According to Jin, the official Putonghua used in modern literature more resembles an “artificial language” because it lacks the foundation of traditional culture that inspired the rich literary styles of the 1930s and 1940s.

Since 1956, the promotion of Putonghua helped overcome the regional communication barriers that linguistically separated China, increasing population mobility and accelerating economic development. But it also affected dialect use. Qian said that by the 1970s, use of Putonghua had become widespread. His daughter, who was born in 1976, would speak Putonghua at school and Shanghainese with family and friends. This bilingual environment continued until the late 1980s. In 1992, the Shanghai government banned primary and middle school students from speaking dialect at school. Broadcasters were forced to stop making television and radio programs in Shanghainese.

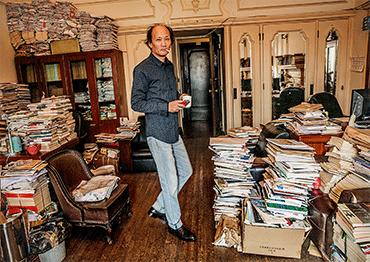

The rule lasted for over a decade, said Qian Nairong, and left most children in a sterile linguistic environment. “This means that for children born after 1985, there is a gap in the inheritance of the Shanghai dialect,” Qian added.

According to a survey of Shanghai students in 2012, only about 60 percent could understand and speak Shanghainese to varying degrees. The report, issued by the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, surveyed 21 primary school classes and 24 junior middle school classes in seven schools in Shanghai.

Chen Yanling, a professor at Quanzhou Normal University in Fujian Province, researched the use of dialects in Quanzhou’s urban and rural primary and middle school students in 2010 and 2011. Chen found that 24 percent of urban students spoke dialect.

Wang Lining, deputy director of the China Language and Resource Conservation Research Center, sees the trend as an unavoidable consequence of urbanization. Wang said dialectologists are not only concerned about the dramatic changes to China’s dialects, but also that some will disappear before they can be recorded.

At the end of 2018, Wang Lining and Cao Zhiyun, director of the China Language and Resource Conservation Research Center, led students to do field research into the She ethnicity dialect spoken in Tashi, Zhejiang Province. The She migrated from the coastal Guangdong and Fujian provinces to Tashi’s Dakeng Village over 14 generations ago. Today more than 140 registered residents claim She origins. Most under age 25 can speak little She dialect. Even though older villagers can speak She, most communicate in Wu.

Unlike most dialects in China, Cantonese has shown a unique resilience. Zhuang Chusheng, professor of the Chinese History Research Center of Zhejiang University, attributes this strength to the open and inclusive culture of Guangzhou. Many of the city’s natives strongly identify with their local culture and find pride in speaking Cantonese, Zhuang said.

When Britain colonized Hong Kong in the late Qing Dynasty(1644-1911), many from Guangzhou emigrated to Hong Kong. Cantonese, which is based on the Guangzhou dialect, soon became the city’s common tongue. After China’s reform and opening-up in the 1980s, migrant workers from across the country moved to Guangzhou. The province’s booming economy gave Cantonese the currency it needed to remain important. Music, film and pop culture from Hong Kong also arrived on the Chinese mainland, further cementing Cantonese’s influence.

But now, according to Wang Lining, fewer young people speak Cantonese. Wang added that even though major dialect populations seem stable, sub-dialects are on the decline. For example, the Cantonese dialect spoken in Dongguan, a city 50 kilometers south of Guangzhou, is rapidly disappearing.

Old Version

Old Version