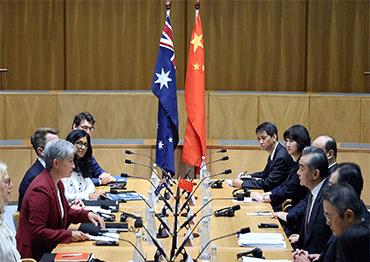

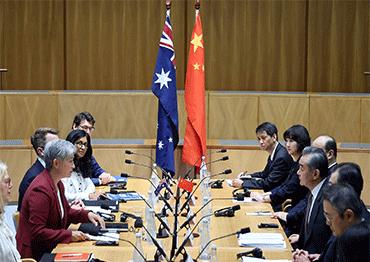

China’s Ministry of Commerce announced on March 28 that it would lift punitive tariffs on Australian wine. The decision was made one week after Foreign Minister Wang Yi, China’s top diplomat, paid a visit to Canberra, where he participated in the seventh round of China-Australia Foreign and Strategic Dialogues.

“China-Australia relations have returned to the right track,” Wang said during his visit on March 20, “There should be no hesitation, no yawing and no turning back, and bilateral ties should move forward.”

In his meeting with Wang, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese also expressed Australia’s commitment to deepening mutually beneficial cooperation with China across various fields. Emphasizing the importance of seeking common interests despite differences, he pledged continued efforts to foster constructive relations with China.

Following China’s decision to lift tariffs on Australian wine, Canberra swiftly responded by dropping its case against China with the World Trade Organization over the issue.

China-Australia relations have roller-coastered over the past 10 years.

Bilateral relations reached their zenith in 2014, when the two countries signed a free-trade treaty and announced a “comprehensive strategic partnership.” Australia also joined the China-initiated Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank in 2015.

But after Donald Trump assumed the US presidency in 2017 and started to adopt a confrontational policy toward China, the Australian government shifted its China policy, curbing investment from Chinese companies and accusing China of meddling in its domestic politics.

In 2018, Australia barred Chinese telecom giant Huawei from 5G contracts, making it the first country to do so. During the pandemic, then-Australian prime minister Scott Morrison called for a probe into the origins of Covid-19 and pressed China on its supposed responsibility for the outbreak.

In 2021, Australia canceled two agreements between China and Victoria state on the Belt and Road Initiative. Australia also joined AUKUS, a trilateral security pact with the UK and the US, to build and operate a class of nuclear-powered submarines. Australia also joined the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or the Quad, a diplomatic partnership including Japan, Australia, India and the US. Both initiatives are seen as targeting China.

Amid growing antagonism, China imposed “anti-dumping duties and antisubsidy duties” in 2021 on key Australian exports, including wine, barley, beef and lobster, and restricted coal imports from Australia.

After the Australia’s center-left Labor Party defeated the conservative LiberalNational coalition in the country’s federal election in May 2022, the Australian government led by Anthony Albanese started to adopt a less confrontational approach and sought to restore its relationship with China.

In November 2022, Albanese met with Chinese President Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the G20 summit held in Bali, Indonesia. In 2023, China gradually did away with restrictions on imports from Australia, beginning to lift unofficial restrictions on Australian coal in January, dropping the timber imports ban in May and punitive tariffs on barley imports in August, and removing a ban on meat exports from three Australian companies in December.

In November 2023, Albanese visited China, making him the first Australian prime minister to do so in seven years. During his meeting with Xi, Albanese pledged to “take forward” Australia’s relationship with China and to deal with differences “wisely and with great respect.”

Although the trade ties between China and Australia have been largely restored, a deficit in political trust between the two countries remains. While the Albanese government continues to embrace the Quad and doubled down on the AUKUS deal signed by the Morrison government, China has yet to entirely lift bans on Australian beef and lobster.

For many Chinese analysts, the fundamental problem of the China-Australia relationship is Canberra’s lack of independence from the US on its diplomatic and security policies.

“As a significant ally of the US, Australia’s diplomatic, security and economic policies have been deeply influenced by the US,” Ning Tuanhui, an assistant research fellow at the China Institute of International Studies, told NewsChina.

“The problem is that Australia’s interests do not always align with those of the US. Sacrificing its own interests to cooperate with the US in pursuit of the Indo-Pacific strategy aimed to contain China could be counterproductive for Australia.”

Unlike the US, which maintains a huge trade deficit with China, Australia has a large trade surplus with China. According to official data released by China, bilateral trade between China and Australia reached US$229.2 billion in 2023, with imports from Australia almost doubling exports to Australia. It is estimated that about 80 percent of Australia’s trade surplus comes from China.

Australian policy toward China should avoid being overly constrained and bound by the US,” Ning said. “Historically, the US has not always been considerate of its allies’ interests with China, and it can act unilaterally to serve its own interests, bypassing its allies.”

In recent months, many Australian politicians and scholars have called on the Australian government to adopt a more independent policy on China. A report released by influential Australian think tank China Matters titled “Can Australia and China have a stable relationship?” in November 2023 warned that the perception that Australia is incapable of pursuing an independent foreign policy and remains hostage to its alliance with the US will remain a major challenge to a long-term stable relationship between China and Australia.

Acknowledging that Australia will have to follow the US in strategic matters, the report advised that the Australian government could do more to hedge between the two powers in other areas, such as announcing cooperation initiatives and encouraging openness and exchanges.

Paul Keating, a vocal critic of Australia’s anti-China stance who served as Australia’s prime minister from 1991 to 1996, argued that the Australian government’s recent efforts to stabilize its relationship with China is far from enough. “The anti-China Australian strategic policy establishment was feeling some slippage in its mindless proAmerican stance and decided some new China rattling was overdue,” Keating said on March 5.

Keating’s comments were made during the ASEAN-Australia Special Summit held from March 4-6 in Melbourne, during which Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim reiterated his criticism of growing “China-phobia” in the West and stressed that Malaysia is “fiercely independent” and will not “be dictated to by any force” in its policy with China.

“Anwar is making it clear that Malaysia, for its part, is not buying US hegemony in East Asia – with states being lobbied to ringfence China on the way through,” Keating said, “That difficult task, the maintenance of US strategic hegemony, is being left to supplicants like us.”

Keating is also highly critical of the AUKUS agreement. In a statement released on March 15 last year, Keating said it was “a major mistake.” “A plan to spend around AU$368 billion (US$242b) for nuclear submarines to conduct operations against China in the most risky of conditions, is of little military benefit to anybody, even to the Americans,” Keating added.

By signing the AUKUS deal, which he described as “an American sword to rattle at the neighborhood to impress upon it the US’s esteemed view of its untrammeled destiny,” Keating said that the Albanese government has “screwed into place the last shackle in the long chain the US has laid out to contain China.”

After the US announced in March this year that it would halve the number of submarines it would build next year, even many hardliners started questioning the wisdom of the AUKUS deal. Malcolm Turnbull, another former Australian prime minister who served from 2015 to 2018, told the media that Australia has been “mugged by reality over the AUKUS submarine deal.”

Pointing out that the US is struggling to ramp up production of its own submarines and maintain the submarines it already has, Turnbull, who declared in 2017 that Australia would “stand up” to China, warned that AUKUS could make the country completely dependent on the US for its future defense.

In a speech addressed to the Australia Defence College on March 15, Turnbull reiterated that he is “very concerned” that Australia’s acquisition of nuclear submarines could jeopardize the country’s sovereignty, as the country’s lack of expertise in the field means that Australia would not be able to operate the submarines without the cooperation of the US.

“The AUKUS submarine plan will see many billions of Australian dollars being invested in American and British submarines and submarine-related infrastructure,” Turnbull said. “It will be seen as making us even more dependent on the US and now the UK.”

Australian officials have long denied that the nuclear submarine deal is targeted at China. In March 2023, when asked by media whether Australia had given the US any commitment to help during a potential conflict over Taiwan, Australia’s Defense Minister Richard Marles said there was “absolutely not” a quid pro quo obligation on Australia for the deal.

But on April 3, US Deputy Secretary of State Kurt Campbell directly and publicly linked AUKUS with the Taiwan question, which made many Australians uneasy. Speaking with a Washingtonbased think tank, Campbell said the AUKUS deal’s submarine capabilities “have enormous implications in a variety of scenarios, including in crossstrait circumstances,” referring to the Taiwan Strait. Campbell’s comments cast further doubts on Australia’s autonomy over its future submarine deployments.

For many Australian politicians and experts, instead of aligning itself with the US over its containment policy against China, Australia should take a more constructive role in promoting peace and cooperation in the region. In January, 50 prominent Australian diplomats, academics, writers and activists, including Bob Carr, former foreign minister and former premier of New South Wales, and Gareth Avans, former foreign minister and honorary professor at The Australian National University, signed a public letter calling for Australia to adopt “an activist middle power diplomacy.”

Warning that the US-China confrontation could “lead to direct military conflict, which would risk dragging Australia into war,” the signatories said they support a balance of power in the Indo-Pacific region in which “the US and China respect and recognize each other as equals” with “neither side demanding absolute primacy.”

“We call for Australia to support the goal of détente – a genuine balance of power between the US and China, designed to avert the horror of great power conflict and secure a lasting peace for our people, our region and the world,” reads the letter.

To a large extent, the letter converges with what China’s Foreign Affairs Minister Wang Yi proposed when he was in Australia. Stating that the two countries should continue the positive momentum of the bilateral relationship to “work together for the future,” Wang said that the two countries should jointly build “a more mature, stable and fruitful” relationship.

“Independence should also be an important principle of Australia’s foreign policy. The development of China-Australia relations does not target any third party, nor should it be influenced or disturbed by any third party,” Wang said.

Old Version

Old Version