The 2,500-year-old legacy of China’s legendary father of carpentry continues as workshops bearing his name help foster thousands of skilled professionals in developing countries around the world

On February 26, 2024, Kazakhstani President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev visited the Luban Workshop at East Kazakhstan Technical University during his tour of eastern Kazakhstan. The visit attracted media attention in Kazakhstan and China because it coincided with the workshop’s anniversary.

Luban Workshop is a Chinese international vocational education project that aims to help developing and other countries train skilled professionals. First established in 2016, the project has offered degree education and vocational training to over 14,000 individuals in more than 20 countries including Thailand, the UK, Portugal, India, Pakistan, Ethiopia and Egypt.

The Luban Workshop in Kazakhstan was initiated in March 2023 when China’s Tianjin Vocational Institute and East Kazakhstan Technical University signed a memorandum of understanding for cooperation.

As a landlocked country with a widely dispersed population, Kazakhstan has a significant need for dependable land transportation. However, development of the country’s automotive industrial chain and training of professionals have lagged behind. In recent years, Kazakhstan’s government has intensified its focus on new-energy vehicle (NEV) development plans, creating a pressing demand for skilled NEV maintenance technicians.

The Luban Workshop curriculum is designed to meet that demand, including 20 courses covering vehicles with internal combustion engines, NEVs and smart vehicles.

Mortise and tenon joinery in Bao Guo Temple, Zhejiang Province, April 13, 2023

A volunteer demonstrates a Luban locking puzzle during an intangible cultural heritage event in Zhengzhou, Henan Province, April 14, 2021 (Photos by VCG)

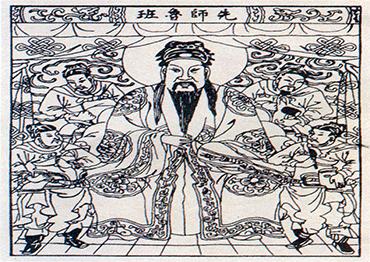

Wooden Horses & Birds

The workshop is named after Lu Ban, China’s “father of carpentry.” According to legend, Lu Ban was born in 507 BCE to a long line of carpenters. It was the late Spring and Autumn Period, a time plagued by political chaos and instability from wars among neighboring states. Lu Ban’s original surname was Gongshu, but since his family lived in the State of Lu in East China’s present-day Shandong Province, he became known as Lu Ban.

From a very young age, Lu Ban joined his relatives in construction projects and gradually mastered the family trade. He was also keen on inventing new tools to enhance work efficiency.

According to folklore, his inventions included the saw. Carpenters at that time used axes to carve and shape wood, a time-consuming process that led to imprecise results. One day while Lu Ban was chopping down a tree in the mountains, he accidentally cut his finger on a leaf. The blood quickly trickled down his hand, and he wondered how a single leaf could be sharp enough to cut through his skin so easily. He took a closer look and noticed its serrated edge. It dawned on him that a jagged-edged metal tool could make cutting wood much more efficient. After many experiments, Lu Ban created a saw.

Lu Ban was also known for inventions that revolutionized warfare and transportation. He is said to have invented the “cloud ladder,” an extendible ladder on a wheeled platform for attacking walled towns in siege warfare, and a grappling hook-ramming weapon for capturing enemy ships and breaking through their defenses.

Historical records also credit him for inventing fantastical devices, such as a self-propelled vehicle called the “wooden horse” to help transport heavy military supplies over long distances and a flying “wooden bird” that could stay airborne for three consecutive days.

In addition, Lu Ban is credited with building many bridges and palaces. Some of his techniques and projects are recorded in The Treatise of Lu Ban, a book of carpentry and folk culture from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

Many Lu Ban inventions are still used by Chinese carpenters today, such as a line marker similar to a chalk line, and the Lu Ban ruler with segments to help calculate auspicious measurements according to feng shui principles.

Of course, historians and archaeologists point out that Lu Ban is likely a folk amalgamation representing the innovations of his time. Archaeological evidence indicates that saw-like tools appeared as early as the Neolithic Age, when early humans used jagged-edged stone and clamshell sickles. A character for “saw” was already in use during the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE), centuries before Lu Ban was born.

Global Influence

Nevertheless, Lu Ban’s legacy is reflected in the numerous temples and shrines dedicated to him throughout the country. The largest memorial hall is located in his supposed hometown of Tengzhou, Shandong Province. Craftspeople in the construction industry still celebrate Lu Ban’s birthday, the 13th day of the sixth month of the lunar calendar, when they conduct rituals in temples and shrines to pray for their work in the coming year.

Lu Ban’s cultural legacy has found its way into folk stories, dramas and even idioms. One of the best-known Chinese idioms is banmen nongfu, which literally translates to “displaying one’s skills with an axe in front of Lu Ban’s door.” It is often used to refer to anyone who shows off mediocre skills in the presence of a master. The story goes that one day, a young man showed up in front of Lu Ban’s house waving his axe and calling himself an expert axe-handler. People pointed at Lu Ban’s door and asked the young man whether he could make a door just as exquisite. The young man bragged, “Let me tell you, I’m a student of Lu Ban, so I can make a door 50 times better than that one.” The people laughed and told him there is no way he could be Lu Ban’s student because he did not recognize the master’s house.

Another well-known Lu Ban phrase is youyan bushi taishan, “to have eyes but fail to see Tai Shan.” It is said that Lu Ban was very strict with his students and would dismiss those who did not work hard or meet his standards. He expelled one of his students, a young man called Tai Shan, citing his lack of improvement. Years later, Lu Ban came across several pieces of well-made furniture in a market and asked who made them. He was shocked to learn that it was the very same Tai Shan who he had kicked out of class years before. Lu Ban felt ashamed and sighed, “I was too arrogant to recognize Tai Shan.” Today, the phrase is used to describe a person who fails to recognize talent.

Lu Ban has become a symbol of innovation and excellence in construction and engineering, and his contributions have been recognized through honors and awards, including the China Construction Engineering Lu Ban Prize, a national award given to quality projects.

Lu Ban’s influence has extended beyond China. In 2014, during his visit to Berlin, former Chinese premier Li Keqiang presented a handmade Lu Ban locking puzzle as a national gift to former German chancellor Angela Merkel. Made from seamlessly interlocked wooden blocks, Lu Ban puzzles challenge players to discover how they connect, take them apart and reassemble them. With this gift, Li said he hoped the two countries could resolve their differences intelligently and expand their future cooperation.

More than two millennia after Lu Ban’s time, Luban Workshops follow his spirit of craftsmanship and have become a bridge of friendship through cultural and educational exchange. By providing needs-driven vocational training programs, the workshops enable individuals in participating countries to chart a new path to economic and social development.

A teacher and students during a training program at the Lu Ban Workshop in Tajikistan, April 17, 2023 (Photo by VCG)

Old Version

Old Version