Thanks to its special geographic position, Shanxi is the land where the cultures of northern ethnic groups and the zhongyuan mingled or met in conflict.

The Hu line, also known as the Tengcheng-Heihe line, stretches diagonally across China from the Yunnan-Myanmar border in the southwest, right up to the border with Russia at Heihe, Heilongjiang Province in the northeast. Identified by Chinese demographer Hu Huanyong in 1935, it demarcates a population density boundary where 94 percent of the country’s population lives east of the line, in warmer and wetter conditions better suited for agriculture. It also coincides with the 400-millimeter isohyet – a line of equal average precipitation. Land to the south and east of the line is agriculture intensive, while the region to the northwest mostly supports grazing. The section of the isohyet in Shanxi is further south than in other sections. In addition, the Yin Mountains to the north of Shanxi do not provide a sufficiently strong shield to repel invaders. These geographic and climatic conditions made it possible for northern nomadic tribes to march to the south.

In 200 BCE, founder of the Han dynasty Liu Bang led his army in battle against a joint attack force led by his rebellious general Han Xin and the Hun. But the Hun troops besieged him at Mount Baideng near today’s Taiyuan, capital of Shanxi. One of his officials, Chen Ping, proposed bribing the wife of the Hun chief Modu. The woman told her husband that more Han troops were coming and the Hun army was not strong enough to resist the enemy. The Hun chief Modu let Liu Bang go after seven days. In the following years, the Han had to send women of the royal family and treasures to the Hun chiefs to keep the peace. Even during this “marriage for peace” period, the Hun invaded the border areas from time to time. It was not until 81 years after the siege that the Han completely defeated the Hun.

In the 4th century BCE, China was in the Warring States Period (475 BCE-221 BCE), which preceded the first dynasty, the Qin. It was a time when seven powers fought each another for supremacy. One of them, the Zhao Kingdom, controlled part of today’s Shanxi and Hebei provinces and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. In 325 BCE, 15-year-old King Wuling ascended the Zhao throne. His kingdom was struggling under attacks from other powers and northern ethnic nomads. Fourteen years later, King Wuling learned from the northern ethnic nomads how to build a powerful army. He ordered his people to wear similar clothes to the northern ethnic groups with short sleeves, long pants and leather boots. These clothes were much better on battlefields than the wide robes with long sleeves that zhongyuan people wore. Zhao dignitaries resisted the policy, especially the king’s uncle, who resented absorbing lessons from their enemies. The king visited his uncle and persuaded him. The change was successful, and the Zhao got stronger.

More than 800 years later, an ethnic leader issued the opposite order. In the late fifth century, Tuoba Hong, known as Emperor Xiaowen of the Xianbei ethnic regime of the Northern Wei (386- 534), ordered everyone in his kingdom to wear Han clothes.

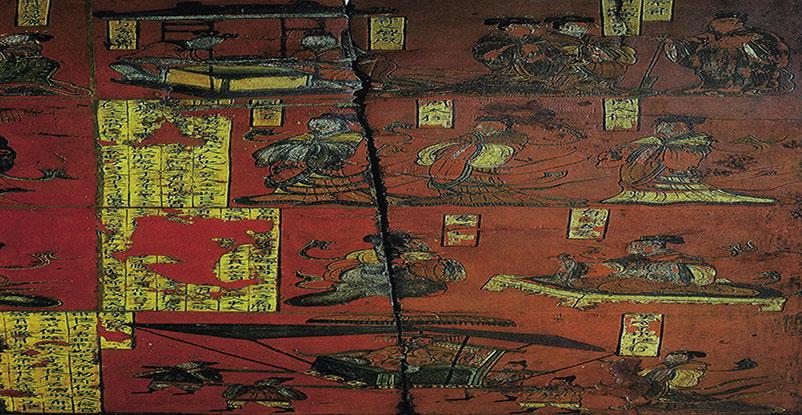

Starting in the early fourth century, several ethnic regimes controlled China’s north. The strongest was the Northern Wei kingdom of the Xianbei nomads. In 398, they moved their capital to today’s Datong in Shanxi from today’s Inner Mongolia. The site of their palace is on the national protection list.

Earlier Northern Wei emperors tried to accept Confucian culture to ease the tension between the Xianbei and Han peoples in the lands conquered by the Northern Wei. Many Han scholars served the Northern Wei. The third emperor of the dynasty, Tuoba Tao, even built a hall in Tatong to enshrine Confucius, where he often worshiped Confucius and the children of Xianbei and Han dignitaries studied Confucian classics. Agriculture was also restored and developed. The Northern Wei rose and defeated other ethnic regimes and united the north.

A sweeping reform on practicing Confucian governance and culture in the Northern Wei took place during the reign of the sixth emperor Tuoba Hong, who was raised by his grandmother, Empress Dowager Feng. Tuoba Hong ascended to the throne at age 5, so the power was in the hands of Feng. She adopted the political and economic system of the zhongyuan regimes. After she died in Datong, 24-year-old Tuoba Hong gained power and took over the reform.

The reform always faced strong resistance from Xianbei dignitaries. In 493, Tuoba Hong ordered his officials to march south with him to attack the Han regimes and unite China. After a tough month-long trek on muddy roads in constant rainfall, they arrived in Luoyang in Henan. The Xianbei officials did not want to continue the journey and petitioned to stop the march. Tuoba Hong pretended to be angry and asked his officials to choose between continuing the trek or settling in Luoyang. Most chose to settle. Indeed, it was Tuoba Hong’s plan to move the capital from Datong to Luoyang so he could push forward the adoption of Confucian rule.

The relocation was completed the next year. Tongba Hong then held a sacrificial rite in today’s Qufu, Shandong Province, the hometown of Confucius, an official demonstration that Confucianism was the orthodox ideology of the Northern Wei and that they were the legitimate rulers.

The north of Shanxi, including Datong, was controlled by the Liao kingdom (916-1125) which was established by Khitans in the early 10th century. Datong was the western hub of the Liao, the subsequent Jin kingdom (1115-1234) and the later Mongolian Yuan Dynasty (1206-1368). All were ethnic regimes. In the late 10th century, Xiao Chuo, a Liao empress, held power.

A popular TV series in 2020, The Legend of Xiao Chuo, depicted how she promoted reforms similar to the Northern Wei with the support of her husband, her son and Han Derang, a Han man with whom she had been in love since they were young. There is no confirmation in official historical records that Xiao and Han were in love, but there are records of the reforms they sponsored. For example, the Liao adopted the imperial exam system, which was started in the Sui Dynasty (581-618) about 400 years earlier. Agriculture was also encouraged under Liao rule.

In the mid-11th century, a Liao royal Buddhist temple called Huayan was built in Datong. The complex covered 66,000 square meters. It was destroyed and rebuilt repeatedly during successive ethnic and Han dynasties, including the Jin, Yuan, Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911).

In the 1960s, the temple became one of the first ancient sites on China’s national cultural heritage protection list. Huayan Temple combines the construction styles of the Liao with the earlier Tang and Song dynasties. Its main halls face east as the Liao worshiped the Sun, while Han buildings normally face south. The pagoda is a fully wooden structure which used the very strong mortise and tenon joints. The earliest such joint structure found so far dates back 6,000 to 7,000 years ago in today’s Zhejiang Province.

With recent severe weather damaging the remnants of Shanxi’s historical society, observers are now turning to how to better preserve and promote the culture that stems from this land. Further damage to the old buildings would be a great loss to China’s historical record.

Old Version

Old Version