Trailblazing female archaeologist Zheng Zhenxiang (1929-2024) pioneered research into China’s Bronze Age civilizations, with her seminal discovery of the tomb of the first Chinese female general inspiring generations of archaeologists

On March 14, archaeologist Zheng Zhenxiang (1929- 2024), a leading expert in the Bronze Age Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE) passed away at the age of 95 in Beijing. Zheng, through her meticulous research and focus on field excavations, discovered in 1976 the tomb of Fu Hao, a queen and China’s first known female general, who lived around 1200 BCE. Archaeologists and historians paid tribute to her dedication to exploring and researching Bronze Age cultures in China, and for inspiring new generations of archaeologists with her meticulous focus on field work.

Tang Jigen, chair professor of archeology at Southern University of Science and Technology and former researcher at the Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, was one of Zheng’s graduate students. He told NewsChina in March that her life was dedicated to archaeological research. “She worked in the field for such a long time that her trowel was worn down to the size of a small teaspoon,” Tang said.

Zheng was born in 1929 in northern China’s Hebei Province in a normal family. After she graduated from Tianjin No.1 Normal College in 1950, she was admitted to the museum department of Peking University, and after studying there for two years, she became the only female college student enrolled in the new archaeology major at the university, the first such course in the country.

After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in archeology, she taught at the university. In 1954, her interest in oracle bones led her to pursue her lifelong focus on researching Bronze Age dynasties, the Shang and the subsequent Zhou (1046-256 BCE).

When she graduated with a master’s in archeology in 1959, encouraged by her tutor, Professor Pei Wenzhong, a famous Paleolithic archeologist and paleontologist, Zheng chose to join the Institute of Archaeology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences (now the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences). She immediately moved to Anyang, Henan Province to work in the field at Anyang Archeological Station.

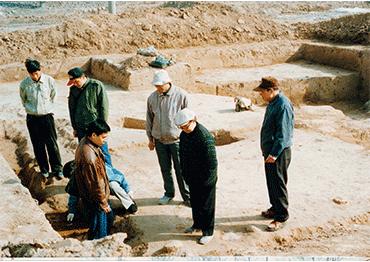

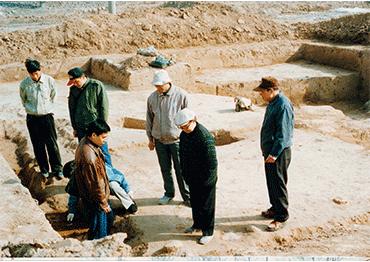

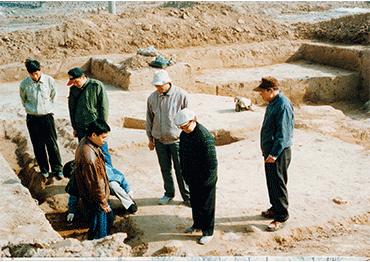

Zheng Zhenxiang (second from right) and her colleagues look at an excavation of Shangera houses, Anyang, Henan Province, May 1997 (Photo Courtesy of Interviewee)

Groundbreaking Discovery

Anyang, the site of the capital of ancient Shang Dynasty known today as the Yinxu Ruins, was fertile ground for archaeological research and one of the cradles of Chinese civilization. After becoming deputy head of Anyang’s archaeological team in 1962, she devoted the rest of her professional life to studying and excavating the Yinxu Ruins. “Archaeologists who don’t work in the field are like opera singers who don’t perform on the stage. Such archaeologists won’t make achievements,” Zheng would say.

She met her husband Chen Zhida, also an archaeologist at Anyang, and they married in 1968. The couple had no children, and Chen passed away in 2017.

The discovery of Fu Hao’s tomb was an accident. In late 1975, a nationwide agricultural campaign was launched to increase farming output. Farmers were encouraged to flatten hills and dig irrigation systems. The location of Fu Hao’s tomb was a highland area in Xiaotun Village, which farmers were supposed to flatten. Although the area had not been investigated, it was thought to be the palace and temple area of the Yinxu Ruins, and was set aside as a protected area.

When Zheng learned of the plan, she commenced exploratory digs on the foundations of two Shang-era buildings. They shoveled earth by hand all day, but only found tightly packed soil to a depth of five meters. Some suggested the efforts would be fruitless, but Zheng persisted. Claiming there was “no such thing as a bottomless pit,” she continued digging.

At a depth of seven meters, a probe hit empty space. As it dropped, everyone held their breath until it hit the bottom at 7.5 meters down. When a worker carefully lifted it out, there was evidence of bright red paint. Another returned with a jade pendant.

It was a magnificent discovery. Most of the area’s tombs had been robbed long ago. Zheng’s team raced against time and the water table, which risked flooding the site before it could be properly excavated. In just 20 days, Zheng and her team uncovered over 210 bronze vessels, 750 jade objects and hundreds of bone fragments. The bronze instruments alone weighed over 1.6 tons.

But what excited Zheng the most was an inscription saying “Fu Hao” or “Hao,” the name of the tomb’s owner on 109 bronze vessels. Before the tomb was found, the name “Fu Hao” had appeared hundreds of times inscribed on oracle bones already found at Yinxu. Thanks to Zheng’s study of oracle bones at Peking University, she knew the story of Fu Hao, a queen during the Shang Dynasty and the first woman general in Chinese history. Fu Hao was the consort of King Wu Ding, the 23rd ruler of the Shang, who was in power around 1200 BCE, the same time as the late Babylonian period. She was also a priestess who presided over sacrificial ceremonies and a general who led military campaigns.

“I knew the story of Fu Hao when I studied at Peking University. When I saw her name on the bronzes, I felt shock and inexpressible joy. Unearthing Fu Hao’s tomb is the biggest thing I have done in my life. I hope people will learn more about cultural relics and the history and culture behind them,” Zheng told online news platform Changsha.cn in 2007.

Thus, Fu Hao, the queen and female general of the Shang Dynasty who had slept for over 3,200 years underground, was “awakened” by Zheng, one of the first generation of female archaeologists in China. The tomb contained 1,928 burial objects, more than all the artifacts previously unearthed in Yinxu.

The tomb of Fu Hao is the only intact tomb of Shang Dynasty royal ever found, and the only tomb whose owner and date can be determined according to corresponding inscriptions on oracle bones. It is one of the most important archaeological discoveries in Yinxu. She also posited there were other tombs linked to Fu Hao’s relatives in the area, which proved correct.

The relics of the Yinxu Ruins, including from the Fu Hao tomb, can be directly connected to the Shang Dynasty, so they are of great significance. “In several of her papers, Professor Zheng clearly explained the academic value of Fu Hao’s tomb,” Tang Jigen told NewsChina. “In the past, people knew Zheng more because of her success in excavating the Fu Hao tomb, but she also contributed a lot to the wider research [on the Shang].”

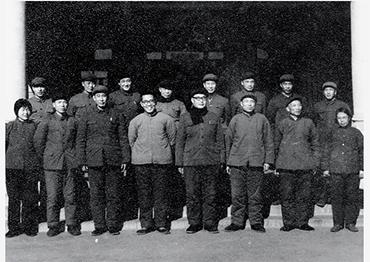

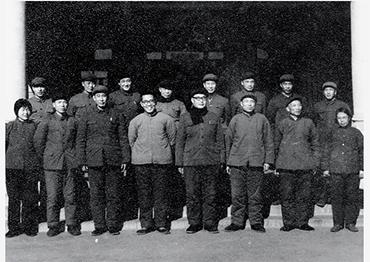

Zheng Zhenxiang (first from right) and her colleagues with the Institute of Archaeology, the Chinese Academy of Sciences in the 1960s (Photo Courtesy of Interviewee)

Simple Lifestyle

Yue Hongbin, a researcher at the Institute of Archaeology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, remembers seeing Zheng Zhenxiang’s office when she started working at the institute in the early 1990s. The office was in an old building in Beijing. “It was dark and poky, packed with books,” Yue told NewsChina.

Zheng spent most of her time in Anyang. The night before she would journey by train back to Anyang, she slept in her office stretched out on two chairs to get an early start on the 10-hour journey.

Guo Peng, who works at the History and Archaeology Publishing Center, China Social Sciences Press, worked with Zheng at Anyang in the early 1990s. He marveled at her strength. Every morning, she carried her canvas bag of tools to the dig site. After lunch, she rested for a short while, before working until sunset. “I was in my 20s, and working a whole day was really painful. Professor Zheng, in her 60s, was persistent and I could feel the strength she had inside her,” Guo told NewsChina.

To this day, Tang remembers his first meeting with Zheng in Anyang. “It was the winter of 1986 and I was just a young aspiring archaeologist, in awe of the master sitting in front of me. Looking around her room, I was struck by how simple everything was, from the slightly stiff quilt atop her simple wooden bed to the heavy and mottled writing desk with its lacquer peeling off in places. A pool of fresh wax was visible on the surface, evidence of another late-night reading by candlelight; I could feel the icy wind seeping through the cracks in the brick,” Tang wrote in an article published by online news portal The Paper in late 2021.

Leading up to her retirement, she worked on field excavations and research for seven months a year. Her students recall her dressing simply, in a threadbare T-shirt in the summer, and dark blue or dark gray overcoat in the winter. She usually wore a beat-up straw hat in the field, that she sewed up time and again.

Retiring from fieldwork and the research institute in 2003 at 73, Zheng devoted the remainder of her career to publishing her findings and mentoring young archaeologists. She compiled her findings and discoveries and published another two books. Yue Hongbin told the reporter that whenever he met Zheng in Beijing, she always questioned him about the progress at Yinxu.

Quilts, an enamel cup, a flask and other daily items Zheng Zhenxiang used when she worked at excavtions, Anyang, Henan Province (Photo Courtesy of Tang Jigen)

Academic Openness

For many years, Chinese historians and archaeologists agreed the Shang should be split into two eras, the early Shang, represented by the Shang city excavated in Zhengzhou, also in Henan, and the late Shang, represented by Yinxu. Zheng was also of this opinion.

In 1982, when Tang Jigen studied archaeology at Peking University, he was taught this theory. But he felt the connections between the two Shang sites was not proven.

While reviewing photos of pottery excavated from both sites, he felt some of the patterns and shapes did not belong to either the early or the late Shang. He discussed his theory with Zheng, and told her he wanted to investigate the relationship between the two sites.

Zheng encouraged Tang to explore his theory. In his graduation thesis, Tang concluded “there is still a certain period of time between the early Shang-era culture represented by the Zhengzhou Shang city ruins and the late Shang-era culture represented by the Yinxu Ruins.” He proposed that part of the Yinxu Ruins and another archaeological site at Xiaoshuangqiao in Zhenghou, Henan Province, should be belong to a new era that he called the mid-Shang culture. Initially, Tang worried his ambitious view might be in opposition to Zheng’s academic view. But she supported him in his thesis defense. “I know it’s not so easy. Professor Zheng’s generosity shows her demeanor as a true model scholar.” Since 1993, thanks to Zheng’s support, Tang has published several articles based on his thesis.

Tang remains impressed by his teacher’s academic openness. “If it weren’t for her academic selflessness and support, I likely wouldn’t have focused on field excavations to search for artifacts from the mid-Shang era, and the later discovery of Huanbei Shang City [the northeast part of the Yinxu Ruins Protection area] might not have been possible, let alone the concept of the ‘mid-Shang era,’” Tang said.

It is common among young scholars nowadays to see theories about the Yinxu Ruins as having developed organically. According to Tang, Zheng started adding time parameters into her writings that depicted the layout of the Yinxu Ruins as early as the 1980s.

“At that time, most scholars categorized the Yinxu Ruins into discrete areas, like the palace and the royal mausoleum, but Professor Zheng had already taken time into account. For example, she would state that during the first phase of the Shang Dynasty, the people lived here, then say where they expanded to live during the second stage, and that there was a population boom during the third stage. It allows us to see the layout of the Yinxu Ruins not within just a limited spatial framework, but as a dynamic process,” Tang said. “Following a clear historical timeline, the architectural layout keeps evolving and changing, and the Yinxu Ruins have become three-dimensional and multi-dimensional. This was a very advanced perception at that time, which greatly influenced and inspired us younger researchers.”

In honor of her work, Zheng was dubbed “archaeological female general,” but she refused to accept the name. “I’m an ordinary archaeologist who can’t compare with General Fu Hao. Fu Hao could lead 13,000 soldiers to war, but I can only guide a hundred workers to excavate tombs,” joked Zheng when she appeared on TV show National Treasures on China Central Television in December 2017.

Spending over 40 years in Xiaotun Village, the residents all knew Zheng. They called her Lao Zheng (Old Zheng) just like their fellow farmers, not Professor or Madam Zheng. Yue Hongbin said whenever he thinks of Zheng, he pictures her wearing her old straw hat and carrying her small bag filled with tools toward the site in Yinxu, the place where she worked diligently for half her life.

Old Version

Old Version