While livestreamed classes have helped students in poorer, rural areas gain access to top resources, long-distance education alone does not narrow the urban-rural education gap, experts say

In early December, China Youth Daily reported that 88 students from impoverished areas in Southwest China’s Yunnan Province had been accepted to some of the nation’s top-tier universities – thanks in part to teachers hundreds of kilometers away.

In place of their own curriculums, rural schools were sitting students in front of screens to attend livestreamed classes from Chengdu No. 7 High School – one of the nation’s top rated.

In 2002, Chengdu No.7, in Chengdu, capital of Sichuan Province, began broadcasting its curriculum via satellite feeds as part of a remote education project for rural areas in partnership with Chengdu-based internet technology company EastEdu. Since then, 72,000 students at 248 schools have attended these remote classes. Most schools reported a dramatic rise in university enrollment rates. Last year, three students from Luqua No.1 High School in mountainous Luquan County in Yunnan were accepted to Peking and Tsinghua universities, with a majority of their graduating class going on to college. The school hadn’t seen such high enrollment in 30 years, Luquan No.1’s principal told the paper.

But as livestreaming garnered public support for its contribution to narrowing the education gap between urban and rural areas, dissenting opinions also mounted.

Critics attributed the enrollment surges to preferential policies for students in poverty-stricken areas. Furthermore, they argued that the effectiveness of remote education depends more on individual students and teachers rather than the method itself. Others raised concerns that the media hype surrounding it drew attention away from the underlying, more serious problems in rural education.

“I never thought I was so behind [urban students],” Wang Yihan, a freshman at Luquan No.1 High School told China Youth Daily. According to the report, she scored highest in her town on the national high school entrance exam in 2018. She also was top of her math class. However, Chengdu No.7’s livestreamed classes laid bare the enormous gap between rural and urban students. She failed all but one of the school’s midterm exams, including math.

Window to Inequality

Wang’s experience was common among the Luquan students who took Chengdu No.7’s livestream classes for the first time. As the teachers on screen discussed lessons and interacted with their students in Chengdu, many in Luquan were at a loss. Though top students at their school, some told China Youth Daily they had never heard of the concepts being discussed, let alone understood them.

However, the rural students’ scores on the Chengdu No. 7 exams suggest this gap is closing.

Despite the nationwide trend of high performing rural students heading for provincial schools to better their chances at getting into university, Luquan No.1 saw 147 students enrolled in first-tier universities. Another 634 were accepted to second-tier schools.

“Livestream classes have given [underprivileged] students a window to the outside world and goals to strive for,” Wang Hongjie, founder of EastEdu, told China Youth Daily. “These students have unlimited potential that has yet to be explored,” he added.

In 2000, the Sichuan provincial government issued an action plan to improve education in predominantly ethnic minority regions, and remote education was defined as a key response. In addition to schools in poverty-stricken areas in other provinces, Chengdu No.7’s classes were also used by non-key high schools throughout Sichuan.

“The livestreamed teachers impressed me with their wealth of knowledge and their enlightened teaching skills. It encouraged me to study even harder,” Zhang Juchuan, a college student in Sichuan who attended livestreamed classes during junior high school, told NewsChina. “I agree that it’s a chance for underprivileged students to change their fates, since [most of] them are more strong-willed [than urban students] and you cannot imagine how thirsty they are to learn.”

Out of the Screen

“Changing Fate” was the headline of the China Youth Daily article that evoked sympathy from the public. Many felt internet technology would become an effective way of narrowing regional education gaps. At the same time, the headline sparked controversy. Many called the article misleading, accusing it of exaggerating its benefits while ignoring other important factors, such as local teachers.

Xiong Bingqi, deputy director of the 21st Century Education Research Institute, believed that the improved enrollment rates were largely based on China’s preferential policies for underprivileged

students. Under the policies enacted in 2012, top universities are required to meet a quota of students from specified areas. According to the Ministry of Education, the student quota from the national program increased from 10,000 in 2012 to 63,000 in 2017.

In 2017 alone, first-tier universities, due to national and local preferential programs, enrolled 100,000 students from target areas, a 9.3 percent increase on 2016. In addition, the government has been expanding university enrollment nationwide since 1999. According to Xiong, China’s tertiary education enrollment rate climbed to 45.7 percent in 2017, compared to 15 percent in 2002.

“It is unreasonable to completely attribute underprivileged students’ enrollment in top universities to remote education or livestreamed classes. Instead, I believe national policies play a leading role,” Xiong told NewsChina, adding that livestreamed classes deprive students of real, classroom interaction with teachers.

Chu Zhaohui, a researcher of National Institute of Education Sciences, echoed Xiong’s concerns. “It should be noted that livestreaming is only a tool, and its effect depends on how we use it,” he told NewsChina.

Remote education in China is nothing new. Wang Hongjie said it was online courses provided by Beijing 101 Middle School, a key school in the capital, which inspired him to start EastEdu in 2002. The difference is, while online courses previously served as supplementary teaching, Wang replaced local curriculums altogether with Chengdu No.7’s livestreamed classes. The move caused concerns among experts that the public would see livestreaming as a solution for shortages of qualified teachers in poorer areas.

“Local teachers actually play a bigger role [than remote teachers] in livestreaming classes because they have to help the students digest the lessons and explain difficult points. This requires [local] teachers to quickly grasp all the essentials of each livestreamed class,” Luo Dacheng, a local teacher at Lezhi County Wuzhongliang Middle School, Sichuan Province, told NewsChina.

Zhang Juchuan agreed. He recalled how local teachers reinforced the lessons from each livestreamed lesson. “The classes were actually too advanced for many of the students, so we needed our teachers to help us. A drawback of the livestreamed classes was that the remote teachers couldn’t interact with us. They were blind to the true level of the students on the other side of the screen,” he explained. “So, a prerequisite for ‘changing fate’ is that students have local teachers to help solve any problems they have with the concepts,” he added.

This idea is supported by an article from social media news outlet idaxiang, which interviewed a number of students in Daliangshan, a poor region of Sichuan. The students said livestreamed classes at their schools have left many unable to keep up without local teachers to help. Wang Yue told idaxiang that local teachers were shirking their responsibility. “Our teachers were not as active as the teachers at Luquan No.1 High School and they seemed to have no idea how to help us with the classes,” he said.

“That doesn’t come as a surprise,” said Cao Xuelin, a former volunteer teacher in Daliangshan. “Things would have been totally different if reporters had interviewed teachers and students at other schools in the same area,” Cao said. “Based on my experience at Daliangshan, teachers vary dramatically, especially between key and non-key schools,” she added. According to the China Youth Daily report, some teachers at Luquan No.1 protested by tearing up textbooks because they felt the use of livestreamed classes demeaned their abilities.

Han Peiyu, an elementary school teacher in an impoverished county in Gansu Province, welcomes the opportunities remote education brings. He told NewsChina that his school has introduced online courses for English and art through two charity programs. He found that the two courses have greatly improved both the students and the teachers. “We teachers in underprivileged areas receive little training, so online courses can be a simple, effective alternative,” he said.

This is what concerns some experts. “It is negligent of the authorities to simply use online courses to develop local teachers. Training is much more complicated and costly,” Xiong said.

Chu agreed. “In the end, the key to narrowing the education gap lies in the development of local teachers.”

Fate and Fairness

According to Luo Dacheng, livestreamed classes cost between 60,000 and 70,000 yuan (US$8,696-10,145) per classroom per year, not including special equipment. Many local governments simply cannot afford it.

Also, only the best students are able to keep up with the Chengdu No.7 classes. In Yunnan Province, for example, an average of 18 students per school took livestreamed classes annually, China Youth Daily reported. Similarly, both Luo and Zhang’s schools could only provide two classes per grade with livestreamed lessons.

Although many, including Zhang, say it’s fair to screen students with exams, experts worry this would lead local governments in poorer areas to prioritize a small group of more promising students over the larger student population.

One middle school in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, for example, reportedly selected 35 top students to attend livestreamed classes and assigned them the school’s best teachers. The group of students also enjoyed the school’s only air conditioner and a separate dining hall.

“It may result in more unfairness if limited resources favor only a small group of people,” Chu warned.

Xiong Bingqi also expressed concerns about the recent media attention on remote learning. “It’s true that the national college entrance exam [gaokao] is the only ticket out of poverty for underprivileged students, but I don’t think that exams are a sustainable solution for alleviating issues in rural education, since it only benefits a small portion of people,” he said. “We must also remain aware as to the large number of rural students quitting school,” he added.

Xiong’s arguments are supported by data from the Ministry of Education that shows the number of students attending elementary and middle school in China’s rural areas has dropped by 15 percent from 2013 to 2017. The number of trained rural teachers also similarly fell over the same period.

“In economically depressed areas, only a very small number of students go on to university. For most, migrant work is the only way out. So, many students quit school as soon as they finish their nine years of compulsory education,” Wang Jing, an elementary school teacher in a poverty-stricken county in Yunnan Province, told NewsChina. “To tell the truth, many people here have no ambitions of getting into university,’” she added.

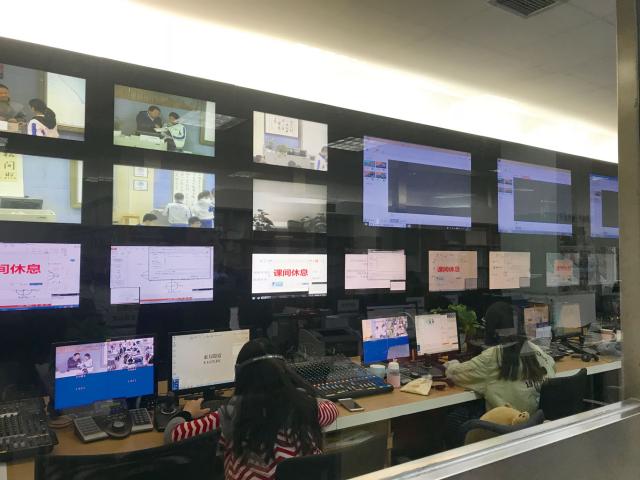

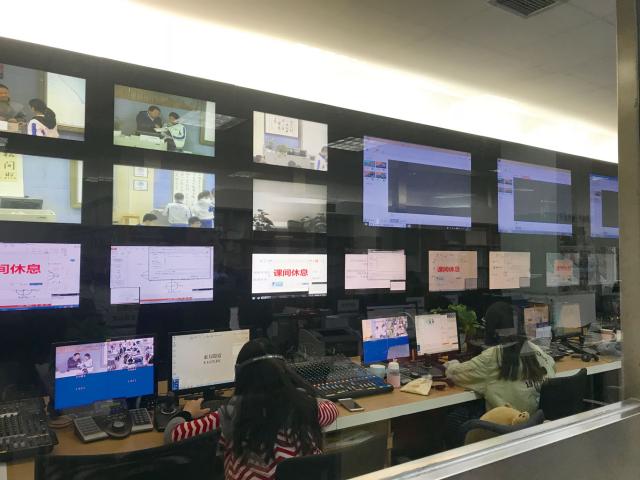

EastEdu’s staff monitors signals to more than 200 schools that take their livestreamed classes, Sichuan Province, November 5, 2018

Insurmountable Gap

Li Yifei, a lecturer at Beijing Normal University who works with a rural education charity, disapproved of how remote classes were being touted as “fate-changing.” “Fate is full of uncertainties, and it definitely does not end with getting into university,” he said.

An anonymous student in Sichuan agreed. He dropped out of livestreamed classes after losing hope of ever catching up. “Our teachers would say that the classes put us on the same footing as students from Chengdu No.7 High School. But it turned out that the gap is insurmountable and far beyond exam scores,” he told NewsChina.

According to Fang Jin, deputy secretary-general of the China Development Research Foundation, urban-rural inequality in education becomes apparent in the earliest stages of child development.

For example, while urban parents are busy with arranging early childhood education, those in rural areas are not even aware it exists. Since 2007, Fang’s foundation has been training parents of children between six and 36 months in early family education. As a result, in an impoverished county in western Gansu Province, follow-up studies showed that average IQs among children of parents who had received the training increased by 51.4 percent over two years.

“The gap between rural and urban areas lies in the imbalanced distribution of public resources and services. That is why the [2018] National Economic Conference pledged to increase preschool and vocational education for rural children. But I think this should come with the breaking down of hukou (permanent residential registration) barriers to resource distribution,” Fang said.

“Education is the only way for underprivileged children to enjoy equal rights and opportunities. Different children may choose different roads, but we must ensure that the choices they’ve made are those of free will rather than pure survival. This is the true significance of education,” he added.

Old Version

Old Version