wowing audiences with her dazzling clothing and appealing vocal and stage performance. Shows like this were banned during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76)

Old Version

Old Version