lai’s Sichuan-accented Chinese bears a hint of frankness and humor.

Born in 1959 in Marerkang County of Aba Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Sichuan, Alai is one of the country’s most influential contemporary writers.

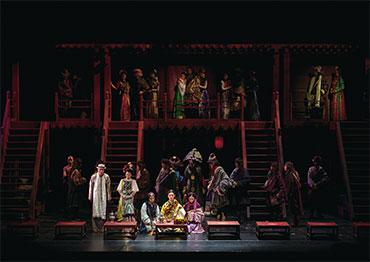

In 2000, his magnum opus Red Poppies won the fifth Maodun Literature Prize, China’s highest literary award, making him the youngest recipient at 41. A 20th-century epic with strikingly lyrical language, Red Poppies, narrated by a wise yet self-professed “idiot,” focuses on a Tibetan chieftain and his family during the final days of the local chieftain system. A three-hour stage adaptation debuted in Beijing on March 26, 2021.

Prolific and versatile, Alai has published poetry, short stories, novels and essays for nearly 40 years. His works have been translated into more than 20 languages.

The 62-year-old has not slowed down. In 2021, he was a judge for the 4th Blancpain-Imaginist Literary Prize, an influential Chinese literary prize for outstanding young Chinese-language writers.

In March 2021, the writer published the essay collection Keep Track of Time in Words, which includes articles about his reading, writing and traveling, to savoring liquor and remembering old friends.

Alai has always been a sharp observer of the country’s popular social and cultural phenomenon, from China’s literary cultural renaissance of the 1980s to the era of social media. He is concerned about the prevalence of internet slang and abbreviations, which he believes seriously affect people’s way of speaking, writing and thinking. Alai is vocal about his abhorrence toward what he views as the deterioration of the Chinese language online. “Human nature is always complicated. But sadly, we are turning back to a simplistic age,” he said.

NewsChina: In recent years, you have written more essays than fiction. Is it a change of focus?

Alai: It’s not a change. Fiction and essays are just two different mediums – fiction shows writers’ exploration of the world, while essays display their true selves. The essay is a more flexible form of writing that I prefer to use when I want to express the self that has not been “reformed” by media or some third party.

NC: Your fiction is highly lyrical and emotive. Was your writing influenced by literary trends during the cultural renaissance of the 1980s?

Alai: Not really. At the time I was living in a small place (Maerkang). That was a remote region far away from almost all the centers. Perhaps because of that, I was always a kind of distant observer. Chengdu was a cultural center at the time. Sometimes I went to Chengdu and spent a day or two drinking with friends, but I wouldn’t stay longer. There was a boom in literary and art societies in Chengdu, each advocating its own ideas. I told them I wouldn’t take part.

At first I wrote poems because I thought poetry was the purest form of literature, and also, comparatively speaking, the most accessible threshold to the literary world. But I had no intention of sticking with one single form. So I turned to fiction. People like to categorize writers as poets, essayists, novelists and playwrights. But such categorizations limit a writer. I first come up with a subject and then choose the form that fits it best. I don’t want to be tagged by any kind of identity – poet, essayist, fictionist or whatever. Just call me a writer. That’s OK.

NC: It has been over 23 years since Red Poppies was published. For decades, the book has been one of China’s best-selling literary works. Why do you think it resonates so much?

Alai: Perhaps there are some reasons behind its popularity. For instance, it has a very distinct language style. The words are lyrical, but in a very peculiar way. The lyricism has certain musical attributes, very melodious and rhythmic. Also, when readers finish the last page, they might feel the novel has touched on truths about human history. But I think it’s definitely not a book that blows its own horn from the first page, boasting “Look, I’m gonna tell you the truth about life.”

NC: In contrast with Keep Track of Time in Words, which took a highly critical and analytical tack regarding your thoughts on literature, your fiction is tremendously emotive. How do you write in such a lyrical and emotionally powerful way without being affected by critical thinking?

Alai: In ancient Chinese poetry, there is a concise saying that I think summarizes the principle of literature – “in poetry one expresses ideas, in their feelings grows poetry.” When reading, I try to analyze the meaning between the lines. But my own writing is naturally generated from my own strong, spontaneous feelings.

For me, writing has to be a happy thing. If I feel the impulse to write something, I don’t do it immediately, because I fear that is more of a whim. But if that impulse lasts for several years, then that is coming from the heart. When I start writing, I try to stay in a very good mood. Usually I write for three hours per day. If I get writer’s block, instead of exhausting myself at my desk, I go out and have a drink with friends or listen to a bit of Beethoven at home.

NC: You have been a judge for many Chinese-language literary prizes. What standards do you hold when evaluating the works of young writers?

Alai: Basically, I have two criteria. First, see how much that work relates to reality. Literature is not necessarily directly related to real life, but writers live in reality and we cannot escape from it. The second is to evaluate the artistic originality of the work, for originality is the essence of art.

In the past, I was quite depressed about the situation of contemporary Chinese literature, as the market was too occupied with pop fiction. Lots of writers have given up their artistic ambitions. The market forces are too great. For a long time, I mistakenly believed that millennial and Gen-Z writers have entirely given in to the market. But I was wrong. Being a judge of several literary awards gave me access to more works from young writers. I’ve been quite pleased that there are still many outstanding young people with strong artistic pursuits. But their works have been overshadowed by capital-backed popular trends.

NC: You’ve stressed a writer’s ability to examine reality in writing. Do you think young writers have done well on this point?

Alai: At least I can see they’re trying hard. Many of their works are very good indeed. The young generation has shown a conspicuous advantage over us – they are far better educated. They have a strong sense of aesthetics. When they began to write, they usually start with considering how to write more stylistically.

NC: You once said that millennial and Gen-Z writers have surpassed earlier generations in their ability to use the Chinese language. Why do you think this? Do you find any shortcomings in their writing?

Alai: It’s because the acquisition of language requires a systematic education. Young writers generally are better educated. Many have attended university. Some have a master’s or even a PhD. They are more intellectually well-rounded (than older generations).

As for the shortcomings... Perhaps they are too young and inexperienced. Of course, writing does not entirely rely on one’s personal experiences. But writers usually have broader and deeper social experiences than the general public. Young writers have spent too much time in school. Their lives are relatively simple and sheltered. But that doesn’t matter. People grow.

NC: As a Tibetan writer, have you ever been concerned that Han readers and literary critics might examine your work from an ethnocentric perspective?

Alai: This problem does exist. China has always been a multiethnic country. But nowadays people are increasingly embracing a shallow and narrow-minded nationalism.

Both Chen Yinque and Qian Zhongshu (two respected Chinese historians) stressed that the Chinese nation is not bonded by blood, but by culture. The power of Chinese culture is enormous. The reason that the country can cohesively merge different ethnic groups has mostly depended on its cultural attraction. Just as Confucius said: “If distant peoples do not submit [to your ruler], then enhance your moral refinement and charisma to make them come to you.”

In his book The Collapse and Expansion of China in the Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties, Japanese scholar Kawamoto Yoshiaki argues that the expansion of Chinese culture, particularly Han-centric Chinese culture, would peak whenever a political regime was on the edge of collapse. China had so many powerful ethnic minorities during the Wei, Jin, and Southern and Northern Song dynasties. Han people didn’t dominate them. They defeated Han regimes. Chen Yinque did some research and found that half of the family of Li Shimin, the second emperor of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), were Xianbei (a nomadic people). They just adopted Li as their Han surname.

NC: You have expressed concerns about the proper use of language. Do you think internet slang and abbreviations have influenced people’s everyday expression?

Alai: I pay little attention to internet slang and don’t like internet language either. I use the internet only to read news and e-books. Online libraries are a huge boon for me, because my home is already full of books.

In my opinion, the basic difference between humans and animals starts with speech, communication and writing – it’s the very demarcation between civilization and barbarism. Language evolves by its own aesthetics. It is only through language that humans are able to think critically and philosophically, and reflect on politics, economics, nature and all other spheres. If our use of language devolves to a primitive state as we use it only to blow off steam and never bother to think deeply, if the internet is awash with chaotic remarks from those who lack the ability to speak and think fairly and clearly, then we are returning to a savage age.

NC: There are never-ending battles of opinion on the Chinese internet. For instance, any issue concerning gender can start an online war between the sexes. Moreover, many abuse platform systems by flagging content to silence voices and even push for their accounts to be deleted. What do you think of this phenomenon?

Alai: The feminist movement has been going for several hundred years. In literature, ethics and economics, there are plenty of issues worthy of exploration and discussion, such as equal pay, equal opportunity, bodily autonomy and marriage.

But nowadays most debate on the Chinese internet is more about kneejerk reactions than sensible speech. The purpose of debate is to get us closer to the truth. But I see no point in most online debate. Mostly we only see two sides baring their teeth to berate each other. If this debate were meaningful, I’d like to take part. After all, writers write and give speeches to convey messages. However, right now the internet has deteriorated into a toxic environment where sensible communication and debate are almost impossible. Those willing to critically and calmly discuss topics will gradually be driven out.

NC: There is a tendency among Chinese readers to criticize and re-evaluate literature and arts from a moralistic perspective. For instance, young female readers tend to use the derogatory term zhanan (jerk, scum) to criticize any male character who by their standards is not faithful or responsible in a relationship. What do you think of this prevailing moralism?

Alai: After reform and opening-up (in 1978), the public began realizing that class and political labeling (such as an anti-revolutionary, a rightist or a spy) during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) was a brutally simplistic way to judge a person.

Human nature is always complicated. But sadly we are turning back to a simplistic age – at least that’s the case on the internet. In the present day, more and more people are taking the moral high ground and are quick to label those they believe are morally questionable. Zhanan is an example.

In the past, either in the West or the East, wrongdoers would be punished by laws or social rules, but they still had chances to turn over a new leaf. On the internet, however, it seems that those who are morally flawed are quickly judged and directly labeled with despicable marks. Moral judgment permeates all.

Old Version

Old Version